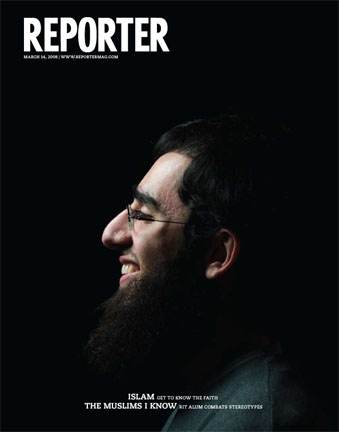

RIT reporter talks about “the muslims i know”

snorkeling at laughing bird caye

belize is located in the southeastern part of the yucatan peninsula. it is home to the 200 mile long belize barrier reef, the longest in the western hemisphere and the second longest in the world.

the beautiful laughing bird caye is only 11 miles off the coast of placencia. the abundance and variety of coral habitats and marine life make this isle truly unique. in 1996 the belize barrier reef reserve system was inscribed on the world heritage list with laughing bird caye national park designated as one of its most closely protected areas. the isle is long and narrow and truly breathtaking.

on our way to the islet, after hitching a boat ride in front of our house right off of the beach, we saw some dolphins. we changed into our gear and went snorkeling in the warm salty water. it felt like being in an aquarium. the coral comes in indescribably vivid colors, the sea fans quivered delicately underwater, and the schools of fish we encountered felt so close it was magical. unfortunately my daughter’s equipment was too big for her so she kept getting salty water in her eyes and mouth. she was a good sport about it but we decided to cut short our exploring to get her to shore. my son scraped his foot on some coral reef and bled quite a bit. thank god the park ranger had some antiseptic ointment and band aids. we had a delicious picnic cooked on the beach (grilled chicken – jamaican style, potatoes roasted in a cheese sauce, sweet coleslaw and fresh pineapple. what a treat! although we could not take any conchs or shells with us i took plenty of photos. we also took some footage of brown pelicans diving for fish. the water was a myriad different shades of blue, each more delightful than the other. it is one of the most beautiful places on earth.

mayan ruins and swimming in caves

our next trip was to toledo, the southern most district in belize. this is mayan country and we were first headed to the mayan ruins of nim li punit. discovered in 1976, this site is situated along the top of a ridge in the foothills of the maya mountains and has a stunning view of the coastal plains below. 25 stelae, 8 of which are carved, were discovered here. stelae are stone slabs, sometimes 50 feet long, with hieroglyphic inscriptions and carvings depicting the lives of mayan rulers. placed within the ceremonial centers of cities, they now provide us a rare glimpse into mayan life. one of the largest structures is a ball court. the mayans played with a hard and heavy rubber ball and the victor was honored with a beheading. for people who believed strongly in the after-life there could not be a better reward.

after the mayan ruins we went for lunch at our guide juan’s home in the village of punta gorda. the trip had been arranged through robert’s grove and they had packed us an “american” lunch – chicken wings, roast chicken and potatoes, watermelon, brownies and a huge salad. of all the lunches we’d had so far this was the least appetizing. juan’s daughter had made some fresh tortillas and these became instant favorites. the bathroom was surprising – let’s just leave it at that.

after lunch we began our rigorous trek through the jungle to the blue creek cave. the trek could have been a little easier if we had not been carrying backbacks, towels, cameras and life jackets. you definitely need both hands to make it without getting hurt. it was hot, the trek was arduous and we were sweating profusely (i had forgotten what it was like to sweat – the suncreen makes it worse by melting on your face). after all this effort it was a shock to suddenly come upon the glistening waterfall and gushing waters of blue creek. this is where the río blanco emerges from the side of a mountain, becoming blue creek – home to an extensive cave system.

we changed into our swimsuits, put on our life jackets and water shoes, adjusted our headlamps and leapt into the freezing waters of blue creek cave. what an experience. the ground under your feet is treacherous to start with (you might be heading for a huge rock or be in rather deep water) but it all becomes easier as you swim farther along into the cave. once we were quite a ways inside we orchestrated a complete blackout by turning off our headlamps in unison – it was pitch black! the cave is quite deep. juan told us it takes three days to swim across all the way to the other side. we didn’t want to find out. after a fun swim and explore we headed back. it had started to drizzle outside and the rocks were getting slipperier by the minute. i tried to jump from one rock to another but my shoes lost their grip and i landed against a rock on my leg. thank god there was no bleeding, just a nasty bruise. my husband was not so lucky. he was carrying 3 life jackets and when he slipped he got pretty badly scraped. but we all made it in one piece. the 2 hour drive back to placencia and the boat ride to seine bight were tiring but it felt good to have had this great adventure!

at the beginning of it all we had met this tourist family who’d been to blue creek. they had recommended the trek but the guy had added ominously “mind you, there will be blood” – i guess he knew what he was talking about!

peace in belize

there is a popular t-shirt you can find in just about every souvenir shop in belize – it says: “where the hell is belize?” and is followed by a map of central america. formerly called the british honduras, belize gained independence in 1981 after a century of british rule. it is bordered by guatemala and mexico. with heavy forestation in the north, the maya mountains in the south, some 450 islets or cayes along its carribean coast and a tropical climate, belize is rife with biodiversity (marine, terrestrial, flora and fauna). human diversity is not bad either. check out this population mix: 50% mestizos (spanish+indigenous american), 25% kriols (african slaves from jamaica), 11% mayan, 6% garifuna (african+indigenous american), and a small percentage of german mennonites (amish), east indians, chinese, other central americans, and whites from the u.s. not bad for a country of 300,000!

our destination was placencia, south of the country in the stann creek district. we stayed at the bahia laguna in seine bight, a small garifuna town. the bahia laguna is a large bungalow and we had use of the spacious apartment on the ground floor. it had everything we could have asked for: kitchen with large refrigerator, dishwasher, even a washer and dryer. there was a swimming pool in the back with a cool slide and the sea was just footsteps away.

after our last vacation i had appreciated for the first time the joy of cooking with local produce and ingredients. we did just that and apart from a lunch at the coloful “purple space monkey” we ate at home everyday. we’d use our complimentary bikes to go to the tiny chinese grocery store in seine bight and buy everything we needed for the next couple of days. we made easy food like hamburgers and mac & cheese but also spicy chicken karahi and okra with lots of fresh tomatoes.

madalon, the owner of the bahia laguna, has a mayan couple living in the other apartment on the ground floor. delmacio works around the house and he and his wife conceptiona are a great addition to the household. conceptiona made some fresh tortillas for us. they were absolutely fabulous and very close to what we in the sub-continent would call tandoori roti. they went beautifully with the curries we cooked.

you would think that there isn’t much to do in belize (and that’s a perfectly good way to spend a vacation) but in fact there’s lots of adventure just waiting to happen. first we embarked on a water safari to explore the environs of the monkey river. our guide terry showed us a lot of exotic plants and birds whilst we sped along in a motorboat. our main stop was the jungle so we could track down some howler monkeys. man, those monkeys are fierce – their howling sounds a lot like screams in a horror movie. we spotted them perched in tall trees, hanging from their prehensile tails. we were lucky to find an entire family of monkeys and i got some terrific footage on my video camera. for lunch we headed to monkey river village and had some fresh fried fish with a sweet potato salad and rice and beans – a staple in belize. it hit the spot.

on our way back home our guide showed us some manatees. these seal-like creatures are herbivores and can weigh up to a ton. they create such a big commotion that they can be easily spotted by the mud they dislodge from the bottom of the sea as they partake of water plants.

elections in pakistan

it’s heartening that the 2008 parliamentary elections were relatively clean, based both on reports by local and foreign observers. no massive rigging and a turnout of 45% – which is impressive considering recent bombings and political assassinations.

what this proves is that the people of pakistan are smart and secular. 61% of the seats were won by secular parties (bhutto’s pakistan people’s party, nawaz sharif’s pakistan muslim league and the northern frontier’s awami national party), only 3% of the vote went to religious parties.

in pakistan’s civil society, there is a real desire for democracy and for negotiated political settlement to end terrorism and militancy. people know that military force is not the answer. political parties want to engage militants and bring them into a participatory democratic process. The question is, will the u.s. government allow this democratic process to flourish or will it continue to work with the pakistan army behind the public’s back and sabotage any long term solutions to the crisis it helped create.

clip from “the muslims i know”

check out a clip from the 60-minute documentary “the muslims i know”:

for those of you who don’t know about the film, here’s a little write up:

If you yahoo the words “moderate Muslim” today you will get more than 8 million hits on the internet. This interest is the result of a post-9/11 Western world trying to make sense of Islam and its followers. The need to identify militant jihadists by distinguishing them from moderate Muslims has cast suspicion on all Muslims in America. Stereotypes are becoming well-entrenched. The purpose of this 60-minute documentary is to deconstruct those stereotypes by showcasing Pakistani American immigrants and asking them questions many non-Muslim Americans have framed through vox pop interviews. The aim is to start a dialogue.

A secondary goal is to educate people about the basic tenets of Islam and celebrate the cultural richness and diversity brought into the American mix by Muslim communities. Footage shot in Lahore, Pakistan, is used to bring this cultural exuberance to life.

Finally, the film answers the question: where are the moderate Muslims? This question is asked to ridiculous excess by the media. The silence (and therefore culpability) of the moderates is still a hot button issue today, seven years after September 11, 2001. By simultaneously asking, “Where are the moderate Muslims” ad nauseum and then excluding them from public discourse, we are slowly coming to the conclusion that there are no moderates. All Muslims are radicals. This is a dangerous conclusion to impose on the American public.

“The Muslims I Know” attempts to redress this imbalance by giving mainstream Muslims a voice and a face – something not often seen in American media.

evie’s waltz

went to see “evie’s waltz” by carter w. lewis at geva theatre. the reading was part of geva’s american voices series.

what an explosive play – full of conflict and contradictions, bitterness, delusions, verbal violence and physical aggression. danny’s bizarre behavior results in his parents’ emotional detachment, especially on the part of his mother. it also invites persistent abuse at school. his friend and neighbor evie has her own problems. her mother has survived her father’s departure and the forced lowering of her expectations by turning to booze. evie is dangerously reckless with a long list of exploits to prove it, such as using a nail gun to pierce her tongue. she and danny have known and loved each other since they were children. together they seem to attain some sense of calm sanity, like partners in a perfect waltz. yet here they are – caught trying to buy a gun on the internet. there are detailed maps of their school stashed inside danny’s locker and a disturbing blood stain on evie’s neck as she shows up for a family barbecue at danny’s house. the play is a fusillade of words that summarizes every strained relationship in the play. danny’s parents argue the bejesus out of anything that comes their way. they have reached a place in their marriage where a spouse is just an irritant in a series of disappointments and verbal jousting is the only means of communication left. evie lashes out at them for all these reasons. she is smart but has her own distorted sense of reality. danny, whom we never see and who is perched in the woods behind his house looking at evie and his parents through the scope of a rifle, participates in the conversation through text messaging and well-timed rifle shots.

the play is well-written with a litany of intense, forceful, actionable language that brings home the clash between incongruous realities. the verbal savagery is an apt vehicle for exposing the violence inherent in 21st century american culture – whether it’s the story of the well-intentioned parents who have lost touch with their child and their own sense of self, the single mother who feels isolated and hopeless, the little girl who learns to act out to forge a sense of identity and acquire a false sense of control, and the little boy who deals with his oddity by taking revenge on the world. although the play is about more than the genesis of a school shooting it nevertheless touches a nerve, especially in view of the latest northern illinois university shootings.

here i have to say how ridiculous i find efforts to prevent such terrible tragedies by trying to identify possible assailants in their early childhood or through sensitivity training or some kind of social discourse where potential problems like violence in films, video games and rap music are happily pointed out. we can analyze our socio-cultural identity and the age we live in until we’re blue in the face. the answers need not be so broad, complex and ultimately impossible to redress. anger is natural and so is social alienation, teenage angst and mental disease. these are things we will never be able to fully understand or regulate unless we start replacing human beings with impeccably-wired robots. humans will be humans. the only thing that makes america different from other countries where school shootings are not commonplace is the easy availability of guns. anger is natural but the snappy and efficacious use of a gun to act out that anger is not!

in pakistan, islam needs democracy

my friend pacho lane sent me this excellent article by waleed ziad. he reiterates many of the facts my husband and i tried to explain in our “open letter to our senators and congress people about the crisis in pakistan” (post filed under “activism” dated 11/21/07). here is the article:

in pakistan, islam needs democracy

WHILE it’s good news that secular moderates are expected to dominate Pakistan’s parliamentary elections on Monday, nobody here thinks the voting will spell the end of militant extremism. Democratic leaders have a poor track record in battling militants and offer no convincing remedies. Pakistan’s military will continue to manage the war against the Taliban and its Qaeda allies, while President Pervez Musharraf will remain America’s primary partner. The only long-term solution may lie in the hands of an overlooked natural ally in the war on terrorism: the Pakistani people.

This may come as a surprise to Americans, but the Wahhabist religion professed by the militants is more foreign to most Pakistanis than Karachi’s 21 KFCs. This is true even of the tribal North-West Frontier Province — after all, a 23-foot-tall Buddha that was severely damaged last fall by the Taliban there had stood serenely for a thousand years amid an orthodox Muslim population.

Last month I was in the village of Pakpattan observing the commemoration of the death of a Muslim Sufi saint from the Punjab — a feast of dance, poetry, music and prayer attended by more than a million people. Religious life in Pakistan has traditionally been synonymous with the gentle spirituality of Sufi mysticism, the traditional pluralistic core of Islam. Even in remote rural areas, spiritual life centers not on doctrinaire seminaries but Sufi shrines; recreation revolves around ostentatious wedding parties and Hollywood, Bollywood and the latter’s Urdu counterpart, Lollywood.

So when the Taliban bomb shrines and hair salons, or ban videos and music, it doesn’t go down well. A resident of the Swat region, the site of many recent Taliban incursions, proudly told me last month that scores of citizens in his village had banded together to drive out encroaching militants. Similarly, in the tribal areas, many local village councils, called jirgas, have summoned the Pakistani Army or conducted independent operations against extremists. Virtually all effective negotiations between the army and militants have involved local councils; in 2006, a jirga in the town of Bara expelled two rival clerics who used their town as a battleground.

The many militant outfits in the frontier regions are far from a unified popular movement. Rather, they are best characterized as ethnic or sectarian gangs, regularly changing names and loyalties. More often than battling the army, they engage each other in violent turf wars. For many of them — some with only a handful of members — “Taliban” is a convenient brand name that awards them the status of international resistance fighters. It is not uncommon for highway bandits to declare themselves Taliban when stealing tape decks from vehicles.

The Taliban franchise that has battled the army for months in the Swat Valley is held by an outfit whose founder marched thousands of local youths to their death in a campaign in Afghanistan in 2002. Upon returning, he virtually solicited his own arrest by Pakistani authorities to escape the vengeance of the victims’ families. The group is now led by one “Mullah Radio” who, armed with an FM station, preaches that polio vaccinations are a Zionist plot and that the 2005 earthquake was retribution for a sinful existence. A worrisome crank, yes, but hardly Osama bin Laden.

The big problem — as verified by a poll released last month by the United States Institute of Peace — is that while the Pakistani public condemns Talibanism, it is also opposed to the way the war on terrorism has been waged in Pakistan. People are horrified by the thousands of civilian and military casualties and the militants’ retaliatory attacks in major cities. Despite promises, very little money is going toward development, education and other public services in the frontier region’s hot zones. This has led to the belief that this war is for “Busharraf” rather than the Pakistani people.

Naturally, Washington must continue working with Mr. Musharraf’s government against extremism. But we also need a new long-term policy like the one outlined by Senator Joe Biden last fall that would strengthen our natural allies and rebuild faith in the United States at the public level.

This isn’t just wishful thinking. Interestingly, the Musharraf era has heralded a freer press in Pakistan than ever before. Dozens of independent TV channels invariably denounce the Taliban, while educational institutions are challenging the Wahhabist ethos. My conversations with Pakistanis, from people on the street to intellectuals, artists and religious leaders, only confirmed that after the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, anti-militant sentiments are at a peak.

This is where the lasting solution lies. As Donya Aziz, a doctor, former member of Parliament and prominent voice in the new generation of female leaders, told me: “Even now, as the public begins to voice its anti-militancy concerns, politicians across the board are seizing the opportunity to incorporate these stands into their political platforms.”

What can America do? Beyond using our influence to push the government to expand democracy and civil society, we need to develop close ties with the jirgas in the violent areas. The locals can inform us of the best ways to infuse civilian aid. (According to Ms. Aziz, “the foremost demand of the tribal representatives had been girls’ schools.”) We should also expand the United States Agency for International Development’s $750 million aid and development package for the federally administered tribal areas.

If next week’s elections are free and fair, it will be an encouraging sign for Pakistan. But as far as Washington is concerned, this should constitute only the first stage of a broader policy intended to make average Pakistanis see the United States as a long-term partner. In the aftermath of the 2005 earthquake, American popularity soared as American aid helicopters — widely called “Angels of Mercy” — soared to the rescue. If we can bear in mind that our long-term interests are the same as those of average Pakistanis, the challenges of fighting the militants and rebuilding credibility may not be as daunting as they seem.

Waleed Ziad, an economic consultant, is an associate at the Truman National Security Project.

are there any pakistani leaders after benazir?

many of my american friends have listened patiently to my views on benazir’s dubious political legacy and lamented the absence of any other viable political leaders in pakistan. that’s a staggering statement. in a country of close to a 166 million people you would think that there would be more than just a couple of political figures. and there are. but it sure doesn’t look that way in the dali-esque world of american media conglomerates and their perfectly buffed and sadly vacuous news coverage. it makes for a thrilling media blitz to glorify benazir as the heroine of pakistani democracy and the only chance pakistan’s ever had to get out of its existential doldrums, but is that an accurate assessment? yes, benazir was from harvard and generally more palatable to an american audience and its elected government but even inside her pakistan people’s party (ppp) she was anything but democratic. having enjoyed the less than kosher title of “chairperson for life”, she made sure that after her death, the mantle would be conveniently passed on to her son.

but coming back to alternative leaders in pakistan.

of course there is nawaz sharif of the pakistan muslim league. he has been the democratically elected prime minister of pakistan twice, from 1990-93 and again from 1997-99. his second term ended rather brusquely when he was deposed by general musharraf in a military coup. he was thereafter exiled to saudi arabia and has now resurfaced to contest the upcoming elections in pakistan. the lowdown on nawaz is this: he is a punjabi industrialist and his group of companies, ittefaq industries, did not do too shabbily during his two terms. like benazir’s government there was blatant corruption, but there was also some flirting with islamic law. he tried to make the quran and sunnah the supreme law of the land. although the amendment was passed by the national assemply, it failed in the senate. nawaz was corrupt and given to self-serving talk of islam, but he was a businessman and many will say especially in lahore, that at least he left a tangible legacy. he made lahore beautiful, overhauled the lahore international airport and oversaw the construction of south asia’s longest highway, extending from lahore to islamabad.

then there is imran khan – cricket star, international playboy, oxford university graduate. from marrying jemima goldsmith to successfully establishing a state of the art cancer hospital and research center in pakistan, imran has done it all. in 1996, he founded a political party, pakistan tehreek-e-insaf or movement for justice. although imran is a celebrity and has had his own personal brush with islamic conservatism, the middle class can relate to him. he says it like it is. he talks sense. he supported the legal community’s fight for the return of the rule of law after musharraf declared a state of emergency and has refused to participate in the february 2008 elections due to the continued dismissal of the judiciary. but due to the fact that he is not a major landowner, industrialist, or military man, his political base is nominal. here is an interview with democracy now!’s amy goodman.

there are many seasoned politicians within the ranks of the ppp, for example makhdoom amin fahim, the party’s vice-chairman. a sindhi landlord with a bent for sufism and poetry, his father was one of the founders of the ppp, along with benazir’s father zulfiqar ali bhutto.

aitzaz ahsan also hails from the ppp. barrister-at-law, human rights activist and co-founder of the human rights commission of pakistan, former federal minister and senator, he is currently president of the pakistani supreme court bar association. aitzaz ahsan became a hero in the people’s movement for democracy and freedom which resisted musharraf’s state of emergency. he has been mostly under house arrest since 2007 for acting as deposed supreme court justice iftikhar chaudhry’s defence lawyer and demanding the restoration of the judiciary, after musharraf sacked 60 of the country’s senior most judges. interestingly enough after benazir returned to pakistan and took stock of this grassroots movement for democracy, she dealt with aitzaz ahsan’s popularity by sidelining him rather than truly joining in the fight.

and of course there is the jamaat-e-islami. although most pakistanis vote for centrist parties rather than those on the religious extreme, it has to be pointed out that jamaat-e-islami is one of the few political parties in pakistan which are truly democratically functional. at this time qazi hussain ahmad is the elected president. there is no chairman for life.

away from her

at a time when big budget films like “atonement” (dizzyingly beautiful cinematography but story-wise much ado about nothing) and “3.10 to yuma” (beautiful wide-lens cinematography but flimsy storyline steadily crumbling into a sad pile of film debris) are making the oscar rounds, it’s good to partake of a film like “away from her”. there is a quiet elegance to this film, a spareness which is not thrust upon you like so many musical scores with too many notes, or a series of impeccably-constructed sets that demand your attention, or clever camera angles that take themselves too seriously. julie christie’s performance is radiant. the dialogue is economical, intelligent. the film’s structure is both skillful and assured. this is the kind of filmmaking i like – terse, nuanced, quiet, poetic, perfect.

consumption – the path to happiness?

the mean bus driver, cioppino and chicken mole

we had dinner at a nice restaurant that offered a fusion of french-southeast asian cuisine. it could have been any nice restaurant in nyc (no mexican angle) but the food was good especially the sate and the delicately flavored shots of creme brulee that came in a friendly trio. after some down-time at our cousin’s apartment we were off to the hotel. the next day the kids registered for the sheratoons (the local kids club) and made some awful smelling cookies. they also swam and took it easy.

we decided to go to the city for lunch and thought the local bus would be an adventure for the kids. we got tickets and even though kids tickets were half the price, the driver charged us full price. i didn’t care much. we told the driver we wanted to get off in the center of town – centro – that was one of the bus’s regular stops. when we got to the city and tried to get off, the driver wouldn’t let us leave. thrice we tried to disembark but he told us to stay put – he knew where we had to get off. my husband trusted him. i was more suspicious. the city of puerto vallarta is tiny (just a couple of main streets) and it was obvious that we were out of the city now. the bus began to climb a hill. it turned a corner and there we were, bang in the middle of pv’s slums. there were no cabs here, no tall american tourists with flashy sunglasses, no shops crammed with talavera pottery or huichol art. this was the ghetto outside of puerto vallarta and well-meaning tourists are not supposed to see it. there were fewer and fewer people in the bus and i began to panic. i didn’t want to go wherever this guy was taking us. maybe we should just get off anywhere. but how would we get back? finally, after an hour of chugging along, we reached the end of the bus route. the bus driver asked my husband to pay for tickets if we wanted to get back to the city. so that’s what it was all about! i was furious. i refused to pay. my husband tried to explain in spanish but the driver insisted. “non comprende” was the way to end the argument and so it was that we were finally dropped off in downtown pv.

one night, after a day of shopping for pottery and rugs, we had dinner at our cousin’s apartment. her friends, pierre and hillary, were excellent company. pierre made some delicious cioppino with fresh fish and shrimp. cioppino is supposed to be san francisco’s answer to bouillabaisse and since our cousin and her friends are all from the west coast, it figured. the kids had a relaxed evening – lazing around, watching tv, and eating fire-roasted chicken, avocados, and french bread dipped in cioppino, with mango ice cream and guavas for dessert. it was a lovely evening.

we ate out on our last day at a mexican (mariachi and all) restaurant. i had some chicken mole. although the mole sauce was dark and rich and delicious the chicken was hard to tackle. it looked like pv was gearing up for new year’s eve but we were off early next morning, back to rochester and some mind-numbing below zero weather. mexico had been one helluva holiday!

andee’s blog: mylifeinchacala

our stay in chacala was fabulous – it was the real thing. fewer tourists, more interaction with local people, excellent food. there was a certain simplicity and charm to it. initially we had planned on staying at mare de jade, a beautiful retreat that offers both accomodation and meals. when that didn’t work out i began to look on the web. i found a blog called “mylifeinchacala“, a treasure trove of facts and information, with colorful pictures and personal recommendations. it was written by an american woman called andee carlsson. i emailed andee a couple of times and finally decided on casa monarca – i had read about it and seen the pictures on her blog.

while writing my posts about mexico, i went back to andee’s blog. the first thing i saw was a picture of her. i scrolled down, more pictures. i was surprised. having navigated andee’s blog in quite some detail while deciding on a place to stay, i had noticed how there were no pictures of her anywhere. i even tried to imagine what she looked like.

as i read on, i was shocked to find a post by her son, saying that andee had passed away on jan 16. we were in chacala last december and i had regretted not having had time to seek andee out and say hello. i guess that was not to be. even though i never met her, i was touched by andee’s sweetness and i just wanted to acknowledge that.

rest in peace andee, under chacala’s beautiful blue sky.

chacala and puerto vallarta

our first morning in chacala we went to the beach for breakfast and then on to the local market, video camera in hand. my son was my guide throughout this trip and did a wonderful job of navigating mexico complete with fun-facts and witty commentary. our first stop was a small souvenir shop where the guide in question purchased some flip flops. i had suggested as much while packing for the trip back in rochester, but mr middle school didn’t want to wear flip flops. we had settled on water shoes, luckily at hand from our lake house. however, in his haste to return to his psp, mr middle school had picked out 2 left shoes from the bunch – one was his own and one was his dad’s. since it is never advisable to have a guide with 2 left feet we decided to take care of that first.

we just strolled down the tiny bazaar. i bought some pottery. we tried authentic burritos, made on a stainless steel surface. they were good but would have been better if we had been allowed to try the sauces – my husband was at it again, making sure we only ate things that were steaming hot. after lunch we took it easy at casa monarca. my daughter spent several hours intermittently swimming in the pool and swinging in a hammock.

i had read on the web that chacala is always in need of school supplies, so i brought a bagful of school supplies and toys with me. kate told me to take them to mary ann day, co-founder of cambiando vidas (“changing lives”), a non-profit that provides academic support and social enrichment to the chacala community through a learning center, scholarships, computers and internet access, etc. mary ann lives on the top floor of casa aurora. my husband and i decided to walk there. we chatted with mary ann for quite a bit. she told us about the building boom beginning to take root in chacala, thanks to american developers looking to capitalize on chacala’s beach front potential. many of the bigger houses she told us belonged to americans. “i told the local people not to sell their land. i told them the gringos were coming – i ought to know, i’m a gringa!”. it will be a shame if chacala’s present way of life gets lost in the gated, shiny and greedy commerciality of big-ass hotel chains and resorts. mary ann believes it’s only a matter of time.

after some savory dinner (shrimp cooked with chunks of garlic – it had a definite kick) we got back home and began to pack up for our trip back to puerto vallarta the following day. i made the unpleasant acquaintance of a tiny gecko inside our house. it reminded me of pakistani lizards and i wasn’t too happy. thank god my husband is not afraid of anything and he took it out for me. the kids were very concerned for the gecko’s safety so the extradition process was a delicate affair.

we left for pv on thursday, which was perfect. thursday is farmers market day. en route we stopped at la penita mercado. what fun! the market was swarming with sellers. there were rugs, jewelry, pottery, wall hangings, paintings, and lots of fresh produce. i shopped to my heart’s content, trying to keep track of how much i would be able to squeeze into our suitcases. after the mercado we drove to pv, returned the car and took a cab to our hotel – the sheraton. my kids were visibly relieved by the sheer size and shininess of our new abode. the view from our room was stunning. the hotel was literally on the beach, just footsteps away from the sea. after escaping the hotel personnel (they were bent on making us all kinds of rich offers if we agreed to give them 1 1/2 hour of our vacation time to check out the hotel’s rental property) we had an excellent lunch at one of the many restaurants located within the resort. the kids were off on an explore. my son was soon remarkably well-versed in everything that had to do with the hotel – he had the lowdown on the sheraton.

later that evening, my husband’s cousin arrived. she was the reason we had made this trip. a frequent traveler to mexico and especially to pv, she was going to take us to town. we got into a cab and went to the apartment she had rented along with some friends. the apartment was built on top of a hill and looked deceptively like a big villa. it was in fact an entire building full of apartments that sprawled vertically along the slope of the hill and provided amazing views of the city at many different levels. the interior was beautifully decorated and replete with mexican craftwork. we were now ready to walk down the steps from the apartment, to the city of puerto vallarta!