Lost or Found [Mason Street Literary Magazine, March 8, 2022]

The following is a portion of the correspondence between Mara Ahmed and Claudia Pretelin. Ahmed is an interdisciplinary artist and activist filmmaker based on Long Island, New York. Claudia is an art historian, independent researcher, and arts administrator based in Los Angeles, California. The two women collaborated on several projects, starting with Current Seen, Rochester’s biennial for contemporary art. In 2020, Claudia interviewed Ahmed for Instruments of Memory, a site she curates and which documents conversations with women in the arts. As a response, Ahmed decided to interview Pretelin about her work, but in the form of a dialogue about art, memory, language, and becoming. They hope to continue this conversation over the years and capture the continuing shifts in their lives and work. Their correspondence is a collage of text, images, and references both literary and cultural. It is intimate and global, straddling distances between Mexico, Pakistan, Belgium and the US.

August 5, 2020

Dear Claudia,

Love the interview you did with me. Thank you for your exquisite attention to detail and the care with which you curated my work. I was thinking, in a reversal of the process, perhaps I could do an interview with you about your life and work. I know your bio is already included in Instruments of Memory, but we could have a conversation about art, memory, what inspires you, and what shaped the direction of your life. How is your family in Mexico? How has the pandemic affected life there?

Thinking of you and sending hugs,

Mara

August 5, 2020

Dear Mara,

Thank you for your kind message.

I’m working on having the interviews translated in Spanish. It will take some time, but I hope to have everything ready by the end of this year.

Regarding your proposal, I would love to do an interview with you about my work. In fact, it would be an honor.

My family in Mexico is doing well, thanks for asking. Miss my Dad and hope I will get to see him again soon.

Lots of hugs and love back at you!

Talk soon.

August 8, 2020

My Dearest Claudia,

Glad to know your family is doing well. Are there any flights to Mexico at the moment? International travel is cumbersome right now. My parents are in Lahore and I’m not sure when they will be able to fly here.

I’m excited to interview you. Am thinking about something different – more of a back-and-forth about art and activism but also about being women, immigrants, American, and living in multiple languages. What do you think?

Or we could each choose art/photographs/films that inspire us, explain what they mean to us, and how we interpret them. It could become a photo essay.

August 9, 2020

I love all your ideas.

Here’s something to start with:

I saw this image by Mary Ellen Mark the other day and the quote really resonated with me. “In a portrait you always leave a part of yourself behind.” I guess one can think about this in many different ways but it made me think of every time I’ve moved to a new place. I left a part of myself in that place.

Do you feel the same way?

[Photo] In 1998, while I was in college, I went to see the exhibition “Mary Ellen Mark: 25 years” at the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City. I was so impressed by her work that I remember deciding at that moment that I wanted to study and write about photography. Two years later, after I graduated from college, I got my first job as a curatorial assistant in the department of photography at the same museum. Someone took this photo of me while at work in 2001. I overlaid a picture of birds I took during a trip to India in 2017. Both Graciela Iturbide and Mary Ellen Mark visited India and captured this country in poetic and evocative photographic images that have inspired me. This is my very humble way of honoring their work and inspiration.

The first time I really connected with photography was during an exhibition by Mary Ellen Mark in Mexico City in 1998. Years later I was lucky to meet her in person during one of Graciela Iturbide’s exhibitions in New York City. Mary Ellen was so generous with her time. In my memory, we talked for what felt like a long time, but in reality it was no more than 15 or 20 minutes. I remember that talking to her made me feel like she was really seeing me. What a strange feeling! I always wonder if all her photographic subjects felt the same way.

August 11, 2020

Dearest Claudia

The photograph you sent me and the questions you posed about both time and place, sparked countless thoughts in my mind.

The idea of leaving something of ourselves in places we visit or reside in, reminded me of the opening lines in A Thin Wall, my documentary film about the 1947 partition of India:

Places inhabit us, as much as we inhabit them. They form the myths and lore of who we are. Landscapes with edges softened by memory, imagined homes, burnished light – dream-soaked remnants of loves and lives, stubborn in how they bind us to the past even as we are propelled into the future.

It’s as if there was some physical exchange, a sticky mixing together of people and places.

In A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit talks about how places “become the tangible landscape of memory,” how places make us, and in some way we become them. “They are what you can possess and in the end what possesses you.”

I want to know about the cities in Mexico that made you, that possess you. Could you share pictures and tell me more about the sticky interchange or “becoming” that happened between you and those places?

I was also interested in the idea of time that you hinted at: how time is relative, not absolute. After all, the linearity of time, its constant scientific calculation, and oppressive dominance represent a Western capitalist imperative. Other cultures understand and experience time quite differently. For example, the Yoruba of Nigeria perceive time as being circular. There are no clear-cut partitions between the past, present and future. They are woven together so intimately that eternity is no longer remote.

Artist Yetunde Olagbaju examines such notions of time in their video, i gave myself space to go back…pt II.

They explain:

My artwork explores, exists within, and expands on the idea of nonlinear time. I’m Nigerian, Yoruba, and have always been connected to the idea that we are in constant conversation with our past, present, and future selves. To go even further, I also believe we are in constant interaction with other people’s past,present and future selves. Ultimately what that ends up translating to, art wise, is a sort of “emotional excavation” practice: learning about time travel, and sorting through how we, as human beings, orient ourselves through our emotional and physical landscapes—our internal and external worlds. At the end of the day I care about being able to create other worlds where we can communicate with our past, present, and future selves, and about building worlds in which we can heal those aspects of ourselves.

[Photo] An accordion of time or how the past enfolds the present: With my mother as a young woman on the left and with both my parents celebrating my first birthday on the right

What do you think about that?

Love,

Mara

October 28, 2020

Dearest Mara,

Please accept my apologies for my VERY late response to one of your questions. It’s amazing how time escapes us.

I don’t have photographs of everything but found some memories that made me smile. In 1985, Mexico City, my hometown, experienced a major earthquake that killed thousands of people and caused serious damage to the city. This was my first encounter with physical and emotional displacement as the home where we used to live with my grandparents and my aunt’s family was one of the ones damaged by this event.

[Photo] In 1985 my parents and I were forced to leave our home because of an earthquake. Our house (seen here in the middle) was damaged and became a hazard to live in.

Soon after the earthquake, my parents and I moved to a new home on the outskirts of the city where we became somewhat isolated from most of our family and friends. Growing up as an only child with both parents working full-time jobs, the period from elementary to middle school became a period of major introspection for me. The time I spent at home by myself, I would play records from my father’s collection. I remember an LP by American singer Eydie Gormé singing in Spanish with a Mexican guitar trio, a record that I played so many times that I believe I ruined it. I would spend a lot of time reading encyclopedias trying to memorize historical events, for no particular reason. I loved one in particular. A series of books illustrated by the Casasola Brothers, photographers who documented the Mexican Revolution.

I didn’t fully experience Mexico City again until I went to high school and was allowed to commute alone, taking the new subway line that connected the suburbs with the city. That’s when I truly got to know the city. At first it felt foreign to me as I lived in my own inner world, created to compensate for the friends I would only meet in school. I discovered that museums were free to visitors. I attended public music events and plays held at major art schools, and spent hours in libraries, bookstores, and flea markets. I became a devoted visitor to movie theatres. Mexico City and its many cultural offerings made me fall in love with the arts, with film, with music, and the beauty of those who dedicate their lives to creating such unique worlds.

In my late twenties I traveled to Monterrey, the capital of the State of Nuevo León, 200 km south of the border with the U.S. Without a specific plan to live there, on the third day of my arrival I was offered a job in a private school as an art teacher. I ended up staying for 3 years. Monterrey allowed me to become independent from family, particularly from my father’s strict views on life. It opened new worlds and gave me a better understanding of the social inequities in my country. I lived in San Pedro Garza García, a city municipality known as the most affluent neighborhood in Latin America. During the week I taught art to privileged kids, and over weekends I would travel to small towns where most men had migrated to the U.S. and left their families behind in desolate, low-income neighborhoods.

[Photo] I documented images of my students living in underprivileged communities. I often think about them. During one class, I showed them Modern Times with Charlie Chaplin. I remember how much they enjoyed it. When I moved out of the state and back to Mexico City, Nuevo Leon was entering a dark period of violence, drug wars and militarization

Every Saturday I would travel two hours to teach kids of different ages how to make movies, how to take photographs, and how to create their own interior worlds to cope with the realities of life. This was an extremely rewarding time in my professional life and I remember my students fondly. I stayed in touchwith some of them. I met some of my closest friends in Monterrey and, as has happened many times in my life, I thought this would be the place where I would put down roots.

However, life changed and I decided to go back to Mexico City to apply to grad school. Soon after my move, drug violence and organized crime took over Monterrey, the same city described years before as one of the safest cities in Latin America. I remember seeing images on television of dead bodies found hanging with narco messages in the neighborhood where I first lived and reading about gunmen opening fire on the bar where I used to meet friends every weekend. All of it a consequence of the failed strategy of declaring war on the country’s drug cartels by then president of Mexico, Felipe Calderón.

After I left Monterrey, I went back often to visit friends. But my main goal was applying to grad school and working with Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide, my mentor and friend. In 2008 I got accepted into the National Autonomous University of Mexico, one of the top public universities in Latin American. I was back in school for a degree in Art History while working for my favorite artist. It was a dream come true.

[Photo] Photo of me with Graciela Iturbide in her home studio, Mexico City, 2012

March 25, 2021

Dearest Claudia

It’s been a while. When I got your response, I was in the middle of organizing, editing, sound engineering and uploading The Warp & Weft audio archive, meant to preserve stories from 2020, the year of the pandemic. It got intense as I was doing a lot of the work on my own and corresponding/working withmore than 50 people simultaneously. Now that the archived stories are being released weekly, I can sit back and enjoy them all over again.

Thank you for the beautiful plates you sent me. That they traveled with you from Mexico to Rochester, then on to Los Angeles, and are now safe with me on Long Island, is something incredibly special. They remind me of the earthenware pots I got from Lahore called handis. I kept them in our home for years but when we moved to Long Island in early 2020, and needed to downsize, I gave them away. These plates, made of the same earthen material, painted sparsely and elegantly, remind me of the similarities between our cultures and make me feel less bereft.

[Photo] A Pakistani handi and Mexican plates

Thank you too for your email and the wonderful journey through Mexico, from Mexico City to Monterrey. You are lucky to have taught in Mexico and to have experienced the unevenness of its social fabric firsthand, through your students. The sea change you describe on account of the war on drugs is something I understand viscerally. This is what the war on terror did to Pakistan – incomprehensible, surreal violence that disrupts a country’s sense of normalcy. I feel strongly that these wars are activated from the outside. This is why they explode onto the scene in unexpected, grotesque ways and seep into people’s collective psyche.

A lot has happened in the world since we last wrote to each other. In the world and in our personal lives. I know that you lost your dear father earlier this year. I am so sorry for your loss, dear Claudia. It feels like he was a towering presence in your life. It’s an irreplaceable loss. Although both my parents are Pakistani, my mother’s family is from Gurgaon, near Delhi, and my dad’s family is from central Punjab (which became part of Pakistan). My mother’s family is Urdu-speaking and Sunni Muslim. My father’s family is Punjabi-speaking and Shia. The contrast between their cultures and traditions couldn’t be starker. Yet they met in college, fell in love, and married in spite of strong resistance from both families. These divisions are at the core of who I am. Perhaps this is why I look for borderlands, amorphous spaces where contradictions and hybridity can thrive.

[Photo] My parents, Nilofar Rashid and Saleem Murtza, before they got married

From my mother, I got a love of language and literature, and the drive to work hard and take chances, so I can learn and better myself. From my dad, I got a love of travel, and an innate need to mix up genres, disciplines, class hierarchies, and life choices. My dad reads Sufi poets like Baba Bulleh Shah, but also loves T.S. Eliot. Growing up I remember how he played qawwali and hardcore Indian classical music in our house, but also enjoyed Jagjit Singh, Carlos Santana, and Mozart.

Tell me about your parents and how their loves, beliefs, and desires have formed you?

After asking you about the places that have marked you, I asked myself the same question. Although I was born in Lahore, I was quite young when we moved to Brussels. The first place that shaped me was Woluwé-Saint-Lambert, a verdant, mostly French-speaking, residential municipality in the capital region. We lived in a high-rise, part of a community of apartment buildings that surrounded a manicured, parklike central area with abundant trees and grass. My sisters and I walked to school every day, only having to cross one small road. In the summertime, we would roller skate outside until 10:00 p.m., when the sun would finally set. We would get scolded for staying out too late but always had the excuse that we couldn’t tell what time it was. The lingering sunlight played tricks on us. We lived on Avenue de la Charmille.

[Photo] My family in Brussels, in the early years. I am the eldest child, fourth from the left

In some ways I felt completely at home, knowing the lay of the land, excelling in school, and dreaming of becoming a French writer one day. But in other ways, I belonged to a subculture – a set of ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and religious idiosyncrasies that were only legible to my family. We weren’t close to other Pakistani kids from the Embassy and so we learned to navigate a sea of whiteness. My self-awareness was bifurcated into deep self-knowledge, inaccessible to others for the most part, and a constant reading of how the white majority was seeing/reacting to me as the little brown girl from an exotic country. Things changed when we moved to Islamabad, but I kept feeling like an outsider in other ways.

[Photo] I finished high school in Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital, then went to a brand-new city for college. Karachi is the largest city in Pakistan, a commercial hub and home to one of the most important seaports in South Asia. It’s cosmopolitan and diverse, with almost double the population of New York City. The political situation was volatile when I moved there in the late 1980s. Curfews were enforced regularly. This is me in Karachi in the 1990s, after I graduated from the Institute of Business Administration. I was working for Société Générale at the time. Less than a year later, I got married and moved to the U.S. (Photograph by Umar Ahsan Khan)

I look forward to continuing our conversation and building our stories brick by brick, email by email.

Inshallah.

Lots of love and hugs to you my dear friend,

Mara

June 18, 2021

Dear Mara,

My mother used to tell everyone a story about me when I was a child. Both my parents had full time jobs, leaving them no choice but to drop me off at a childcare center while they would be at work. One day, a four-year-old me, found a way to sneak out of the childcare facility and follow one of my favorite caregivers. She didn’t notice me. I kept wandering on my own, unattended, until a woman saw me standing all alone and stopped to help. Coincidentally, she was on her way to a doctor’s appointment at the health clinic where my Mom worked. When we arrived at the clinic, one of the staff members recognized me and after questioning the woman I was with, they called my mother. She couldn’t believe her luck and the concurrence of events that rescued me that day.

[Photo] The meaning of Perderse. Claudia Pretelin’s portrait overlaid with a map of Mexico City from 1930

I often think about this story and all the possible scenarios that could have happened. I have no real memory of it – I don’t recall any fear – and I always wonder if at that age I had already developed a mental map that allowed me to navigate close to my mother’s workplace.

I also think about our experiences with loss. What does it mean to be lost, to get lost, to lose someone?

My mother died on November 23, 2009, she was 59 years old.

My father died on January 11, 2021, he was 97 years old.

When I was born my mother was 28 years old.

When I was born my father was 55 years old.

This is a fragment of “their song,” Candilejas by José Augusto:

Tú llegaste a mí cuando me voy | You came to me as I was leaving

Eres luz de abril, yo tarde gris | You are April light, I gray evening

Eres juventud, amor, calor, fulgor de sol | You are youth, love, warmth, sunshine

Trajiste a mí tu juventud cuando me voy | You brought youth to me as I was leaving

[Photo] With my family, Mexico, ca. 1981. Polaroid print

You’ve asked me to tell you about my parents and how they formed me.

In their own way, they created an environment that allowed me to find answers for myself and to develop my own sense of responsibility. Although my father wanted me to become a doctor, and it took him some time to understand how it’s possible to make a living from studying art, I know that he was proud of me. I don’t recall any conversations with my mother about what kind of expectations she had. I do remember that even when she disagreed with me, she was always supportive and happy to help me reach my goals.

From my father I learned to love films, from my mother I learned to love literature, art, and museums.

However, the best lesson I learned from them is that parents are individuals – people with their own loves, beliefs, and desires.

How have you experienced loss? Could you trace a map of these memories?

June 20, 2021

My dearest Claudia

Thank you for sharing these moving and precious memories of your parents. I know it wasn’t easy. I wish I could hug you.

Your story of being lost and found at age 4, reminded me of how I would constantly escape from home as a child. I was once found roaming down the street, in Lahore, visiting neighbors and having a good chat with them (at the age of 5), before that I left the house and followed the milkman’s daughter to see where she lived, and earlier, in Murree, I followed an older girl into the fields to pick some flowers for my mom. It came to a point where my mother threw up her hands and handed me over to my father. In Pakistan, during the summertime, afternoons are unbearably hot and siestas necessary. I remember, as a wee child, how my dad would encircle me with his leg when we slept during the day, too afraid to let go and allow me to break free.

It’s amazing that we were both escape artists!

The Spanish word perderse (perdre in French) sounds like the Urdu word pardes which means abroad, away, elsewhere, overseas, traveling in foreign lands. Could there be a connection?

As immigrants to foreign lands, are we permanently lost?

“What does it mean to be lost, to get lost, to lose someone?”

Such poetic words. They remind me once again of Rebecca Solnit’s book:

To lose yourself: a voluptuous surrender, lost in your arms, lost to the world, utterly immersed in what is present so that its surroundings fade away. In [Walter] Benjamin’s terms, to be lost is to be fully present, and to be fully present is to be capable of being in uncertainty and mystery.

When I read your words, the first image that flashed through my mind was a beach, where frothing waves erase writing in the sand. I heard Blythe Danner’s voice read one of my favorite poems, One Art by Elizabeth Bishop. “The art of losing isn’t hard to master…”

I have been lucky so far. I have not lost anyone in my immediate family, although I have lost most of my aunts and uncles – my parents’ siblings. Living in the U.S., away from extended family, it is difficult to mourn loved ones back in Pakistan and make such losses real. It’s like being in a state of suspension – unmoored and unsubstantial.

Like you, I have lost cities, continents, friends, homes, communities, and languages. Always there is this ache in one’s heart. A sorrowful mourning.

Recently, I lost Rochester, New York, a city I knew and loved for 18 years. A city where my kids grew up and where I became an activist filmmaker.

[Photo] Starting from the top left (clockwise): Farm on Mill Road in Pittsford (near our house), my husband and I at a wedding reception, our kitchen where I had painted our cabinets blue as an homage to Sidi Bou Said (Tunisia), at the Memorial Art Gallery after visiting Lessons of the Hour, “a meditation on the life, words, and actions of Frederick Douglass” by Isaac Julien (Photograph by Sarita Arden)

I also lost a puppy in Rochester. She came to us when she was a baby, just a few months old, and left us before we moved to Long Island. She is lodged into our hearts, humaray dil ka tukrha. She gave us 16 years enriched by her sweet, endearing presence. Our unforgettable Phoebe.

[Photo] Phoebe at home in Pittsford

In Our Experience of Grief is Unique as a Fingerprint, David Kessler writes:

Every loss has meaning, and all losses are to be grieved—and witnessed. I have a rule on pet loss. “If the love is real, the grief is real.” The grief that comes with loss is how we experience the depths of our love, and love takes many forms in this life.

Just today my daughter told me she had dreamed of Phoebe, how she looked young and full of life, and had come back to us.

Another poem I love is Memory at Last by Polish poet Wis?awa Szymborska (translated into English by Magnus J. Krynski and Robert A. Maguire). It starts with:

Memory at last has what it sought.

My mother has been found, my father glimpsed.

I dreamed up for them a table, two chairs. They sat down.

Once more they seemed close, and once more living for me.

With the lamps of their two faces, at twilight,

they suddenly gleamed as if for Rembrandt.

I wish such a luminous reunion for you, dear Claudia.

Love and hugs,

Mara

Jun 29, 2021

Dear Mara,

After rereading our stories, I am wondering whether we lost Rochester or escaped from it!

When I moved 2,601.5 miles away from Rochester to Los Angeles, I felt lost again. Lost like the day I was found wandering the streets of Mexico City in 1981. After almost three years of living in Rochester, experiencing its unique history, its Genesee River, its architecture and poetic industrial ruins still standing at Kodak Park, I was once again unsettled – in need of a new place to call home.

Lately, I find myself reading books wherein the authors explore different notions of home. I didn’t set out to look for the meaning of this word/concept/construction. Or did I?

“When the house fell down, it can be said, something in me opened up. Cracks help a house resolve internally its pressures and stresses, my engineer friend had said. Houses provide a frame that bears us up. Without that physical structure, we are the house that bears itself up. I was now the house.” ? Sarah M. Broom, The Yellow House

“Not a flat. Not an apartment in back. Not a man’s house. Not a daddy’s. A house all my own. With my porch and my pillow, my pretty purple petunias. My book and my stories. My two shoes waiting beside the bed.

Nobody to shake a stick at. Nobody’s garbage to pick up after. Only a house quiet as snow, a space for myself to go, clean as paper before the poem.” ? Sandra Cisneros, A House of My Own in The House on Mango Street

“Perhaps home is not a place but simply an irrevocable condition.” ? James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room

[Photo] Carretera 61, de Clarksdale, Mississippi a Memphis, Tennessee (Highway 61, from Clarksdale, Mississippi to Memphis, Tennessee), 1997

This is one of my favorite photographs by Graciela Iturbide. It’s a found structure. Ruins that belonged to someone. Remnants of something that once existed. Overtaken by nature.

Now I realize that I didn’t move away from Rochester, or Mexico City, or Monterrey. We are still miles apart, but I carry with me the memories I made and the people I met – including you, my dear friend Mara. Whether we lost or escaped our little Western New York refuge, those memories we carry with us are home. A home built in collaboration, in mutual support, in partnership, and complicity. A home where other women, other voices, other thoughts are invited to co-exist. Thanks for having this conversation with me, for seeing me, for being part of my home.

With love,

Claudia

Exterminate All the Brutes: a critique [Mondoweiss, May 21, 2021]

As an activist filmmaker who has been making documentaries for almost two decades and someone who loved “I Am Not Your Negro,” I couldn’t wait to watch Raoul Peck’s four-part docuseries “Exterminate All the Brutes.” Rumor had it that Peck got carte blanche from HBO to bring his vision to the screen, and I was duly intrigued.

The scope of the film is dizzying. It travels through time and space and aspires to distill 600 years of human history. It engages with the work of luminaries such as the Haitian anthropologist and scholar Michel-Rolph Trouillot and American historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz who wrote the seminal “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States.” Their oeuvre is indispensable for a clear-sighted, step-by-step unpacking of European colonialism, genocide, and hegemonic epistemological systems. I am less familiar with Swedish author Sven Lindqvist’s work, but “Exterminate All the Brutes” is partly inspired by his book of the same name.

The title is taken from Joseph Conrad’s novella, “Heart of Darkness,” which is used as a framing device throughout the documentary. I wish Peck had used Trouillot or Dunbar-Ortiz’s work instead, as an analytical lens focused on the entire project. W.E.B. DuBois could have been a gripping intellectual anchor as well. If he was looking for a literary point of reference, Peck could have used Aime Cesaire’s anti-colonial poetry (André Breton described “Cahier d’un Retour au Pays Natal” as the “greatest lyrical monument of our time”) or the writings of celebrated Black and brown poets and novelists.

I know that Chinua Achebe’s critique of “Heart of Darkness” has been challenged since it was first published in the 1970s, but I tend to agree with him when he writes:

Heart of Darkness projects the image of Africa as “the other world,” the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality.

Later in the article, Achebe quotes directly from Conrad’s book:

We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there—there you could look at a thing monstrous and free. It was unearthly, and the men were—No, they were not inhuman. Well, you know, that was the worst of it—this suspicion of their not being inhuman. It would come slowly to one. They howled and leaped, and spun, and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity—like yours—the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar. Ugly. Yes, it was ugly enough; but if you were man enough you would admit to yourself that there was in you just the faintest trace of a response to the terrible frankness of that noise, a dim suspicion of there being a meaning in it which you—you so remote from the night of first ages—could comprehend.

For a documentary that sets out to expose and catalog colonialism and white supremacy, it’s ironic that it relies on a white man’s opus to shape the very language of that critique.

What powerful beauty could have emerged from Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry, born of trauma and displacement, had it been used to underline a study of colonial violence. Darwish, the Palestinian poet who made language “home and self” because “it is outside of place and time, because with it, Palestinians ‘carried the place . . . carried the time’.”

The Holocaust is central to Peck’s thesis, and we return to it throughout the miniseries. It ties in with Cedric Robinson’s characterization of “racial capitalism” and his assertion that Europe’s earliest racialized subjects were the Irish, Jews, Roma and Slavic people.

Peck mentions Aime Cesaire’s dissection of Nazism, but I wish he had gone further and quoted these trenchant lines:

Yes, it would be worthwhile to study clinically, in detail, the steps taken by Hitler and Hitlerism and to reveal to the very distinguished, very humanistic, very Christian bourgeois of the twentieth century that without his being aware of it, he has a Hitler inside him, that Hitler inhabits him, that Hitler is his demon, that if he rails against him, he is being inconsistent and that, at bottom, what he cannot forgive Hitler for is not crime in itself, the crime against man, it is not the humiliation of man as such, it is the crime against the white man, the humiliation of the white man, and the fact that he applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the coolies of India, and the blacks of Africa.

I longed to hear about Negritude and the names of those who illuminate and guide our work in anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and anti-colonial movements: Franz Fanon, Edward Said, Malcolm X, Sylvia Wynter, Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Eduardo Galeano, Amílcar Cabral, Walter Rodney, Édouard Glissant, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and many more. But they remained silent for the most part. I understand that one film cannot be everything to everyone, but this was a four-part docuseries with a stellar budget.

As I was watching the last episode, it struck me that Peck had not so much as mentioned Palestine. A bit bizarre, since he examines settler colonialism in the Americas via Dunbar-Ortiz’s work.

And then he did. He mentioned an 18-year-old Palestinian girl who detonated herself in a Tel Aviv discotheque. Peck wonders, with some sympathy, about his own daughter and asks himself what would push her to commit such a horrific act. No other context is provided. Just a random suicide bombing. He concludes weightily, “Yes, it’s complicated.”

For someone unmasking white supremacy, that’s a shameful, cowardly, and ignorant conclusion. He co-opts one of the most hackneyed Zionist arguments against Palestinian liberation: it’s complicated.

This indefensible lapse brought my own assessment of the series into focus. Although it’s being sold as a “miracle for existing” by the filmmaker himself and mainstream media, Peck’s critique of white supremacy is articulated within the safe limits of Western liberalism. There is nothing here which is abrasive, taboo, or explicitly supportive of ongoing struggles and movements for justice.

As a filmmaker, I was dismayed by the heavy reliance on re-enactments, a cop-out available to high-budget films. Some of the fictional episodes Peck directs seem odd and disconnected. They take away from themes and storylines that don’t require any embellishment or fake drama. They squander precious time.

The fact that Peck narrates the entire four hours of the film, in a highly controlled voiceover, becomes exhausting, oppressive. He elects not to use talking heads but voices other than his would have added nuance, texture and movement to an airtight structure with no room to breathe.

Although one can take ample artistic license with documentary filmmaking, it remains an effective medium for telling stories, especially those that are pushed to the periphery and marginalized. It can lift voices missing from the dominant discourse because they don’t fit in or are not deemed valuable. Peck’s film does not take political risks or create disturbances by amplifying radical ideas. What could be a better subversion of the “bundles of silences” Trouillot wrote about, than a discussion on Palestine, a word so savagely censored that its existence is often called into question.

In spite of its vast sweep, Peck’s documentary doesn’t connect the past to the present or future. It doesn’t create compelling points of intersection and solidarity by arranging the material in new and provocative ways. Peck could have looked at the work of countless scholars, activists and public intellectuals who do just that: Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Nick Estes, Noura Erakat, Ella Shohat, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, Hafsa Kanjwal, Robin D.G. Kelley, Harsha Walia, Pankaj Mishra, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Angela Davis, Françoise Vergès, Cornel West, and numerous others.

No, Palestine is not complicated, Mr. Peck. It’s settler colonialism unfolding “live” before our eyes. As the Nakba continues in 2021, with full on ethnic cleansing in Sheikh Jarrah and war crimes in Gaza, it’s more egregious than ever to hide behind evasive language or recycled Zionist tropes.

Peck’s work is frequently praised for its intellectual rigor. “Exterminate All the Brutes” is an awe-inspiring cultural, literary, historical, political and geographic smorgasbord. It is disorienting and overwhelming. But to what end? It succeeds in collating a massive amount of information, but Peck’s compendium of darkness fails to synthesize, to metamorphose into something forceful and forward-looking, something that cuts to the bone and renders us breathless. In other words, the film fails to puncture and expand the limits of the liberal imaginary. What a missed opportunity.

Link here.

Decolonizing Art for Art’s Sake [The Markaz Review, March 1, 2021]

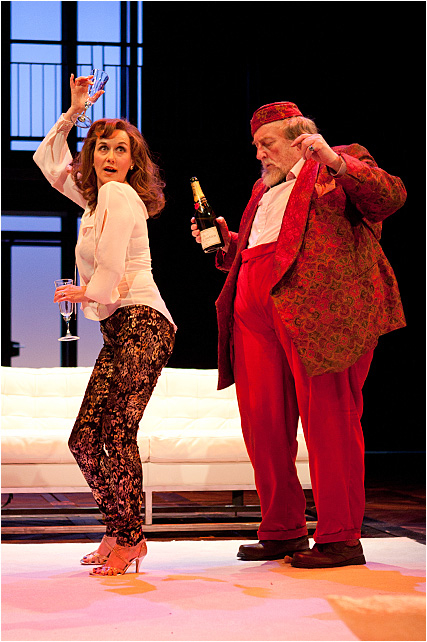

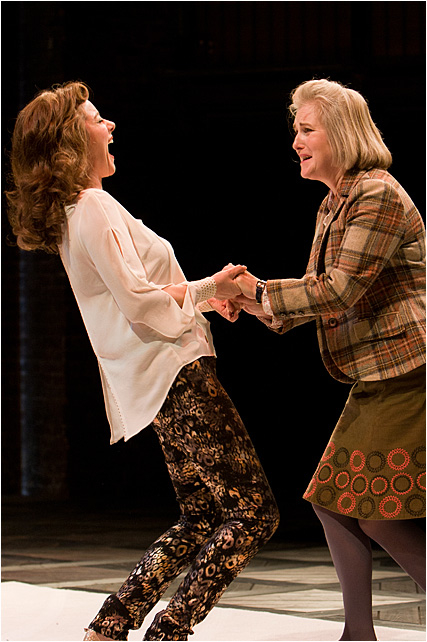

I recently came across an astonishing production of Les Indes Galantes, an 18th century opéra-ballet by Jean-Philippe Rameau, choreographed by Bintou Dembélé for L’Opéra Bastille in Paris.

Opéra-ballet is French Baroque lyric theatre or a loose blend of narrative, singing, and over-the-top dance numbers. Les Indes Galantes (The Amorous Indies) premiered at the Paris Opéra in 1735. Such hybrid works being all the rage in those days, it was performed more than 60 times in its first two years. It recounts four separate love stories, each set in an exotic locale: a Turkish pasha on an island in the Indian Ocean; a love triangle in Peru involving Spaniards and Incas; love between slave owners and slaves in Persia; and finally the fourth and final act, Les Sauvages, which takes place in North America. European enlightenment, with its foundational construct of otherness, needed to venture beyond its frontiers through imperial conquest and missionary zeal. Its violence and domination were justified by the production of Orientalist stereotypes and the enforcement of racial, cultural and religious taxonomies. The provenance of Les Indes Galantes is, therefore, grounded in racism and French colonial hubris.

Bintou Dembélé, born of Senegalese parents in the Parisian banlieues, is considered a Hip Hop pioneer in France. In her Paris Opera debut in 2019, she set out to subvert the colonial ideology of Rameau’s work by using street dance such as krump, waacking and voguing. She sees dance as “des gestes marrons” that honor the memory of slaves, marronage signifying resistance and escape from plantations, and the constitution of new communities on the outskirts of slave systems. How do these breakouts and rebellions manifest themselves in movement? For Dembélé, it’s through canny evasion and dodging, so that one can remain standing. It’s continuing to groove and take up space in spite of oppression, slavery, police brutality, colonialism and invisibility.

The clip I saw online was choreographed to “The Dance of the Peace Pipe” from Rameau’s fourth act.

The music is vigorous, almost heroic, and the dancers, mostly people of color, seem conjoined—a living, breathing human organism. At the same time, Dembélé gave the dancers free rein to perform their solos with unrestrained brilliance and emotion. They riff off of one another, moving in and out of the periphery and onto center stage. It’s a heaving mass of humanity at once collective and individual, responding to all of its diverse, composite parts. One can feel the waves of passion and resolve throbbing in its aggregate body. It’s something beautiful and fortifying that one connects with viscerally. I felt the jolt of it through my computer screen.

Surprisingly, stunning art like this doesn’t always find support. Dembélé is the first Black woman choreographer to be engaged by the Paris Opera, in its 350-year history, yet the company’s promotional materials omitted this important fact.

In an interview with Jannie McInnes, for The September Issues, Bintou Dembélé explained:

“In France, the word ‘race’ was removed from the constitution in 2018. There is something ambiguous about this decision: while its intention is to discard a historical and biological imaginary captured by this word, it also expresses a type of denial, a French difficulty with reflecting on the question of skin color. Moreover, in France, those who decry the under-representation of Afro-descendants find themselves regularly reproached for being obsessed by this issue, for seeing the world exclusively through this prism—in short, for being ‘racist.’ This denial leads to invisibility for artists of color, colonized communities, and large swathes of French society. Hence the challenges we have in performing on contemporary stages and telling our stories in ways that are legible to those audiences.”

I was an immediate fan of Dembélé’s choreography and the energy she mobilized through her sharp, expressive dancers. Not having seen a performance of Les Indes Galantes prior to my introduction to this exhilarating interpretation, I wanted to learn more about what it was that Dembélé had set out to subvert. As any reasonable person living through a pandemic, I googled Rameau’s opera and came across two productions.

The first one is by Les Arts Florissants, founded and directed by William Christie. It dates back to the mid 2000s and in the fourth act, embraces 20th century stereotypes of what indigenous peoples wear and look like. Apart from dancers donning buffalo masks (possibly) and walking on all fours, there is some traditional, quintessentially North American chicken dance and valiant singing whilst smoking corncob pipes. What is less hackneyed, but equally farcical, is the inclusion of “Walk Like an Egyptian” dance moves. An homage to the 1980s?

The second version, which can be seen in full online, is a production by Les Talens Lyriques, directed by Laura Scozzi for the Opéra National de Bordeaux. It dates back to 2014. Rameau’s prologue, a discussion between god-like figures about love and its entanglements, is turned into a random romp with lots of naked people, doing little besides being naked. I guess we’re all familiar with the maxim that nudity = high art. Scozzi, an Italian choreographer, tried to modernize the opera’s exoticism by superimposing modern themes such as human trafficking, refugee hardships, violence against women, and environmental degradation.

These scenes, besides being cartoonish and slackly choreographed, are alive with France’s colonialist obsession with Islam and the veil. In order to seem just, Scozzi added blond, white women in underwear being sexually objectified and manhandled on stage. She also shows women in bright patterned burkas running around with H&M bags and cheek-kissing jauntily (in the end, capitalism will save us all). But the bus stop signage in Arabic (“in the direction of Yemen”), the oriental carpets hanging from a clothesline, the burka clad woman walking behind a man, her head bent, and the child in a sequin burka with her teddy bear being married off to an adult male are nauseating. A privileged white woman, speaking for women of color, submitting them to her Orientalist gaze, and articulating them in her own jaundiced language is nothing new. Yet it never ceases to repulse.

That this Charlie Hebdo-ish caper or the racist cartoon by Les Arts Florissants could be funded and allowed onto any stage is a marvel. Bintou Dembélé’s work is not just political subversion, it’s exceptional art, whereas these other two productions succeed rather easily in showcasing white mediocrity. This is why it bears repeating that decolonizing art/culture is not just good for politics, it also makes for unquestionably better art.

Link here.

Borders Can Be Borderlands [Mason Street, January 31, 2021]

A BORDER IS A DIVIDING LINE, A NARROW STRIP ALONG A STEEP EDGE. A BORDERLAND IS A VAGUE AND UNDETERMINED PLACE CREATED BY THE EMOTIONAL RESIDUE OF AN UNNATURAL BOUNDARY. IT IS IN A CONSTANT STATE OF TRANSITION. THE PROHIBITED AND FORBIDDEN ARE ITS INHABITANTS.

. . . GLORIA ANZALDÚA, BORDERLANDS/LA FRONTERA: THE NEW MESTIZA. SAN FRANCISCO: AUNT LUTE (1987)

It’s 1947, the end of British colonialism in South Asia. Unsurprisingly, independence is concurrent with the mutilation of land. Two nation states are created: Pakistan for Muslims, India for Hindus. No thought is given to Sikhs, Christians, Parsis, Jews, or the myriad sects and violent caste hierarchies within Hinduism and South Asian Islam. Quick lines are sketched by a British lawyer and the lives of millions thrown into a tailspin. As people begin to move across an arbitrary border, riots break out. Ethnic cleansing follows. Millions are displaced, broken, killed.

This is not that Dawn for which, ravished with freedom,

we had set out in sheer longing,

so sure that somewhere in its desert the sky harbored

a final haven for the stars, and we would find it. (1)

It’s 1947. My mother, Nilofar Rashid, is five years old, her mind like a sponge, her senses alive to the chaos around her, every scene etched into her memory, a graphic novel in bas-relief: huddled together on a rooftop as attacks on Muslim homes are underway on the street below; escaping under the cover of night with help from Hindu neighbors; hiding by the side of the road as trucks full of Sikhs chanting ominous slogans go by; living on cans of evaporated milk in ad hoc refugee camps; boarding a congested ‘special’ train to cross the line between India and Pakistan, its walls splattered with blood from previous massacres. A sigh of relief and prayers of gratitude as soon as they reach Pakistan. Then the scenes that await them: dead bodies piled up at the railway station in Lahore, the stench of industrial-strength disinfectants, houses burnt to the ground, others left with cars in their driveways and locks on their doors. A city cleaved with a butcher’s knife, still trembling, waiting for the blood to coagulate.

It’s still 1947. Refugees become eligible for the allotment of evacuee property. My grandfather, Rashid Ahmed Qureshi, receives temporary possession of a mansion recently owned by a Hindu family. As a child, my mother is entranced by its prayer room, an intimate shrine resplendent with paintings of Krishna and his Gopis. The Hindus who have fled Lahore, leaving all these beloved objects and memories behind, seem to fill the negative space wrapped around the city. The air is smeared with smoke and dread.

THEY MOVE IN COLOUR, CARRYING EVERYTHING THEY CAN. THOUGH THE EYE OF THE CENTURY SEES THEM IN BLACK AND WHITE, AS A SERIES OF STILLS IN A PHOTOGRAPHER’S PORTFOLIO. PARTITION: SOUNDS LIKE A THIN WALL MADE OF SIMPLE MATERIALS BETWEEN ROOMS THAT CAN EASILY BE TAKEN DOWN. TAKE THE WORD IN YOUR LEFT HAND AND FEEL ITS WEIGHT. IT IS NOTHING – A FEW SHEETS OF PAPER.

. . . JOHN SIDDIQUE. SIX SNAPSHOTS OF PARTITION, GRANTA MAGAZINE (OCTOBER 2010)

It used to be that borders were formed naturally, by oceans and mountains, carved out by the physical contours of the earth’s surface. There was something poetic about these landforms, extending from foothills and valleys, to plains and plateaus, all the way to seafloors. They were shaped by wind and water erosion, pushed up by the collision of tectonic plates, forged by volcanic eruptions, sandblasted and weathered over millions of years. They were substantive, grounded in history.

The borders that came out of the crumbling of empires, in the 20th century, were different. Cartographic inventions meant to divvy up world resources and power, divorced from indigenous logic or priorities. A few sheets of stolen paper.

In her book Undoing Border Imperialism (2), Harsha Walia challenges the notion of absolute, static borders by examining their elasticity. They can shift inwards to create spaces of containment and control, such as detention centers and the prison industrial complex, but they can also expand outwards to encompass black sites and colonial frontiers. Perhaps borders are systems and procedures, institutions and agents, rhetoric and symbols meant to wield power.

The confused and panicked children frantically wept for their parents, who had been separated from them at the U.S.-Mexico border under the Trump administration’s family separation policy. “Mami!” “Papa!” the children from Central America screamed, as if they knew no other words. “I don’t want them to stop my father,” one child said through tears. “I don’t want them to deport him.” Hearing the pleas that were captured on audio two years ago, a U.S. Customs and Border Patrol agent joked, “Well, we have an orchestra here. What’s missing is a conductor.” (3)

Violence tears into whatever territories or bodies are marked by borders. They delimit and police definitions of what is human or barbarous, valuable or expendable, colonizing or colonized.

“I was worried that I was going to get raped,” says artist Jackie Amézquita about crossing the U.S.-Mexico border when she was eighteen years old. In her performance piece Huellas Que Germinan (Footprints That Sprout), she walked for eight consecutive days from the U.S.-Mexico border to Los Angeles, in order to embody the hardships and dangers of her migration from Guatemala to the United States. It was an intense process whereby the physical act of walking became synched with the act of reminiscing and confronting difficult memories. Time seemed to fold over, with the past, present and future all jostling for space simultaneously. (4)

The linearity of time has its own imperious regime and hardened silos. Capitalism partitions everything.

My poems interrogate the language of power and state-sponsored language, and they explore the ways in which violence against bodies is premeditated in violence against language. (5)

In the Indian subcontinent, languages were partitioned long before the land ever was.

Back in April 1900, as Arundhati Roy has written, Sir Anthony MacDonnell, lieutenant-governor of the Provinces of Agra and Oudh, issued an order permitting the use of the Devanagari script in state courts where the Persian script had ruled heretofore. “In a matter of months,” Roy explains, “Hindi and Urdu began to be referred to as separate languages. Language mandarins on both sides stepped in to partition the waters and apportion the word-fish.”

In a bid to purify and distinguish further, Hindi became more Sanskritized and Urdu more Persianized. “But Sanskrit was the language of ritual and scripture, the language of Priests and Holy men. Its vocabulary was not exactly forged on the anvil of everyday human experience. It was not the language of mortal love, or toil, or weariness, or yearning. It was not the language of song or poetry of ordinary people… Rarely if ever has there been an example in history of an effort to deplete language rather than enrich it. It was like wanting to replace an ocean with an aquarium.” (6)

Whereas the process of scrubbing and sundering these languages has been labored and reductive, their constant engagement is what shaped the history of India. It facilitated the imbrication of social and moral codes, of political ideas and multifaceted cultures from diverse linguistic worlds.

If borders delineate zones of violence, activated by Western binarism and othering, then borderlands are in-between spaces – zones of contact that embody hybridity. Chicano/a traditions in the borderlands along the Mexican-U.S. border, exemplify mestizaje – the art of navigating multiple epistemological and philosophical systems. Gloria Anzaldúa defines mestiza consciousness as the ability to reconceptualize difference by disrupting racial, cultural, gender and class demarcations.

The work of mestiza consciousness is to break down the subject-object duality that keeps her a prisoner and to show in the flesh and through the images in her work how duality is transcended. The answer to the problem between the white race and the colored, between males and females, lies in healing the split that originates in the very foundation of our lives, our culture, our languages, our thoughts. A massive uprooting of dualistic thinking in the individual and collective consciousness is the beginning of a long struggle, but one that could, in our best hopes, bring us to the end of rape, of violence, of war. (7)

Borderlands offer connectivity. Jackie Amézquita’s art practice is grounded in this idea of cultures touching, merging, and transforming one another. Her work explores the interactivity between different ethnic groups across geographic, political, and psycho-sociological borders. Her own skin becomes a form of connective tissue between her interior and exterior worlds.

The Martinique poet and philosopher, Édouard Glissant, describes such a world as an archipelago consisting of many distinct parts, where borders become points of passage rather than obstacles to movement. Instead of a European universalism that requires homogenization and integration, Glissant proposes a ‘non-universal universalism’ which is supple enough to adapt to change. In this Tout-Monde, human differences are acknowledged all at once, and are in equal relationship with one another. It’s an open totality that requires constant negotiation, exchange, and mixing between a multitude of identities and in doing so, it produces unknowable outcomes. Unknowability, as espoused by Glissant, is a repudiation of stability and the model of airtight safety we are told to desire and strive for. His conceptualization of the manifold is a chaos world, where people learn to cope with unpredictability and become adept at withstanding tensions. (8)

It’s important to clarify that economic disparities between countries, and between people within countries, are not the colorful multiplicities Glissant speaks of. Such power imbalances do not represent atavistic identities but rather the theft and exploitation of labor and resources sustained by capitalist infrastructure, in direct contravention of Glissant’s egalitarian vision.

Nature too depends on the chaotic interface between differences, in order to achieve vitality and resilience.

[I]f there’s anything that the local earth wherever you live teaches, it’s the need for diversity, the need for the whole, weird multiplicity of shapes of life and styles of sentience—all of them shaped so differently from you and from one another—to be interacting with one another in order for the land to be strong, to be healthy, to be resilient. And so as we open our hearts and open our senses to the wider sensuous earth, I think we imbibe this deep teaching of diversity, of the need for an irreducible pluralism, and for celebrating otherness and radical alterity, radical otherness in our world, not looking to just shelter ourselves among those who think just like us or speak just like us or look just like us, but taking deep, new pleasure in otherness and strangeness. (9)

All of this is not an impossible dream. In fact, it’s happened already. Look at the subcontinent.

Just as the Sanskrit and Persianate worlds came together to create a borderless cosmopolis in South Asia, the millennia-long encounter between Hinduism and Islam also produced firmly embedded syncretism. In Pankaj Mishra’s words: “Incredibly, much of the subcontinent’s composite culture has survived both the divide-and-rule strategies of British colonialism and the rivalry between the nation-states of India and Pakistan, which has produced three major wars since 1947. This enduring pluralism is rooted in the traditional diversity of religious practice across the subcontinent marking a contrast to the more recent state-guaranteed multiculturalism of Europe and America. Here the pluralism preceded the establishment of the modern state, and it is often at odds with the state’s insistence on singular identities for its citizens.” (10)

In its solemnly wise way, history reminds us that borders can be meeting points, rather than lines of separation. Borders can be radically soft and porous, rather than festering wounds inflicted on people and land. Borders can be borderlands. We can map their dynamic potential by looking at liminal, in-between, intersectional, hybrid spaces. This is where, according to Manthia Diawara, “relation and difference link entities that need each other’s energy to exist in beauty and freedom.” (11)

This is where we thrive.

Link here.

- Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Subh-e-Azadi (August 1947), Translated from the Urdu by Agha Shahid Ali, Annual of Urdu Studies 11 (1996)

- Harsha Walia. Undoing Border Imperialism. AK Press (November 12, 2013)

- The Southern Poverty Law Center, http://www.splcenter.org (June 18, 2020)

- Andrea Alonso. This Artist Walked from Tijuana to L.A. to Make a Powerful Statement, Los Angeles Magazine (April 27, 2018) / jackieamezquita.com

- Solmaz Sharif. Look: Poems. Graywolf Press; 1st edition (July 5, 2016)

- Arundhati Roy. What is the Morally Appropriate Language in Which to Think and Write? The New Yorker (July 2018)

- Gloria Anzaldúa. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute (1987)

- Edouard Glissant. Poetics of Relation. University of Michigan Press (September 29, 1997)

- David Abram. The Ecology of Perception: An Interview with David Abram, Emergence Magazine (July 2020)

- Pankaj Mishra. Beyond Boundaries, The National (November 2009)

- Manthia Diawara. Édouard Glissant’s Worldmentality: An Introduction to One World in Relation (2009)

The Unvarnished Truth about Obama, Harris and Diversity without Accountability [The Markaz Review, Nov 27, 2020]

Obama’s new book, A Promised Land, has been making the rounds. It’s everywhere on social media, much like Michelle Obama’s Becoming was a couple of years ago. Both dust jackets glow with the same Photoshop finish, two attractive people a bit shy about the strength of their own magnetism. Smart, effortlessly debonair, moneyed. Diametrically opposed to Trump’s vulgarity, civilized in their discourse (“I felt quietly angry on his behalf. To protest a man in the final hour of his presidency seemed graceless and unnecessary,” he writes about Bush), and confident in the gushing response from their stans.

Obama, the drone president. The man who dropped 26,171 bombs his last year in the White House. Literary rock stars like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Zadie Smith fangirl over his remarkable writing and unimaginably difficult presidential decisions. The decency of his character is assured, in spite of his war crimes. He’s got a multimillion-dollar Netflix deal after all, and the power to gift us Joe Biden.

He makes us feel nostalgic for the good old days, when America was truly great. Everyone knows he killed almost 4,000 people in 542 drone strikes, deported more than 2.5 million others, and force-fed Muslim men categorized as non-human in Guantanamo. He expanded mass surveillance, sabotaged universal healthcare, built migrant cages at the border, and pretended to drink Flint water in order to lie about its safety.

He didn’t just do the broadly brutal, presidential butchery we expect from American presidents, he made it personal. He handled kill lists, droned a 16-year-old American kid in Yemen along with his 17-year-old cousin, started spanking new wars, and called the president of Yemen to halt the release of a journalist reporting on drone casualties in that country.

Yet here we are.

The boring repetition of these atrocities can be set aside easily. Pictures of dead children or their wailing mothers don’t really register if they’re not wearing the right clothes or speaking the right languages. We can say sensibly that collateral damage is a price we are willing to pay, as long as someone else is actually paying that price. Would we be equally understanding about the droning of our own children for the greater good of the world? Why is that a crazy question?

Seems graceless to bring all of this up, right after the launch of Obama’s elegant oeuvre. Accusations of crudeness remind one of Houria Boutelja’s book Whites, Jews, and Us which so offended white sensibilities. Anthropologist Nazia Kazi explicates how Boutelja “claims this crudeness as a very marker of her social position: ‘The dispossessed indigenous person is vulgar. The white dispossessor is refined.’ What are civility, vulgarity, and manners in a world shaped enduringly by the brutality of empire?” she asks.

Maybe that’s just how it is these days: everything whitewashed, packaged like an Apple product, branded like a captivatingly effete IG influencer, and placed adroitly like sponcon. It’s hard to tell the news from the ads, Hollywood films from military propaganda, or Nobel Peace Prize winners from assassination masterminds. Everything’s pulverized together into a bland paste of vacuity. Makes one hungry for guerrilla filmmaking and some raw, unvarnished truth.

• • •

As we look forward to a Kamala Harris vice presidency, pictures of her channeling Ruby Bridges and Rosa Parks have gained popular currency online. Representation continues to be a means of achieving multiculturalism, without challenging the structures it dresses up.

What about Harris’s actions? Out of the millions of undertakings she could have prioritized, as San Francisco D.A., she decided to crack down on school truancy. One of her regular shticks at speaking events was to tell the story of how she brought charges against a single mother of three, who was homeless and working two jobs. It demonstrated the tough love of her anti-truancy initiative, the fear she could instill by an artistic rendering of her badge on her letterhead. In another talk, she made fun of criminal justice reformers, mimicking their protests on stage. It’s painful to watch — her flippancy, arrogance and cluelessness.

Harris is younger than many of the men in leadership positions around her. Perhaps she will begin to align more with what’s happening in the country. But it bears repeating that representation doesn’t go very far when it’s only a symbol of individual success. Unless people of color in positions of power, challenge existing systems and try to improve the lives of the most marginalized, their “diversity” is just about optics.

In the words of Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor:

“Symbolic firsts are no substitute for substantive gains. We have been celebrating firsts for fifty years but the gains for the few almost never translate into a better life for the many… These celebrations are old and our people are dying. Enough.”

Link here.

‘Sultana’s Dream’ Project and the Disappearance of Muslim Feminisms [Countercurrents, Apr 17, 2020]

I was fascinated to learn that a new exhibit at the Memorial Art Gallery (MAG), in Rochester, New York, celebrates Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s Sultana’s Dream. For those who have not heard of this groundbreaking work, a quick Google search yields this synopsis on Wikipedia:

Sultana’s Dream is a 1905 feminist utopian story written by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, a Muslim feminist, writer and social reformer from Bengal. It was published the same year in the Madras-based English periodical The Indian Ladies Magazine. It depicts a feminist utopia (called Ladyland) in which women run everything and men are secluded, in a mirror-image of the traditional practice of purdah. The women are aided by science fiction-esque “electrical” technology which enables laborless farming and flying cars; the women scientists have discovered how to tap solar power and control the weather.

In her 2009 article in the Guardian, ‘What happened to Arab science fiction?’ Nesrine Malik cites Sultana’s Dream as an illustration of science fiction’s subversive potential:

…if there is a sense of despair and censorship, what better way to counter the former and circumvent the latter than engage in flights of fancy and imagination? To vicariously revolutionise and hope via a medium of fantasy? With Arab literature so focused on classical themes, an Orwellian allegory, for instance, would tackle the present and envision a future in a more clandestine fashion than a straightforward political attack.

Sultana’s Dream is an example of such critique. Written in 1905 by a Muslim feminist writer and social reformer who lived in British India, it is one of the earliest examples of feminist science fiction, and is a sort of gender-based Planet of the Apes where the roles are reversed and the men are locked away in a technologically advanced future.

An indictment of the purdah system, it was much more than simplistic utopian thinking but a philosophically mature vision of a world where, following defeat in a crushing war, men succumbed to isolation in exhaustion and disillusionment with a world dominated by brute male force. It was also an extension of the author’s frustration with the limitations imposed upon her by her own society.

For me personally, as a South Asian, Muslim, woman activist, Sultana’s Dream has always been a source of great pride and inspiration. Last year, I wrote about non-European, nonwhite, decolonial feminisms and the importance of reckoning with that history:

I remember when Laila Lalami came to Rochester many years ago to read from her 2005 book, ‘Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits’. I’d been a fan of her writing since her moorishgirl.com days and so I went. During the Q&A someone asked her a question about how feminism evolved in North Africa by trying to understand its ties to western feminism, because how else would Moroccan women know about their rights? Laila was visibly annoyed and had to take a sip of water before she responded. I never forgot that question – this ridiculous notion that feminism is a western idea.

I’m reading Urdu poet and writer Fahmida Riaz’s book, ‘Four Walls and a Black Veil,’ and in the foreword Aamir Hussein talks about how “poems such as ‘The Laughter of a Woman’ and ‘She is a Woman Impure’ celebrate femininity in ways that French feminist theorists such as Julia Kristeva, Helene Cixous and Luce Irigaray were to do. Just as Ismat Chughtai prefigured by several years Simone de Beauvoir’s theoretical configurations in ‘The Second Sex,’ so too Fahmida wrote fearlessly about blood, milk and the waters of birth before her western contemporaries began to formulate their theories of women’s writing as grounded in bodily experience, and most certainly before she could have been exposed to their writings.”

I read Chughtai’s seminal, semi-autobiographical Terhi Lakeer (The Crooked Line) in English, a translation by Tahira Naqvi, some years ago and was blown away by its power. In her foreword to the English translation, Naqvi writes, “it was Ismat Chughtai who, fearlessly and without reserve, initiated the practice of looking at women’s lives from a psychological standpoint. This brings me to the interesting parallels that one can see between ‘The First Phase’ in The Crooked Line and the section titled ‘The Formative Years: Childhood’ in The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir’s pioneering work on female sexuality which appeared in 1949, four years after Chughtai’s novel. As a matter of fact, there are certain portions in Chughtai’s novel that seem to be fictionalised prefigurations of Beauvoir’s description and analysis of childhood playacting and fantasy; it seems as if Chughtai and Beauvoir were drawing on a common source. In both works, feminine experience is explored from childhood through puberty and adolescence to womanhood, these being the stages in the development of a sense of self that finally results in an acceptance of sexual impulses and subsequently leads to the awareness of a sexual identity.”

And of course, we can go back to ‘Sultana’s Dream’ a feminist utopia imagined and articulated by Rokeya Hossain, a writer and social reformer from Bengal.

Rokeya Hossain was born in 1880, Ismat Chughtai in 1915, and Fahmida Riaz in 1946. All three women were Muslim and Brown (South Asian). This is just a small bit of history (literature), so much more can be found in the nonwhite, non-western world. And confining ourselves to what’s written only, is egregiously short-sighted, considering the significance of what is passed down through stories and diverse oral traditions.

Given this context, I was eager to read the description of Chitra Ganesh’s art exhibit ‘Sultana’s Dream’ at MAG. It is a collection of prints, black linocuts on tan paper, which utilize Rokeya Hossain’s text and imagery in order to engage contemporary politics.

What stunned me in the discourse I encountered online was the complete erasure of Rokeya Hossain’s identity as a Muslim woman. There is no mention of her religion, whereas the artist, Chitra Ganesh, is explicitly described as being ‘born and raised in a Hindu Indian immigrant family in Brooklyn and Queens.’

This erasure is particularly painful and symbolic at a time when Islam is strategically advertised as misogynistic and Muslim women stereotyped as submissive and in need of ‘saving.’ Invisibilizing Muslim women, especially feminist trailblazers such as Hossain, by jettisoning parts of their identities and political provenance, is not just negligent, it’s damaging.

It reminds me of how Islam is excised from Jalaluddin Muhammad Rumi’s poetry. Rumi, as he is mostly known to his American fans, is often described as the best-selling poet in the United States. His most widely read translations are produced by Coleman Barks, a Ph.D. in English literature from Chattanooga, Tennessee. Barks does not read or speak Farsi, is not familiar with Islamic literature, and owns his decision to minimize references to Islam. In her New Yorker article, ‘The Erasure of Islam from the Poetry of Rumi,’ Rozina Ali quotes Omid Safi, a professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic studies at Duke University:

Discussing these New Age “translations,” Safi said, “I see a type of ‘spiritual colonialism’ at work here: bypassing, erasing, and occupying a spiritual landscape that has been lived and breathed and internalized by Muslims from Bosnia and Istanbul to Konya and Iran to Central and South Asia.” Extracting the spiritual from the religious context has deep reverberations. Islam is regularly diagnosed as a “cancer,” including by General Michael Flynn, President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for national-security adviser, and, even today, policymakers suggest that non-Western and nonwhite groups have not contributed to civilization.

The debate about who has contributed to civilization (and therefore whose life is valuable or expendable) is equally crucial in today’s India. With mechanisms set up to strip Muslims of their Indian citizenship, the continued occupation of Kashmir, the recent anti-Muslim pogrom in Delhi instigated by Hindu nationalists, and now talk of a ‘corona jihad’ whereby the pandemic is being weaponized to stoke violence against Muslims, it is more imperative than ever to articulate and recognize the identity of Indian Muslim reformers and icons, especially fearless, radical women such as Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain.

I can only hope that MAG will heed this call for due diligence and, in fact, use this exhibit to start a conversation about Muslim feminisms. It is an area of study and activism packed with historically rich, complex, and compelling materials waiting to be explored and critically engaged with. Link here.

An Open Letter of Solidarity [Rochester Beacon, Jan 13, 2020]

The Hanukkah stabbings in December 2019 prompted us—a group of Rochester-based Muslim and Jewish activists—to unpack the attack and Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s response, by parsing the political context in which such hate crimes become possible and voicing the need for targeted communities to pull together. The beginning of the new year 2020 saw another act of violence, with President Donald Trump provoking a war with Iran and unleashing heightened Islamophobia and xenophobia in the country. An open letter of solidarity became even more important to us, especially one grounded in political analysis and a strong desire for justice and intersectional allyship. Here it is:

More than 70 years after the end of World War II and the defeat of Nazi Germany, we are seeing a resurgence in ethno-nationalism and an emboldening of white supremacy. In the past year, bigotry-fueled violence has targeted synagogues, mosques, Black churches, and other centers of religious and cultural life for frontline communities.

As the world becomes more inequitable and precarious, with climate change threatening our very survival, high-profile figures in positions of political and economic power (within the U.S. and around the world) continue to use hateful rhetoric and the scapegoating of marginalized groups and minorities to distract from the failures of capitalism.

At this time of fear-based politics and endless wars, when the far right is preparing to defend itself against “white genocide,” it is critical that we remain steadfast in our solidarity with all communities under threat and not fall prey to tactics that aim to divide and conquer. It is the only way to challenge the divisions rooted in racial capitalism, which are deployed both locally and globally.

One of the pernicious characteristics of white supremacy is that it can readjust racial hierarchies to fit the prevailing interests of the ruling class. For example, the last century has witnessed a number of European ethnic minorities gain access to American whiteness. Although discrimination against Jewish people is nowhere near the levels it was in the 1940s, when ships of European Jews fleeing Nazi execution were turned back by the U.S. government, or in the 1960s when Jews were barred from certain jobs and neighborhoods here in Rochester, the acceptance of white Jews into white America continues to be challenged by recent events. Needless to say, in a country defined by racism, anti-blackness and anti-indigeneity, Jews of color were never given such access in the first place. With the election of Donald Trump and the increased usage of scapegoating and pitting of oppressed communities against one another, anti-Semitism is once again on the rise and the definitions of whiteness and citizenship are shifting.

The othering of Muslims has always been closely tied to their racialization. Although the demarcation between East and West is arbitrary, Islam is consistently portrayed as exotic and unchanging by European Orientalists. Muslims are constructed as a race diametrically opposed to the West and its genius for progress. This is why, in spite of the fact that Islam’s roots in this country go back to colonial and antebellum America, it is still considered foreign and incompatible with U.S. values.

U.S. foreign policy and decades-long wars on Muslim-majority countries have further devalued Muslim lives. The recent escalation of violence between the U.S. and Iran is a good example of how calls to war are invariably followed by a spike in xenophobia and Islamophobia.

In his work, Santiago Slabodsky, the Florence and Robert Kaufman Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies at Hofstra University, often talks about the historical co-Orientalization of Jews and Muslims.

Yet imperial and capitalist interests continue to position our communities as if locked in an eternal zero-sum game. We see this with heads of state Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu conflating Judaism with Israeli state policies of aggression and expansion in Palestine, and using Islamophobic tropes depicting Muslims as violent and inherently opposed to Western civilization in order to justify a war with Iran.

Trump has made numerous anti-Semitic statements that play into anti-Semitic tropes of dual loyalty, including referring to Netanyahu as “your prime minister” when speaking to U.S. Jewish audiences and accusing U.S. Jewish Democrats of being disloyal to the state of Israel. The president’s deliberate conflation of domestic and Middle East politics and the ongoing bipartisan support for the War on Terror have made U.S. Jews and Muslims embodied sites of political contestation: hate crimes, travel bans, and discrimination continue to draw their bodies into the political battlefield.

In the wake of the December 2019 Hanukkah attack in New York City, Gov. Cuomo announced an increase in security including a $45 million grant administered by the Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services for communications equipment upgrades. This is meant to assuage Jewish communities and make them feel safer.

But actual safety comes from solidarity, not greater state scrutiny and criminalization, which disproportionately impact people of color and vulnerable communities. Employing state forces as barriers between our fractured communities only furthers our fragmentation and contributes to future distrust and misunderstandings.

We, Muslim and Jewish activists based in Rochester, understand this and are committed to a decolonial understanding of our histories and struggles. We aim to stay invested in and show up for one another, and we urge all our diverse communities to do the same. Let’s band together against the rising tides of violence, in our country and across the globe. Solidarity is safety.

Signed,

Mara Ahmed

Fatimah Arshad

Halima Aweis

Nate Baldo

Mawia Elawad

Durdane Hatun Guler

Arseniy Gutnik

Ian Layton

Tori Madway

Lessons of the Hour: A Review [Rochester Beacon, Apr 23, 2019]

Two years ago, Amanda Chestnut, Rachel DeGuzman and I organized a celebration of Frederick Douglass’ 199thbirthday at his gravesite in Mount Hope Cemetery.

The following year, in 2018, the city of Rochester was energized to mark Douglass’s 200thbirthday with multiple community events. Part of this process of excavation included a work of art by Isaac Julien, commissioned by the Memorial Art Gallery.

Recently I went to see Lessons of the Hour—on view at the gallery through May 12—with two activist friends. According to Julien’s own website: “Lessons of the Hour is a poetic meditation on the life and times of Frederick Douglass, the ten-screen film installation proposes a contemplative journey into Douglass’ zeitgeist and its relationship to contemporaneity. The film includes excerpts of Douglass’ most arresting speeches and allusions to his private and public milieus.”

Isaac Julien’s tableaux vivants are gorgeous—that much is unequivocal. Together the 10 screens form a lengthened semicircle. Sitting on a comfortable bench against the back wall, one feels completely surrounded by and submerged in the piece.