Christy Lee Rogers is a self-taught photographer from Kailua, Hawaii. Her obsession with water as a medium for breaking the conventions of contemporary photography has led to her work being compared to Baroque painting masters like Caravaggio. With an eye for the chiaroscuro qualities of light, her subjects bend and distort; bathing in darkness, isolated by light, and are brought to life by ones own imagination. Without the use of post-production manipulation, her works are made in-camera, on the spot, in water and at night.

Category: reviews

The Irresponsibility of ‘What Happened, Miss Simone?’

i don’t agree with everything in this article, but i wasn’t blown away by liz garbus’s film. footage of nina simone was obviously invaluable. how the film was constructed in the absence of nina simone’s own voice, is debatable.

…

Tanya Steele: Is it possible to experience a Black woman as a genius and show her process, highlight what informed that genius, versus shaping a narrative that is weighted toward her “damage”? More here.

wael shawky at moma ps1

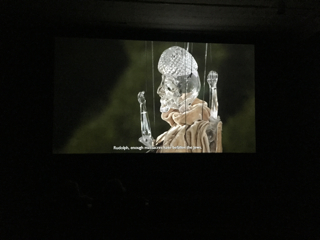

in nyc over the weekend to see wael shawky’s work at moma ps1. shawky is an egyptian artist whose film trilogy “cabaret crusades” is on exhibit for the first time in the US. it’s absolutely mind-blowing. he uses marionettes to retell the complicated history of the crusades (yes, the idea of “manipulation” is not incidental). the narrative at the base of all three films is inspired by “the crusades through arab eyes” by lebanese historian amin maalouf. the first two films employ ceramic marionettes: some are 200 year old puppets preserved in a french museum and others are replicas created by artisans in provence. the last film, “cabaret crusades: the secrets of karbala” uses stunning glass marionettes designed by shawky and rooted in african sculpture. they were fashioned by venetian glassblowers and clothed in period costumes by an italian tailor. each sculpture is unique and bizarre and arresting. their eyes blink with a delicate clink of glass. their movements are elaborate and the tableaux they create are visually beautiful and surreal. all three films are in arabic. it’s interesting to hear the franks and pope urban speak in the same language as salah ud din. they talk of damascus, aleppo, homs, jerusalem, baghdad and constantinople. the horrific violence and political intrigue from those times seems to be tragically apropos today. pls make the time to see this exhibition. wael shawky’s work is dazzling.

Nina Simone: ‘Are you ready to burn buildings?’

cannot wait to see this. on netflix starting june 26.

…

From singing the soundtrack to the civil rights movement to living in self-imposed exile in Liberia, Nina Simone never chose the easy path. As a new documentary is released, Dorian Lynskey looks at the angry, lonely life of a soul legend. More here.

The Lady In Number 6 Music Saved My Life

absolutely love alice.

‘A Thin Wall’ Puts People’s Stories at Forefront of History

Derek Scarlino and Stephanie Inserra both traveled from Utica to Rochester to attend the premiere of A THIN WALL for the Love and Rage Media Collective. Here is their wonderful review!

…

Through its personal stories, artwork and animation, Mara Ahmed’s A Thin Wall is a moving, thoughtful addition to the stories of refugees and immigrant communities throughout the melting pot of the United States. It provides a refreshing, organic look at history how it was lived by its actual witnesses as opposed to being told in a more traditional fashion by third parties focusing exclusively on notable social movements and leaders. More here.

A THIN WALL reviewed in City News

Adam Lubitow of City News reviews “A Thin Wall” in today’s paper:

In her lyrically non-linear documentary “A Thin Wall,” local filmmaker Mara Ahmed focuses on the lingering effects of the partitioning of India in 1947. Filmed on each side of the border — in both India and Pakistan — the deeply personal production allows Ahmed and co-producer Surbhi Dewan to examine their individual histories, assembling the recollections of family members and close friends, along with on-the-street conversations with citizens of both countries. What emerges is a complicated portrait of a people torn apart by arbitrary lines and still feeling the effects of the deaths, displacement, and mass migration that resulted.

We hear from each family as they share stories of their lives before and after the division, explaining the devastating effect it had on their loved ones and the culture at large. By focusing on these personal narratives, Ahmed creates a powerful and intimate account of history. “A Thin Wall” mixes in art, animation, music, and literary writing — including pieces by British poet John Siddique, Pakistani writer Uzma Aslam Khan, and Indian historian Urvashi Butalia — weaving together a rich tapestry of history, memory, and loss, while imploring us to retain the lessons taught to us by the past. More here.

Join us for a one-time screening of the film at the Little Theatre on April 10, 2015 at 7:00 pm. More info here.

greentopia events at urban forest cinema

march 19, 2015: went to the urban forest cinema yesterday along with my friend sarita for a series of greentopia events. the discussion on THE INTERSECTION OF DOCUMENTARY FILM & JOURNALISM (something i know something about) would have been lackluster if it hadn’t been for carvin eisen who challenged mainstream media in the presence of mainstream media (yay chomsky!). “green drinks” was fun and provided an opportunity to connect with people. the MULTI-MEDIA MUSIC AND FILM EVENT “consigned to oblivion” was a great idea (live music accompanied by spoken word and film) but didn’t pan out for me. however, i loved all the locally produced short films which told the stories of wonderful activists and communities doing wonderful things in rochester. these included: Bread For All, The Sweet Bee, and Food For Thought: Seedfolk Stories. and let’s not forget the location – love high falls.

What the Hell is Wrong With This Book: Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission

Jeanne Kay: In Houellebecq’s world, Islam is never interrogated. It is a monolith that appears fully formed and immutable to the reader and french citizens alike, like the perfect embodiment of their prejudices and fears. When Ben Abbes gets in power, women leave the labour force; polygyny becomes commonplace; education becomes privatised and religious; Jews must flee to Israel; wealthy petro-monarchies of the gulf compete to control key French institutions. It’s as if all of the french Islamophobic fantasies are projected onto what Houellebecq merely calls “Islam” without a hint of either imagination or historical veracity. In fact, the whole book is a projection of Houellebecq’s own fantasies. […] Soumission has been hailed as a new 1984, a visionary novel, but it is in fact exactly the opposite: the agonising convulsion of the dying corpse of straight-white western patriarchy, its trembling rage at its gradual loss of absolute domination, its livid horror at seeing its empire escape. In the end it expresses not the truth about French society, not a reality about the supposed tragic decadence of western civilization, but instead its dominating class’s utter lack of imagination, the pitiful narrowness of its spirit, the absolute scantiness of its potential for thinking the world beyond the walls of its miserable, petty little borders. More here.

American Sniper?

Ross Caputi: The most insightful part of this film is what is not in it. However, I believe that these omissions reflect more than just what the director decided to be irrelevant to the plot. These omissions reveal an unconscious psychological process that shields our ideas about who we are as individuals and as a nation. This process, known as “moral disengagement”, is extremely common in militaristic societies. But what is fascinating about American Sniper is how these omissions survive in the face of overwhelming evidence of the crimes that Chris Kyle participated in. The fact that a man who participated in the 2nd siege of Fallujah — an operation that killed between 4,000 to 6,000 civilians, displaced 200,000, and may have created an epidemic of birth defects and cancers — can come home, be embraced as a hero, be celebrated for the number of people he has killed, write a bestselling book based on that experience, and have it made into a Hollywood film is something that we need to reflect on as a society. It is not my intention to accuse Chris Kyle of committing war crimes as an individual, or to attack his character in any way. Some critics have pointed out the many racist and anti-Islamic comments that Chris made in his autobiography (these comments are significantly toned down in the film). Others have noted his jingoistic beliefs. However, I too participated in the 2nd siege of Fallujah as a US Marine. And like Chris, I said some racist and despicable things while I was in Iraq. I am in no position to judge this man, nor do I think it is important to do so. I am far more interested in our reaction as a society to Chris Kyle, than I am in the nuances of his personality.

[…] It was not the actions of individuals that made the 2nd siege of Fallujah the atrocity that was. It was the way the mission was structured and orchestrated. The US did not treat military action as a last resort. The peace negotiations with the leadership in Fallujah were canceled by the US. And almost no effort was taken to make a distinction between civilian men and combatants. In fact, in many instances civilians and combatants were deliberately conflated. All military aged males were forced to stay within the city limits of Fallujah (women and children were warned to flee the city) regardless of whether there was any evidence that they had picked up arms against the Americans. Also, water and electricity was cut to the entire city, and humanitarian aid was turned away. Thus, an estimated 50,000 civilians were trapped in their city during this month long siege without water or electricity and very limited supplies of food. They also had to survive a ground siege that was conducted with indiscriminate tactics and weapons, like the use of reconnaissance-by-fire, white phosphorous, and the bombing of residential neighborhoods. The main hospital was also treated as a military target. The end result was a human tragedy, an event that should be remembered alongside other US atrocities like the massacres at Wounded Knee or My Lai. But none of these documented facts come through in American Sniper. More here.

Ayad Akhtar on “American Dervish: Muslim American Culture and Family Life”

nov 11, 2014: attended an ayad akhtar lecture yesterday at the u of r. he’s won the pulitzer for his play “disgraced” which is on broadway right now. i am happy for his success. i haven’t read his books or seen his plays but here are some thoughts about his lecture and the themes that seem to permeate his work.

i understand that it’s an impossible burden to be the member of a minority and to be expected to represent that entire community accurately, comprehensively, perennially. as the token muslim in most situations, i understand how ridiculous and unjust it is to expect one person to speak for 100s, 1000s, millions or 1.6 billion! it’s impossible to be everything to everyone at all times. as an artist, i understand that it is not the artist’s job to represent anyone but themselves, to have free artistic rein, to be concerned solely with the perfection of their craft. however, if most of an artist’s work is centered on certain aspects of their identity (their muslimness, their pakistaniness or their pakistani-americanness) then they are taking on that burden of representation willingly.

since v few muslims/pakistanis/pakistani-americans are able to attain meteoric mainstream success and the media exposure that comes with it, the content of a successful artist’s craft, deeply rooted within one small exoticized group, becomes more significant. not only will their work be scrutinized by their own community, but they will also participate actively in creating the dominant narrative – the lens thru which this minority is viewed.

here are brief descriptions of akhtar’s work:

[His film] The War Within is the story of Hassan, a Pakistani engineering student in Paris who is apprehended by American intelligence services for suspected terrorist activities. After his interrogation, Hassan undergoes a radical transformation and embarks upon a terrorist mission, surreptitiously entering the United States to join a cell based in New York City.

To appreciate the relevance of playwright Ayad Akhtar’s work, you need look no further than two eerie coincidences that shadowed his debut drama, “Disgraced.” The play, which portrays the downfall of a Muslim American lawyer, won the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 2013. The day the award was announced, two Muslims deposited pressure-cooker bombs near the finish line of the Boston marathon. A second grisly coincidence came a few weeks later. On the day “Disgraced” opened in London two Muslims murdered and tried to behead a British soldier on a busy street in what one said was revenge for the British army’s killing of Muslims in Iraq and Afghanistan. Nobody linked these attacks to Akhtar’s play, but they were nonetheless chilling reminders of the violence that hovers at the edges of the territory he explores. “The work I’m doing is in direct dialogue with what’s happening in the Muslim world,” he said recently over dinner in New York.

[His play] “The Invisible Hand.” It’s the story of Nick, a stock and bond trader based in Pakistan who is kidnapped by Muslim extremists. Although the play examines some of the personal ramifications of the ongoing conflict between the Muslim Middle East and secular Western beliefs, Akhtar sees it as more of a story about global finance.

[His play] The Who and the What: Dark clouds appear early, as Mahwish covertly engages in some Quran-flouting canoodling to keep her fiance on the hook. Meanwhile Zarina — still resenting [her father] Afzal for breaking up her engagement to an Irish Catholic years before — is buried in an incendiary fiction project which will both personalize the Prophet as a flawed, lusting male, and indict the Muslim practice of veiling women as cruelly oppressive and theologically skewed. (Real-life activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali is evoked to point up the provocation.)

Ayad Akhtar is the author of the critically acclaimed, poignant, coming-of-age novel American Dervish. Since its debut,the book has been embraced around the world for the richness of its characters and illuminating the everyday lives of Muslim Americans, earning Akhtar a rightful place alongside today’s most compelling storytellers…The novel centers on one family’s struggle to identify both as Muslim and American, one boy’s devotion to his faith, and the sometimes tragic implications of extremism.

needless to say, akhtar is in constant dialogue with muslim-americanness. but it’s hugely disappointing that this engagement is based, almost exclusively, on stereotypes nurtured by mainstream media.

last night akhtar mentioned how his first book was a complete failure. i was interested in what kind of book that might have been and i found this information particularly enlightening. “At this time he was deep into writing a novel about a poet who worked at Goldman Sachs. Although the main character had Pakistani roots, the story line had little to do with Pakistan, or Islam — Akhtar wasn’t ready yet to explore his heritage. Instead he strove to create a generic exploration of a man’s inner life — a tale, he was certain, was destined to be the next Great American Novel. “I was convinced of that, without any irony,” he says. He completed the novel after six years and soon had to admit its failure. No publisher, no literary agent was interested. Even his friends panned it. “It was just not me,” he recalls. “I thought I was writing what I knew, but I wasn’t.”

that might explain the heavy-handed use of stereotypes in his present work. i understand that akhtar adds much more complexity and nuance to the situations and characters he creates but he’s decided to remain within certain parameters of what constitutes the accepted outside view of the american muslim experience. he made the point last night that as a stereotyped minority, we cannot continue to define ourselves in opposition to anti-muslim propaganda. i couldn’t agree more. i long to break out of that box, that suffocating framework. however, embracing anti-muslim propaganda, albeit with liberal doses of psycho-analysis and some social commentary, is hardly the best way to be free to define ourselves outside of the racist colonial frame of reference where we are expected to exist.

akhtar read from his book “american dervish”. i enjoyed the first section he read which described how spirituality once awakened can elevate day-to-day, pedestrian life to incredible levels of vividness, akin to a mystical experience. the second piece he read from the book was a conversation between a mother and son. he read the pakistani immigrant matriarch’s lines with a pakistani accent. i wanted to tell him he sounded like my kids, whose rendition of a south asian accent is completely in line with hank azaria’s apu (on the simpsons). it made it impossible for me to focus on what the woman was actually saying. her cartoonishness became overwhelming. however, what she said was important. she told her son that jewish men, unlike muslim men, know how to respect women and this was why she was raising him like a jew. this last line was certainly expected to have a comedic effect and it elicited laughter from the audience but within the context of the brutal, misogynistic muslim man oppressing his wife, it had more resonance than the casual witticism it’s supposed to embody.

here’s more from akhtar’s broadway play “disgraced”:

“Islam comes from the desert,” [the Muslim protagonist] says. “From a group of tough-minded, tough-living people who saw life as something hard and relentless. Something to be suffered.” And he speaks admiringly of the other desert-based tradition. “Jews reacted to the situation differently,” he continues. “They turned it over, and over, and over. I mean look at the Talmud. They’re looking at things from a hundred different angles, trying to negotiate with it, make it easier, more livable… It’s not what Muslims do. Muslims don’t think about it. They submit.” But as he’s further agitated, and further drunk, he also admits that he cannot escape his strict Muslim upbringing. “Even if you’re one of those lapsed Muslims sipping your after-dinner scotch alongside your beautiful white American wife and watching the news and seeing folks in the Middle East dying for values you were taught were purer, and stricter, and truer,” he says, “you can’t help but feel just a little a bit of pride.” As he did, he confesses, on September 11. Horrified, he says, but a little bit proud. […] But as much as Ayad’s terrific play is a scarily heightened portrait of the challenges of being an upwardly mobile Muslim-American in our current world, it also raises powerful questions for anyone who could be accused of having a dual loyalty.

from “the who and the what”:

“She has more power over you than she really wants,” Afzal says to Eli, accusing him of failing to treat his wife as a Muslim husband should. … And then, in a line that Mr. White [Afzal] delivers with a chilling casualness, he adds, “And she won’t be happy until you break her, son. She needs you to take it on, man.”

i wonder what the reaction to akhtar’s work would have been if he hadn’t been a muslim. i have a suspicion that we would understand his oeuvre quite differently. although i feel strongly that akhtar benefits from his native informant status, he made it quite clear last night that he doesn’t have double consciousness. he’s just american.

The funny thing is, I don’t feel like I’m writing about Muslim American life,” Akhtar explains. “I feel like I’m writing about American life.”

Akhtar acknowledges that Muslims face an especially precarious place in American society in the aftermath of Sept. 11. In the shadow of surveillance, profiling and doubt, many Muslim artists have been inspired to explore identity in their work. But Akhtar says his characters are also facing a more universal dilemma.

“The process of becoming American has to do with rupture and renewal — rupture from the Old World, renewal of the self in a new world. That self-creative capacity is what it means to be American in many ways, and I think that part of that rupture is the capacity to make fun of yourself and the capacity to criticize yourself.”

i am all for self-criticism. i am all for flawed characters with depth and complexity. i am just looking for something more than the muslim terrorist/wife beater/religious fanatic. perhaps akhtar could turn to his own life and the society he moves in for inspiration. he was born in NYC and raised in milwaukee, both his parents are physicians, he is a graduate of brown and columbia universities, he studied acting in italy with jerzy grotowski, he lives in NYC where he has taught acting along with andre gregory (my dinner with andre). his own life experience as a pakistani-american muslim might be harder to sell to the mainstream but it might sparkle with the kind of originality and truth that would make him an important, authentic voice in american culture. i’ll continue to wait for that play.

KILL THE MESSENGER

watched “kill the messenger” last night. it’s an incredibly important film based on the life and work of gary webb, an american journalist who wrote the 1996 dark alliance series of articles (about CIA involvement in cocaine trafficking in the US). the articles were written for the san jose mercury news and later published collectively as a book. i wasn’t surprised by the fact that drug trafficking was used to finance an illegal war in nicaragua (against people who wanted to reform their govt and ensure free elections), that the money for this illegal war was raised by selling crack cocaine in impoverished black neighborhoods here in the US, that when the story came out the govt used its private propaganda arm (the NYT and washington post among other venerable media institutions) to “controversalize” gary webb and shift the focus on him rather than his work, and that webb could not work as a journalist after this process of delegitimization was successfully carried out. i know that govts lie, that power corrupts, and that the CIA has damaged the world in ways that we are just beginning to understand. i know that the war on drugs is as dark and dodgy as the war on terror. i know that investigative journalists (who don’t just quote govt officials or ask the CIA to proofread their work) put themselves in great danger when shining a light on govt malfeasance of this scale. the thing that took me off guard was one of the last lines in the film. gary webb died in 2004. he was 49 years old. he was found with *two* gunshot wounds to the head. it was deemed a “suicide” and that’s what we’re still told. since when is a human being able to shoot themselves in the head twice? seriously. i guess the suspension of disbelief doesn’t apply only to magic acts or coleridge’s fantastical tales.

more info on gary webb’s story at democracy now!

1907-1915: Russia Before the Revolution, in Color

i love these photographs, not least because of their gorgeousness, but also because they document (in a v real “photographic” way) the ethnic and cultural syncretism which defines the human race. it’s the overlap and magnificent blending of different beliefs and traditions which have built and transformed human civilization over thousands of years. check it out.

…

Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (1863–1944) became photographically renowned in Russia for a color portrait of Leo Tolstoy. It was this fame that, in 1909, brought him to the attention of Tsar Nicholas II. Prokudin-Gorsky’s subsequent meeting with the tsar and the tsar’s family was to be the pivotal moment in his life: The tsar provided both the funding and the authority for Prokudin-Gorsky to carry out what he would later describe as his life’s work. For most of the following decade, using a specially adapted railroad car as a darkroom, Prokudin-Gorsky traversed the length and breadth of the Russian Empire, recording what he saw in more than 10,000 full-color photographs. More here.

diaghilesque in rochester

sept 26, 2014: “diaghilesque” (part of fringe fest at geva theatre) showcases gems of diaghilev’s ballet russe by giving them a post modern/burlesque treatment. i have to think more on my reaction to the show. yes, there were completely naked dancers, lots of uncensored vulgar sex talk, transgenderism, and some beautiful ballet, but i’m not sure it made a long-lasting impression on me. it did make me think about nakedness, the human body, art and eroticism but when it comes to evaluating the show itself i think i lean more towards gimmicky rather than high art. maybe high art is not even what ny-based kinetic architecture dance theatre is going for. it’s definitely fringe. my favorite piece was scheherazade in which the female dancers were clothed in glittery, extremely sheer fabric. it made them look ethereal. it was the first time i noticed their faces. they danced most beautifully.

From the Democrat & Chronicle: In the early 20th century, there was no figure more influential in the world of dance than the legendary impresario Sergei Diaghilev, whose company Ballets Russes set the tone of modern dance for years to come with works choreographed by such artists as Michel Fokine and Vaslav Nijinsky, with original music by the likes of Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky and others.

On Thursday, September 25, transgender dancer and choreographer Arrie Fae Davidson led her small troupe of dancers comprising the KineticArchitecture Dance Theatre in Diaghilesque, a 21st-century recontextualization of these seminal and storied ballets in the second of a four-night run at Geva Theatre as part of the 2014 First Niagara Rochester Fringe Festival.

This reimagining by Davidson–who is sometimes referred to as Faux Pas le Fae–features a veritable mélange of styles in which classical ballet technique and abstract contemporary movement commingle together with the twin spirits of burlesque and performance art. At the outset, six dancers converged on the stage wearing nothing but white, button-down dress shirts and black masks with protruding beaks, à la Pulcinella of commedia dell’arte lore. Davidson then proceeded to welcome the audience–“ladies and gentlemen in all manners of gender”–briefly cataloging the variations of nudity one could expect during the dance vignettes that were to follow.

And while the pervading mood of the evening was one of mischievous play–a tongue-in-cheek ode of optimism to self-expression and liberated sexual and gender identities–it was always grounded in the experiential knowledge that such freedom often comes only after intense struggle.

This was especially apparent during Davidson’s own solo interpretation of “The Dying Swan,” a role originally created for and performed by Ballets Russes dancer Anna Pavlova. Davidson prefaced this melancholic yet triumphant performance with a moving testimonial detailing times in which her transgender identity was met with opposition from societal conventions and people espousing “gender norms.” For the artist, these moments of harsh reality were analogous to dying, but it seemed that the dance itself signaled a kind of rebirth.

Later on in the evening, two topless “Firebirds” engaged in a sensual pas de deux, initially accompanied by Stravinsky’s original ballet score before accumulating sound clips of Johnny Cash’s “Ring of Fire,” The Doors’ “Light My Fire,” and other ubiquitous pop culture references piled on top of one another with a cacophony that was made all the more poignant in contrast to the intimate dance combining softness, strength, and emotional chemistry. In this selection, as well as in the company’s truncated version of “The Rite of Spring,” music editor Mark Schaffer’s keen ear for compelling mashups played a significant role in the communicative power of the dance.

Taking liberties with Fokine’s ballet Les Syphides, in which a poet encounters ethereal spirits of the air known as sylphs, Davidson and company presented a satirical yet serious-minded pantomime depicting an unhealthy sexual relationship characterized by deceit and abuse, of which the emotional and psychological aftermath was articulated beautifully in a solo by dancer Koryn Wicks.

As mentioned in the festival’s promotional materials, due to the performance’s consistent rejection of clothing and its frank handling of the subject matter, Diaghilesque is only suitable for mature festival-goers. That said, it is important to note that KinectArchitecture succeeds in making the nudity less about titillation and much more about establishing a clear conduit between body and emotion. It was as if the dancer’s inner psychological workings were projected in the movements.

And though a reordering of the individual pieces may have resulted in a more compelling dramatic arc–particularly in the case of a well-executed, but anti-climatic closer in “Le Spectre de la Rose”–Diaghilesque is substantive yet frisky art, provocative entertainment with heart.

Colonial State of America

JEREMY GANTZ: The idea of the United States as a peaceful democracy at heart, occasionally pulled into overseas wars, is a comforting verse in the national gospel. It’s part of the origin story told in high school textbooks: A fledgling nation threw off the yoke of British colonial rule and settled the West to become the world’s indispensable democratic nation. Sporadic imperial fits notwithstanding (e.g., the invasions of the Philippines, Vietnam, Iraq), the soul of America “goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy,” as John Quincy Adams once said. In An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Beacon Press), Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz dismisses this story as “patriotic cant”—a piety recited by President Obama and his predecessors to cover up the country’s violent colonial DNA. A retired California State University professor who is part Native American, Dunbar-Ortiz served as an expert witness for American Indian Movement activists put on trial following the deadly 1973 protest at Wounded Knee.

Culminating her nearly half-century career as an activist-academic dedicated to justice for Native people, her concise and disturbing new book dismantles culture national myths to reveal the country’s true foundation: a land grab that required the government-sponsored erasure of millions of indigenous people. Before the start of European colonization, an estimated 15 million Native people lived in what is now the United States. Their descendants number 3 million today, spread across 500 different federally recognized nations. A lack of immunity to European viruses accounts for much of the devastation, but not all. Rebuking the trope that Indians were doomed to die from epidemic diseases, Dunbar-Ortiz writes: “If disease could have done the job, it is not clear why the European colonizers in America found it necessary to carry out unrelenting wars against Indigenous communities in order to gain every inch of land they took from them.” More here.