‘This is a moment for more Americans to study the transnational connections of policing and state violence in an effort to forge a common anti-racist, anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggle. We need more global protests as well as gatherings to devise ways to eradicate the scourge of state violence that disproportionately affects BIPOC throughout the world. As scholar-activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore has said, “The abolitionist future … has to be internationalist, because that is the only way that we’ll stop drawing the borders that regularize between and among people.”

Over the last two weeks, protesters abroad are saying the names of those who have fallen to state violence in the U.S. Throngs of multi-ethnic, multi-racial and multinational people have also sought to topple the symbols of enslavement, colonization and imperialism. We in the United States should be saying Regis Korchinski-Paquet’s and Eyad al-Hallaq’s names and amplifying the efforts of people to destroy the vestiges of oppression. The more we engage in these actions and expressions of solidarity, the closer we get to realizing that another world — free of state violence — is possible.‘ More here.

Category: politics

‘Impossible Documents’ — How An Enslaved Muslim Scholar Illuminates Southern Identity

one of the most fascinating conversations i’ve listened to in a while. about islam and slavery, islam in america, christian hegemony and slavery, a counter narrative offered in/by the arabic language and the only known writing by an enslaved human while they were still in bondage. enriches this moment that we are in by revealing layer upon layer of historical complexity and intersections.

‘In the 1700s, approximately 5% of the pre-colonial United States was Muslim. Most of them were enslaved, and one of the foundational figures of early American Islam lived in North Carolina. Omar ibn Said has confounded scholars and translators for more than a century.

An educated scholar from an aristocratic family, Said was enslaved and brought to the port of Charleston in 1807 from his homelands in the Futa Toro region of modern-day Senegal. His autobiography is written in Arabic with a Southern accent and includes references to West African locations and Sufi literature. In it, Said attacked his enslavers and the conditions of the American South while also illuminating his struggle to overcome the psychological imprisonment of slavery. He wrote because he needed to.’ Listen here.

What Did Cedric Robinson Mean by Racial Capitalism?

So what did Robinson mean by “racial capitalism”? Building on the work of another forgotten black radical intellectual, sociologist Oliver Cox, Robinson challenged the Marxist idea that capitalism was a revolutionary negation of feudalism. Instead capitalism emerged within the feudal order and flowered in the cultural soil of a Western civilization already thoroughly infused with racialism. Capitalism and racism, in other words, did not break from the old order but rather evolved from it to produce a modern world system of “racial capitalism” dependent on slavery, violence, imperialism, and genocide. Capitalism was “racial” not because of some conspiracy to divide workers or justify slavery and dispossession, but because racialism had already permeated Western feudal society. The first European proletarians were racial subjects (Irish, Jews, Roma or Gypsies, Slavs, etc.) and they were victims of dispossession (enclosure), colonialism, and slavery within Europe. Indeed, Robinson suggested that racialization within Europe was very much a colonial process involving invasion, settlement, expropriation, and racial hierarchy. Insisting that modern European nationalism was completely bound up with racialist myths, he reminds us that the ideology of Herrenvolk (governance by an ethnic majority) that drove German colonization of central Europe and “Slavic” territories “explained the inevitability and the naturalness of the domination of some Europeans by other Europeans.” To acknowledge this is not to diminish anti-black racism or African slavery, but rather to recognize that capitalism was not the great modernizer giving birth to the European proletariat as a universal subject, and the “tendency of European civilization through capitalism was thus not to homogenize but to differentiate—to exaggerate regional, subcultural, and dialectical differences into ‘racial’ ones.” More here.

paul gilroy In conversation with Ruth Wilson Gilmore

Paul Gilroy: I don’t know if you’ve come across the things that Achille Mbembe has been writing from South Africa in the last few weeks, but he has been talking a lot about what he calls ‘the Universal Right to Breathe’, and I was very struck by that, I haven’t had a chance to discuss it with him yet at length but I think this whole question of a more universalistic orientation – can I even say that I don’t even know if that’s the right word – I suppose I would want to say not universalistic because that sense of big, a common – a common vulnerability, a common sense of humanity. I mean maybe some of the things that are going on in this mobilisation, some of the things we’re learning from Covid, and here’s my utopian hat going over my head, maybe they speak to the possibility of a different future for the human than the one that we feared is coming towards us. I mean, am I going too far?

Ruth Wilson Gilmore: Oh I hope not, I hope you’re not going too far and in fact one thing I’ve been thinking about a lot lately is how there’s a bit of a divergence these last few weeks between what you just described – a different future for the human – as against a path that worries me very much which is one that is in the recapitulating a certain kind of apartheid thinking in the name of undoing the effects of apartheid in the world scale. And by that I mean the tendency that’s got me worried is the one in which people are insisting that only certain demographics of people are authorised to speak about – speak from or speak against – certain kinds of horrors, and other people have already existing assignable jobs based on their demographic – let’s call it a caste system – that they’re supposed to do, so white people are supposed to fix white supremacy and so on and so forth. That path, which is actually a pretty strong path, doesn’t excite me. I’m 70 years old, I’m done with it, I’ve been done with it a very long time. The path however which some of the young Black Lives Matter people named 5 years ago in that year of uprising in the United States, after the death of Mike Brown and Freddie Gray and so forth, the one in which they said quite simply ‘when black lives matter everybody lives better’ – that’s the path that is of interest to me. So, I for one would like very much, I endorse completely, reinvigorating the notion of universal; I don’t know what to call it, if the word universal is the problem that people stumble over. More here.

You can listen here.

Angela Davis on Abolition, Calls to Defund Police, Toppled Racist Statues & Voting in 2020 Election

Angela Davis: I want us to see feminism not only as addressing issues of gender, but rather as a methodological approach of understanding the intersectionality of struggles and issues. Abolition feminism counters carceral feminism, which has unfortunately assumed that issues such as violence against women can be effectively addressed by using police force, by using imprisonment as a solution. And of course we know that Joseph Biden, in 1994, who claims that the Violence Against Women Act was such an important moment in his career — the Violence Against Women Act was couched within the 1994 Crime Act, the Clinton Crime Act.

And what we’re calling for is a process of decriminalization, not — recognizing that threats to safety, threats to security, come not primarily from what is defined as crime, but rather from the failure of institutions in our country to address issues of health, issues of violence, education, etc. So, abolition is really about rethinking the kind of future we want, the social future, the economic future, the political future. It’s about revolution, I would argue.

[…] I think that these assaults on statues represent an attempt to begin to think through what we have to do to bring down institutions and reenvision them, reorganize them, create new institutions that can attend to the needs of all people. More here.

An Astonishing New Cancer Memoir Brings Radical Politics to the Genre

Anne Boyer: One of the things that happen when you get sick, especially if you particularly like to read, is that you get all these books in the mail. What I noticed was this incredible ideological onslaught treating everything as an individual experience as opposed to a collective, political one. All those struggles get put in these utterly rigid narrative containers in which we’re supposed to follow a sentimental heroine through the harrowing journey. It reproduces a sort of grim pleasure of watching women suffer. Cancer narratives are so, so burdened by this weight.

I think part of [the difference with The Undying] has to do with my being a Marxist feminist. That’s a political awakening from much earlier in my life. With economic troubles or troubles with sexual harassment or other kinds of gendered obstacles and violence, I decided that I could either see myself as loathsome and undeserving or I could expand beyond myself. I could not resolve to hate myself when I was young and these things were happening to me, so I began to reach out for a way to think about the world that didn’t require me to submit to the way that I was being treated inside of it. More here.

INSTRUMENTS OF MEMORY IG TAKEOVER – 5

Repost from @instrumentsofmemory:

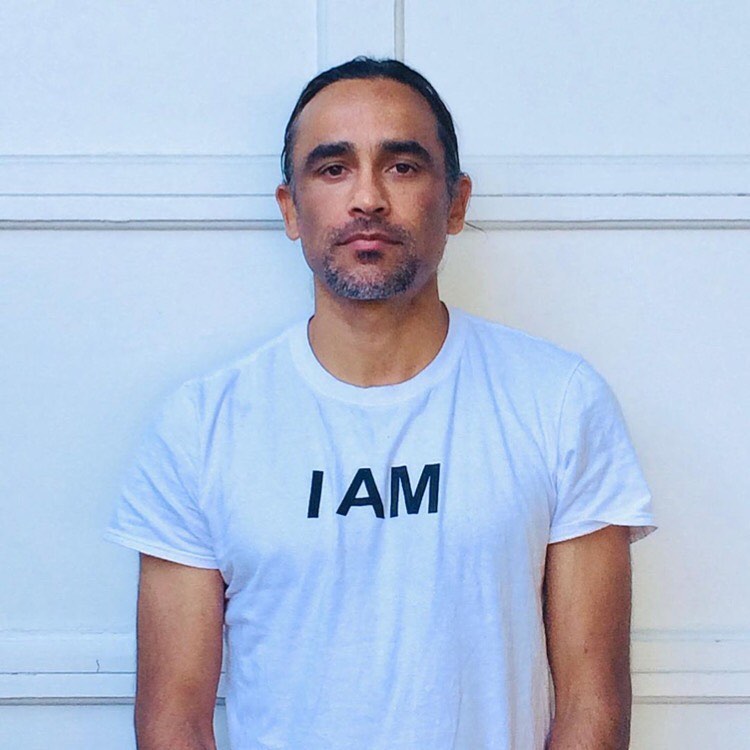

As I end my Instruments of Memory IG takeover, I would like to thank my team. Filmmaking is all about teamwork and I am lucky to have collaborated with some exceptionally gifted artists and human beings on ‘The Injured Body.’

I will continue to edit and transcribe interviews and I will be posting images and thoughts on my IG. Please follow me @mara__ahmed to stay in touch and learn more about the film. At this historic moment in our country (and around the world), let’s vow to eradicate racism in our families and communities, but also within ourselves. A better world is possible.

Thank you once again to Instruments of Memory and Claudia Pretelin for this wonderful opportunity.

Photographs of Rajesh Barnabas [Cinematography], Mariko Yamada [Dance Choreography], Erica Jae [Photography], Tom Davis [Musical Score], Imani Sewell [Soprano], Darien Lamen [Sound Design, Photo by Aaron Winters] and Jesus Duprey [Additional Camera]

(see more photos on IG)

thinking in terms of work

friends, i am overjoyed to see a much larger, broader contingent of people embracing #BLM and anti-racism language. the word ‘performative’ has been bouncing around but i think that there is a sincere wish for knowledge and participation, and i applaud those who are brave enough to ask for direction.

it’s stunning to me that ‘modern life’ (in what we like to call the ‘first world’) is so terribly fragmented, that the grotesque inequities in this country are just now becoming visible to all.

i also hope that there will be a second wave of awakening and reckoning in which americans will recognize the violence and horror they visit on the rest of the world. the systems and hierarchies we are fighting here are worldwide. we cannot abolish the police, without abolishing the brutal occupation and ongoing annexation of palestine. the two are inextricably tied together.

as far as joining the movement and making a dent, it might help to think in terms of work. posting on social media is good, but what can we contribute in terms of work. the work can be community-oriented but it can also be internal. how do we eradicate racism (as well as sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, anti-semitism, islamophobia, etc) within ourselves and in our closest circle of friends. what should be our strategies when we encounter bigotry in our families? how do we change the DNA of our own thoughts and worldview?

work requires time and energy, it exacts a certain cost. this is what’s needed right now.

INSTRUMENTS OF MEMORY IG TAKEOVER – 4

Repost from @instrumentsofmemory:

From Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric:

‘Perhaps each sigh is drawn into existence to pull in, pull under, who knows; truth be told, you could no more control those sighs than that which brings the sighs about.

//

The sigh is the pathway to breath; it allows breathing. That’s just self-preservation. No one fabricates that. You sit down, you sigh. You stand up, you sigh. The sighing is a worrying exhale of an ache. You wouldn’t call it an illness; still it is not the iteration of a free being.’

‘The Injured Body’ weaves together an alternative narrative strand told through dance and movement, mostly choreographed by Mariko Yamada. Since prejudice is largely a matter of reading bodies in particular ways and racism is received by and carried in the body, dance is the perfect medium to underline and explore the personal stories shared in the film.

Film stills with Mariko Yamada, Joyce Edwards, Nanako Horikawa, Andrea Vazquez-Aguirre Kaufmann, Cloria Iampretty, Sraddha Prativadi, Sejal Shah, María José Rodríguez-Torrado, Alaina Olivieri, Rosalie M. Jones, and Andrew David

Photography by Mara Ahmed @mara__ahmed

INSTRUMENTS OF MEMORY IG TAKEOVER – 3

Repost from @instrumentsofmemory:

Claudia Rankine in ‘Citizen: An American Lyric’:

‘Yes, and the body has memory. The physical carriage hauls more than its weight. The body is a threshold across which each objectionable call passes into consciousness—all the unintimidated, unblinking, and unflappable resilience does not erase the moments lived through…’

The women interviewed for ‘The Injured Body’ share stories of micro-aggressions and parse their cumulative effect on the mind and body, but they also describe their visions for a world without racism or violence. This is a crucial part of the film, as imagining a better world is an important step towards achieving it.

In order to include a diversity of voices, we interviewed women one-on-one but also in groups, where the conversation was more fluid and informal. Here are some of our panelists.

Luticha A Doucette, Marcella Davis, Khadija Mehter, Muna Lisa, Yogi Indrani, Pamela Kim, Tianna Mañón, Mercedes Phelan, and Erica Bryant

All photography by Erica Jae (see all photos on IG)

let’s build with integrity

friends, i know that people are sharing posts quickly and passionately in order to get information out there and support the uprising, but could we pls use the appropriate attributions? someone put the effort into compiling a list, creating a resource guide, or formulating their analysis. let’s give credit to those who did the work. most organizers and artists are ok with reposts (it’s about the collective not the individual) but we can build together with respect and integrity.

INSTRUMENTS OF MEMORY IG TAKEOVER – 2

Repost from @instrumentsofmemory:

My new documentary, The Injured Body, examines racism though the lens of micro-aggressions: slights, slips of the tongue, or intentional offenses that accumulate over a lifetime and impede a person’s ability to function and thrive in the world.

I chose to approach racism by focusing on micro-aggressions because of two reasons. Firstly, as Claudia Rankine explains, we seem to understand structural racism somewhat, but are baffled by racism coming from friends. It is disorienting because it is unmarked. ‘The Injured Body’ hopes to home in on the language needed to ‘mark the unmarked.’ Secondly, personal stories lend themselves to filmmaking because they can help create intimacy and trust, and lay the groundwork for a paradigm shift.

The film spotlights the voices of women of color not only because their stories are misrepresented and frequently ignored by mainstream media, but also because they operate at the intersection of multiple forms of oppression and can articulate the complexity of those experiences. Their testimony and analysis can help broaden traditional understandings of feminism as well as anti-racism work.

Film stills/photographs of Ayni Ali, Amanda Chestnut , Sady Fischer, Lu LutonyaRachel Highsmith, Lauren Jemison, Elizabeth Nicolas, Greta Aiyu Niu, and Tonya Noel

Ayni Ali’s photograph by Arleen Thaler, all other photography by Erica Jae (pls see on IG)

instruments of memory IG takeover – 1

Repost from @instrumentsofmemory:

Hey you all. My name is Mara Ahmed. I am an activist filmmaker and multimedia artist based in Long Island, New York. I’ve lived and gone to school on three different continents. I am many places and cultures but I identify with and am interested in those who end up on the ‘wrong’ side of borders. And history.

I’m working on my fourth film (getting ready to edit) and will be posting mostly about that project – ideas that coalesced into the film and stills from our shoots. Thanks to @instrumentsofmemory and @claudia_pretelin for letting me take over this IG.

My new documentary is called ‘The Injured Body: A Film about Racism in America.’ It’s inspired by Claudia Rankine’s book ‘Citizen: An American Lyric.’ ‘Rankine says that American life is made of moments when race gets us “by the throat.” Only some are nationally noted tragedies.’ Most others are minimized as ‘microaggressions,’ yet they damage deeply.

My favorite lines from the book:

You are not sick, you are injured—

you ache for the rest of life.

How to care for the injured body,

the kind of body that can’t hold

the content it is living?

And where is the safest place when that place

must be someplace other than in the body?

maraahmed #instumentsofmemory #instrumentsofmemorytakeover

activism #art #film #documentary #racism #america #claudiarankine #citizen #microaggressions #theinjuredbody #neelumfilms

protests in brussels

brussels today. in solidarity with #BLM and a mobilization of europe’s own anti-racist, anti-colonial struggles. let’s never forget this larger context. incredible.

Slavery and the Origins of the American Police State

#AbolishPolice

Ben Fountain: Control of this new (enslaved) labor force would be key; mutiny was the great fear. By the early 1700s, a comprehensive system of racially directed law enforcement was well on its way to being fully developed. This was, in fact, the first systematic form of policing in the land that would become the United States. The northeast colonies relied on the informal “night-watch” system of volunteer policing and on private security to protect commercial property. In the southern colonies, policing’s origins were rooted in the slave economy and the radically racialized social order that invented “whiteness” as the ultimate boundary. “Whites,” no matter how poor or low, could not be held in slavery. “Blacks” could be enslaved by anyone—whites, free blacks, and people of mixed race.

The distinction—and the economic order that created it—was maintained by a legally sanctioned system of surveillance, intimidation, and brute force whose purpose was the control of blacks. Slave patrols, or paddyrollers, were the chief enforcers of this system; groups of armed, mounted whites who rode at night among the plantations and settlements of their assigned “beats”—the word originated with the patrols—seeking out runaway slaves, unsanctioned gatherings, weapons, contraband, and generally any sign of potential revolt.

[…] The system continued largely intact after Emancipation and the defeat of the Confederacy. Legally sanctioned slave patrols were replaced by night-riding vigilantes like the Ku Klux Klan, whose white robes, flaming torches, and pseudo-ghost talk were intended for maximum terrorizing effect. Lynching and shooting took place alongside the more traditional punishments of beating and whipping; blacks’ economic value as slaves had evaporated, and with it the constraints on lethal force that had offered some measure of protection under the old system.

White supremacy continued as the dominant reality for the next hundred years, a social and psychological reality maintained by terror, surveillance, and the letter of the law. Its power was such that even the New Deal—the most profound reordering of American society since the Civil War—left white supremacy intact. Twenty-six lynchings were recorded in Southern states in 1933. An antilynching bill was defeated in Congress in 1935.

[…] We don’t have to know the particulars of history in order to live it in our bones. Sometimes history arrives as a sense of the uncanny, the peculiar weight of certain words and acts, a suffusion of dreadful power. We might suppose the pass system is long gone, but there it is in stop-and-frisk, in racial profiling, in the reflexive fear and violence of our own time. More here.