watched the first 4 episodes of ‘we are lady parts.’ wow. it’s one of the best shows i’ve seen. ever. nida manzoor (the writer, creator, director) is an absolute genius. how long have we (muslim/brown) women waited for something like this. can a show this creative and trope-free even be produced in america? i hope so. we need more.

Category: reviews

immersive van gogh in nyc

immersive van gogh at pier 36 felt like a touristy thing to do, but i got to see my lovely kids and have brunch with them, so what could be better? my deep connection to van gogh: i read “lust for life,” irving stone’s biography (a comprehensive tome on van gogh’s life and work but also on impressionism broadly) when i was in high school. his tragic story and gorgeous art (it pulsates with color and intensity) have been with me all my life and perhaps became a lens through which i learned to appreciate all art.

at the end of the show, we finally come face to face with van gogh’s self portraits, to the sound of handel’s saraband, and it strikes one what a hard, sometimes brutal, life he lived and how commercially profitable his art has become now. i hope that his brother’s family is getting a piece of it still, his brother theo who supported him through all the illnesses and crises.

pier 36’s “75,000 square foot waterfront space located in manhattan’s lower east side” didn’t really work for me. i prefer the intimacy of arttechouse for a truly immersive experience, but this is a great instagram opportunity.

more shahzia sikander

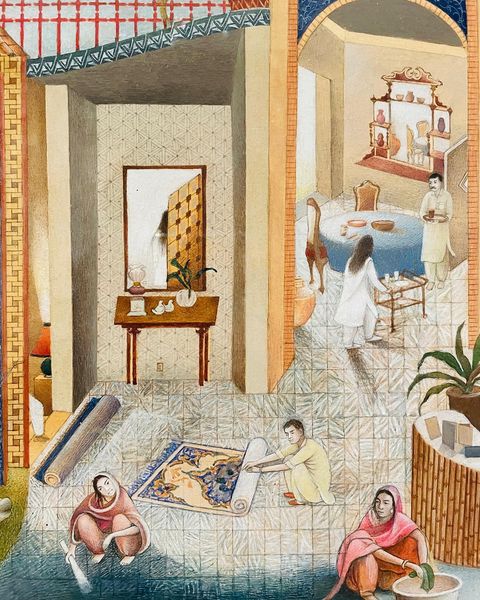

imaginary man

shahzia sikander. miniature in mughal style: imaginary man, 1991 (vegetable color, watercolor, tea, and gold leaf on wasli paper, 11 x 8 inches). this piece made me tear up. its exquisite detail, the subdued color palette, the delicate hands and fingers, the otherworldly beauty of this serene male figure — a bearded, muslim figure and all that it has come to mean in the western imaginary, yet here it is, portrayed as something distinguished and light, frail rather than threatening, gossamer rather than immovable. i stood there for a long time, coming close to the piece and connecting with the arduous, detail-oriented work that went into creating this dazzling art. it took sikander years to complete it.

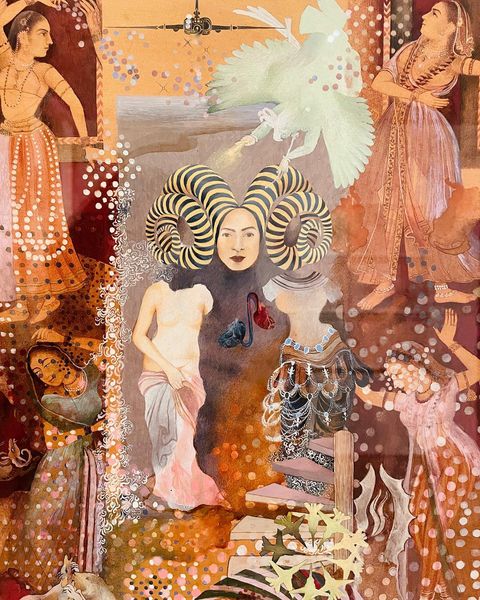

shahzia sikander: extraordinary realities

this past weekend, my sister, daughter and i went to see ‘shahzia sikander: extraordinary realities’ at the morgan library and museum in nyc. a tremendous exhibition even though it spans the first 15 years of her work only. she moved to the US the same year i did, in 1993, and i’ve been following her work since the 90s. rooted in rigorous research, filled with symbolism and iconography, unafraid to engage with the politics of empire, race and patriarchy, bent on creating a unique and personal vocabulary, sikander’s work is bold, original, and always ahead of its time. it is also beautiful – many pieces painted painstakingly over years. the details are astonishing, the overall impact of her images almost mystical (in how they simultaneously activate the mind and enchant the eyes), and the narrative intricacies of her work (with its rich subtext and references) demand attention. that she is an artist from lahore, educated at the national college of arts (NCA), who studied miniature painting under the tutelage of professor bashir ahmad, makes her all the more special to pakistanis. my daughter read every art label and took pictures of every artwork. she told me it was the best exhibition she’d ever been to. it’s moving to encounter extraordinary art. it’s sublime to recognize bits and pieces of oneself in it. i will be sharing images in several posts. as molly crabapple has said: if u are in ny, u owe it to yourself to see this exhibition.

‘Blindness’ at the Daryl Roth Theatre

In early May, we went to see ‘Blindness’ at the Daryl Roth Theatre in NYC. It’s ‘José Saramago’s timely, sinister story of a world in chaos… narrated with savage rage by Juliet Stevenson.’

Blindness is no ordinary play. Its setup is designed specifically for Covid-appropriate social distancing. This is how it works: People are ‘grouped in pairs who have come together… distanced from other pairs, and, at first, each pair sits under its own spotlight. There is no stage; the show occurs only in light and sound. Above audience members’ heads are a series of glowing neon tubes in primary and secondary colors, perfectly vertical and horizontal and meeting at right angles, reminiscent of the work of the artist Dan Flavin. The story, ably delivered, in a recorded monologue, by Stevenson, comes through headphones sporting “binaural” 3-D technology.’

The neon tubes move up and down, and for vast portions of the play, we are immersed in complete darkness.

As Kate Wyver wrote in the Guardian, ‘the piece is claustrophobic by nature, but when wearing the required mask… breathing suddenly feels much harder. At these points, the lack of sight is disorienting and the binaural sound design properly takes effect as the violence of the piece crawls beneath your skin. It feels as if Stevenson is whispering right into your ear, stroking your arm, holding that dripping knife.’

Light and sound have never been used more effectively to create patterns, moods, textures, and a sense of space and time. I was not surprised to learn that this is a Donmar Warehouse (London) production. I saw ‘Julius Caesar’ set in a women’s prison, brought to pulsating life by an all-female cast in 2012. Never forgot it.

The play’s narrator, or Storyteller, is voiced by the incredible Juliet Stevenson who’s absolutely dazzling here.

One of the strongest moments for me was towards the end, when the exit door opens. At that moment, Stevenson is describing her scarred city, come to a violent halt, littered with corpses, garbage, and dogs tearing apart flesh from the freshly fallen. That hell comes to an end, like a bad dream, when the door opens. We see a swath of beautiful green, welcome respite for deprived eyes. Yellow cabs pass by in the distance, pedestrians much closer to us. We hear the faint hum of a functioning city. Such relief and emotion.

Makes one wonder how a breakdown in food systems and other services would impact New York, how the idea of modern cities in general is ridiculous – rendering people helpless, isolated, vulnerable to shocks, fragile.

I was left with some thoughts about Saramago’s book. How he uses blindness as a metaphor — the stripping away “of the mirrors to the soul,” which ‘loosens the fragility of human and psychic bonds, and divests us of the will and rationale to maintain them.’

‘Near the end of the novel, when the blind people are getting their vision back, he has one of his characters remark:” I don’t think we did go blind, I think we are blind, Blind but seeing, Blind people who can see, but do not see.”’

Although Saramago’s blindness is a ‘white disease,’ a ‘milky sea’ that spreads by visual contact, like the evil eye, an analysis of the text thru the lens of Disability Studies is important. A little surprised that in a city, where a raging, highly infectious white blindness is breaking down existing systems, people who are already blind (and adjusted) don’t play a more powerful, positive, central role. Less comfortable with the fact that Saramago’s Storyteller/protagonist (she is the all seer, leader, organizer, moral compass of the story) is the only person who has sight.

A remarkable experience all in all, and very much in line with my interest in audio storytelling (the Warp & Weft).

there is a ceasefire but what’s next?

there is a ceasefire in place at the moment with a break in the bombing of gaza, thank god, but that does not change the reality of settler colonialism, ongoing ethnic cleansing, apartheid, an illegal blockade, military occupation, the imprisonment of children, checkpoints that negate freedom of movement, and non-stop human rights violations. this has been going on, in various forms, since 1948.

it’s been painful to read posts on social media, by well-meaning people who couch their support in abstract language, never mention israel as the aggressor/colonizer, or engage in bothsidesism (pray for both sides, mourn lives lost on both sides, there are extremists on both sides, etc). essentially, they are affirming the equivalent of ‘all lives matter.’

the majority of people have been silent which is even more unsettling.

consider this:

israel has one of the best equipped militaries in the world (thx to our tax dollars), palestinians do not have an army, air force or navy. they don’t control their borders, with no sovereign title over the west bank or gaza strip. this is why we see the obscene disparity in numbers of people killed and wounded.

another set of numbers might be helpful:

per capita GDP for gaza: $876

per capital GDP for israel: $34,185

gaza is sealed from all sides by israel. every few years they ‘cut the grass’ by bombing one of the most densely populated areas in the world. then they don’t allow concrete in, so palestinians can’t rebuild their homes. materials needed to construct vital water infrastructure are not permitted either so there’s a chronic water crisis in gaza. israel limits the amount of electricity gaza can access per day. they even restrict the amount of calories allowed for its population by blocking food.

another interesting fact:

children constitute about half of gaza’s population. the median age is 17.

there is no reason for not knowing – this information is freely available, a lot of it provided by the UN.

i look at this media/social media landscape and understand why grotesque crimes against humanity have been possible in history. it’s easy to look back and decry slavery and genocide. it’s much harder to recognize it, speak about it, and resist it while it’s happening.

those who have spoken up, written posts, made calls, protested, declared their position and invited wrath from their communities, thank you. we see you and we find hope in ur integrity. “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” inshallah.

A Thin Wall now free on the Bandra Film Festival channel

Dear friends, A Thin Wall is now free to watch on the Bandra Film Festival channel on YouTube. Produced by Surbhi Dewan and myself and shot on both sides of the India-Pakistan border, it is our love letter to all those who were lost and displaced, forced to leave home and cross colonial lines. From the wonderful review by @ind.igenous: “Filmmaker Mara Ahmed’s documentary, ‘A Thin Wall’ is a haunting and thought-provoking account of the partition. Strung together are stories, memories and experiences of those who suffered, leaving behind what they called home, plunging into the unknown. Yet, like wilted flowers inside an old book, love still remains on each side of the border. The documentary reminds one of Zarina Hashmi’s art, of a constant search for home, and the pain of separation.”

tahar rahim in ‘the serpent’

when i first saw tahar rahim in jacques audiard’s ‘a prophet,’ i knew we had struck gold. an actor of immense power and intensity. i thought he would be all over hollywood in no time, but he wasn’t. incomprehensible. glad things are changing. he was in ‘the mauritanian,’ a role for which he’s garnered praise. but he’s even more masterful (and completely in his element) in ‘the serpent’ (netflix). a disturbing character, performed deliciously. rahim is the son of algerian immigrants from oran, who settled in the eastern part of france. with all the islamophobic, racist grotesquerie going on in france, it does the heart good to see him come into his own as one of the most charismatic actors in the world.

the present

‘the present’ is a palestinian short film directed by farah nabulsi and nominated for an oscar. now available on netflix. it opens a small window and gives us a peek into what it’s like to live under occupation. although i know about settler colonialism in palestine, i couldn’t help but feel the horror and humiliation of it in my bones. pls watch.

The Debt We Owe Edward Said

Kaleem Hawa: “Edward Said was our prince,” the Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif recently said in a conversation reflecting on the Palestinian public intellectual’s life and writings. An incomparable thinker, Said is credited with founding postcolonial studies, penning histories of cultural representation and “the Other,” and, in so doing, upending the Anglo-American academy. His Orientalism, published in 1978, is among the most cited books in modern history, by some accounts above Marx’s Capital and Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Throughout decades of essays, books, and reviews, Said showed his care for form and the structures of feeling, seeing in their examination a means of understanding music, literature, the world, and Palestine, his home.

Said was many other things—a critic, a dandy, a narcissist, a mentor, a polemicist, and a singular wit. In 1995’s Peace and Its Discontents—the first of his books intended for an Arab audience—Said describes the Oslo Accords as a “degrading spectacle of Yasser Arafat thanking everyone for what amounted to a suspension of his people’s rights,” shrouded in the “fatuous solemnity of Bill Clinton’s performance, like a twentieth century Roman empire shepherding two vassal knights through rituals of reconciliation and obeisance.” The Palestinian leader for decades, Arafat would come to ban Said’s books in the West Bank and Gaza, a result of Said’s early positions in support of the one-state solution and his criticisms of Oslo.

Said’s commitment to the liberation of the Palestinian people made him enemies closer to home as well. Late in his life, and after 9/11, Said felt isolated by his American friends and colleagues, as if they had “suddenly discovered they were imperialists after all, and had turned themselves into mouthpieces for the status quo,” as he said in one of his final interviews, filmed by English documentarian Mike Dibb in 2003, just a few months before leukemia would take Said’s life. After being faced with the capricious nature of American letters, Said found solace among Arabs.

Many who opposed Said’s political commitments to Palestine spent years attempting to tear him down, and those who owe a debt to him as a person and a scholar have had to rely on private conversations and his own enormous œuvre to contest those depictions. Timothy Brennan, an author and professor who was Said’s former graduate student and a close friend, has attempted to change that with Places of Mind, his biography of Said.

As the reviews of the book have come in, though, it has been dispiriting to see a procession of white writers get Said wrong. Dwight Garner, in his review for The New York Times, “A Study of Edward Said, One of the Most Interesting Men of His Time,” seems to find every possible thing interesting about Said except his identity as a Palestinian, devoting more lines to Said’s sex life than his views on the liberation of his own people. This reflects Garner’s paper’s own treatment of Said when he was alive (The New York Times Book Review published Said 10 times, zero times on Palestine) and echoes its consistent overlooking of Palestinian voices—publishing almost 2,500 op-eds on Palestine since 1970, with only 46 authored by Palestinians. This recent review only furthers something white critics have always misunderstood about Said: In treating his Palestinian identity as a curiosity rather than an animating feature of his life and work, they miss how generative the experiences of the (albeit privileged) colonial subject were to the writing of Orientalism (or Beginnings, Covering Islam, and The Question of Palestine, for that matter). These currents are convincingly traced in Brennan’s intellectual history.

In our conversation, Brennan discusses Said’s literary influences, his relationship to Marxism, his views on the growing movement to boycott Israel, his friendship with anti-war leader Eqbal Ahmed, and his experiences with the New York media. More here.

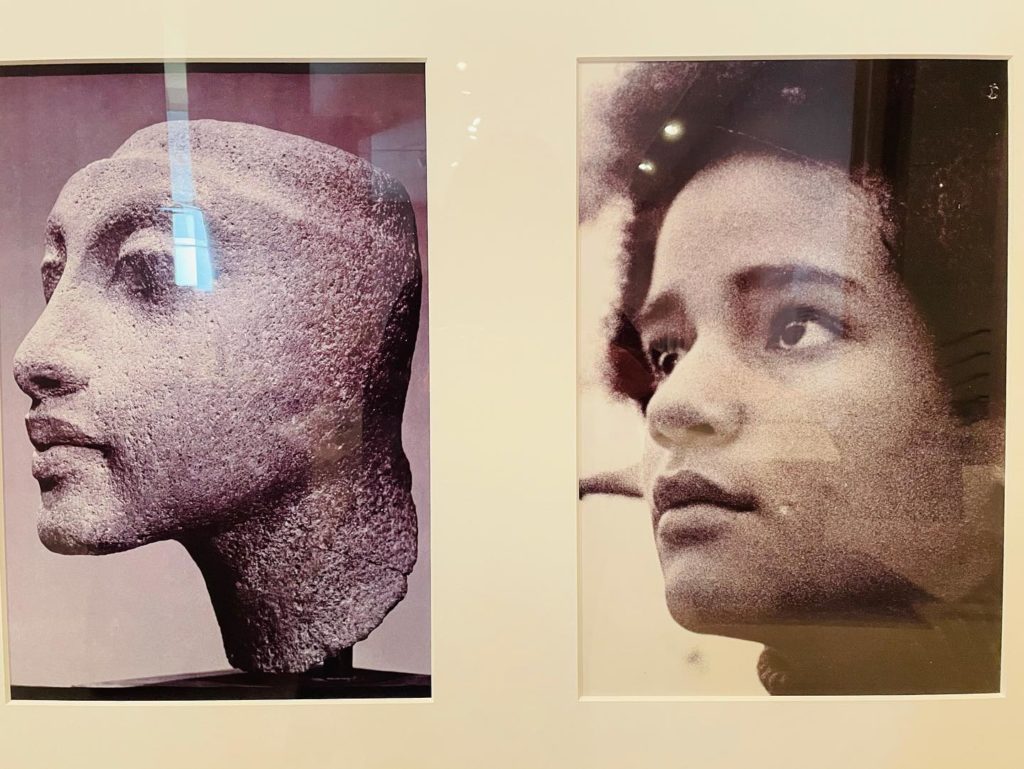

lorraine o’grady’s ‘miscegenated family album’

o’grady’s iconic ‘miscegenated family album’ (1980/1994) consisting of 16 diptychs of photographs that compare her sister devonia’s family to that of nefertiti, is displayed right in the middle of the museums’s egyptian art gallery. the title of this work reclaims the pejorative term “miscegenation.” here’s some background on the series:

‘When the Boston-born, New York–based artist Lorraine O’Grady (born 1934) visited Egypt in her 20s, two years after the unexpected death of her sister, she found herself surrounded for the first time by people who looked like her. While walking the streets of Cairo, the loss of her only sibling, Devonia, became confounded with the image of “a larger family gained.” Upon returning to the US, O’Grady began painstaking research on ancient Egypt, particularly the Amarna period of Nefertiti and Akhenaton, finding narrative and visual resemblances between their family and her own.’

day at the brooklyn museum

spent wednesday at the @brooklynmuseum to see lorraine o’grady’s ‘both/and’ and loved it. both/and represents o’grady’s refusal to kowtow to binaries and western ‘either/or’ thinking. she challenges white-centered art history and how ‘museums enforce both literal and conceptual segregation in the art world.’ in line with this thinking, the brooklyn museum has displayed o’grady’s art throughout their galleries, ‘revealing her critical interventions in these dominant histories.’ so for example, her ‘announcement of a new persona,’ with its lush, large size, staged photographic prints, is mixed together with rodin’s expressive, muscular sculptures. makes complete sense. one work elevates the other, divulging emotions and details one might have missed otherwise.

“The Warp and Weft” Weaves Stories Reflecting on an Unprecedented Year

The wonderful Abi Rose did this excellent story on the Warp & Weft for Reclaiming the Narrative. Pls listen here.

salman toor at the whitney

why i came to nyc: stunning work by salman toor, born in lahore, at the whitney. his first solo exhibition: stories of queer brown men as they negotiate the distance between new york and pakistan. the expressive faces and hands in his paintings are exceptionally rendered. so many things that strike one as immediately recognizable – the turn of a head whilst sitting down for tea, the passive acceptance of extra security checks at customs and immigration, the anxiety of being questioned by pakistani cops when on a date, etc. am still here. still discovering.

.

whitneymuseum #salmantoor #lahore #pakistan #newyork #newyorkcity #art #figurativepainting #oilpainting #queerbrown