Fatenah, which tells the fictional story of a young seamstress from a Gaza refugee camp, is the first commercial Palestinian animation film ever made. The heart-wrenching tale follows Fatenah’s pain and humiliation as she struggles to leave Gaza for treatment after finding few Palestinian doctors willing to help. Full article.

Category: art

“It Isn’t Nice” by Malvina Reynolds

It isn’t nice to block the doorway,

It isn’t nice to go to jail,

There are nicer ways to do it,

But the nice ways always fail.

It isn’t nice, it isn’t nice,

You told us once, you told us twice,

But if that is Freedom’s price,

We don’t mind.

It isn’t nice to carry banners

Or to sit in on the floor,

Or to shout our cry of Freedom

At the hotel and the store.

It isn’t nice, it isn’t nice,

You told us once, you told us twice,

But if that is Freedom’s price,

We don’t mind.

We have tried negotiations

And the three-man picket line

Mr. Charlie didn’t see us

And he might as well be blind.

Now our new ways aren’t nice

When we deal with men of ice,

But if that is Freedom’s price,

We don’t mind.

How about those years of lynchings

And the shot in Evers’ back?

Did you say it wasn’t proper,

Did you stand upon the track?

You were quiet just like mice,

Now you say we aren’t nice,

And if that is Freedom’s price,

We don’t mind.

It isn’t nice to block the doorway,

It isn’t nice to go to jail,

There are nicer ways to do it

But the nice ways always fail.

It isn’t nice, it isn’t nice,

But thanks for your advice,

Cause if that is Freedom’s price,

We don’t mind.

sept 13: celebration party for publication of “paternity”

my friend sue baruch is the proud author of paternity, out in paperback now! buy it here.

“Joel Berger’s charmed life is fast slipping away. Determined to father a child before he dies, Joel makes one desperate appeal to the women of his macrobiotic dinner group for help. Soon he is surrounded by a colorful cast of female characters, including his iron-willed yet oddly endearing mother, Sylvia. You’ll laugh and cry along with the Bergers as the story of their patchwork family begins to unfold, taking some deliciously unexpected turns along the way.”

heddy honigmann’s “forever” – art and immortality

i believe patterns exist everywhere – in life, in art, in relationships. lovely patterns, ever-repeating, delicately wrought like lacework – patterns which crave balance and symmetry.

lately my conversations with friends have been about art – art as a radical change agent, a transformative force that can show us possibilities without reiterating the constraints of our thinking and therefore our being; art as a new language that bypasses the rigid, state-defined categories of religion, history, politics and culture; art as “the crucible within which our evolving notions of what it means to be fully human are put to the test.”[1]

at the same time i have had discussions about the necessity to see each individual as unique – unfettered by perceptions related to race, ethnicity, nationality or religion; every human being a rich and complex amalgam of thoughts, emotions and physicality, with the potential for both good and evil.

it was in this state of mind that i saw “forever.” shot mostly at the père lachaise cemetery in paris, “forever” is a truly captivating documentary. it’s directed by heddy honigmann, a citizen of the world: her parents were holocaust survivors who immigrated to peru, she studied filmmaking in rome and now works in the netherlands. honigmann is interested in exile, loss and nostalgia. maybe that’s why i was strongly drawn to the emotive pull in her work. she is an innovator. when she begins to sketch a documentary idea, she imagines certain characters and it is up to her research staff to discover them in real life. thus, the line between fiction and non-fiction becomes blurred and the documentary form, already an arresting medium on account of its spontaneity, is exalted to the perfection of true artwork.

“forever” is an ode to art, artists and the people they inspire. père lachaise is famous for the many celebrities buried there – jim morrison, chopin, marcel proust, oscar wilde, ingres, modigliani, sadegh hedayat, yves montand, simone signoret, maria callas, george méliès. however, the real stars of the film are regular people who visit these graves (and those of loved ones buried side by side with them), spruce up tombstones, and tell stories. each story is beautiful, profound and unique, yet all the more human in its reverberations.

an old woman who visits her husband’s grave talks about escaping franco’s spain. she saw prisoners being executed in cold blood and lost her faith in god when a priest walked in to finish off survivors with a final gunshot.

a man pays his respects to sadegh hedayat. he’s a taxi driver but his passion is music, traditional persian music. it’s an important release for him, a way to stay connected to his culture, the only way to survive a life of exile. honigmann prods him gently to sing for her. he hesitates, demurs then obliges. he sings a poem by hafez.

this instant hook into the past via language is something i know intimately. there is my three decades long love affair with the french language. as i lost fluency – my ability to dream in french – my sense of grief was acute. with urdu it’s another kind of relationship. i have never had an urdu vocabulary comparable to french but it’s the language i feel at “home” in – where the discrepancy between my inner life and the rest of the world disappears and there is a level of unified calmness, a certain truth. after many years of living in a pakistani cultural void, when i listened to a faiz ahmed faiz poem sung by the inimitable noor jehan, a poem about how you cannot insulate yourself with romantic love once you’ve been exposed to humanity’s terrible suffering (“there are other sorrows in this world, comforts other than love. don’t ask me, my love, for that love again”), i was astonished by my own emotion.

talking about remembering the past, one of the most visited graves in père lachaise is that of marcel proust. stephane heuet, an ardent proust admirer, explains how he was so moved by the striking visuality of “a la recherche du temps perdu” that he decided to render it into a graphic novel. he sees proust primarily as a painter. prompted by honigmann, he attempts to explain the mystique of the madeleine. he differentiates between voluntary and involuntary memory – exerting effort to recall the past vs being spontaneously transported to another time and place. the madeleine acts as a trigger and suddenly proust is enveloped by his past, as vivid and palpable as when he was a child. heuet explains how this concept endows us with immortality. if all the places and times we have ever experienced reside simultaneously within us then we become a conduit for eternity. he goes on to talk about proust’s pursuit of happiness – in relationships, in possessions, in society – and his ultimate discovery that happiness can only be found in art.

a solemn-looking man talks about modigliani’s love of the human face; the way he uses light and color to abstract and imbue with emotion. along the way we find out that he’s an embalmer. he takes his work seriously. he feels responsible. when the family of the deceased takes a final look at their loved one, they should be able to remember them as they were in life.

a guide reminisces about his childhood visits to the cemetery with his grandfather. how death used to be a part of life – funeral processions would pass through the city center. he tells a lovely story about a young woman he once knew who changed him forever. in a moment of sharp clarity, his future seemed to spread out before him and he knew that he would never know boredom, for he would always have access to art.

an older woman tells a story of true, all-consuming love. her husband of two months, the love of her life, a much younger man whom she found in her fifties, killed by a bee sting. no, he had no idea he was allergic. he had lived in africa for many years. he could never have imagined. her pain is still keen. it’s hard she says. it’s hard when it happens to you.

throughout the film there are brief musical interludes. they sometimes underscore the stories being told but there is a consistent presence – chopin’s music. a japanese young woman who moved to paris to learn to play chopin the right way, talks about her father’s untimely death. he loved chopin. for her, playing chopin’s music is a mystical experience, a way to commune with her dead father. the film starts and ends with her and chopin is a grand finale to a small, sensitive film about exalted, universal themes.

thanks to my friends: terry for making me watch “forever” and damien and christopher for our discussions about art and humanity.

[1] mark slouka, “dehumanized – when math and science rule the school”, harper’s, sept 2009

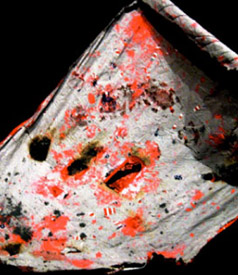

Darat al Funun – Return of the Soul: The Nakba Project by Jane Frere

The Nakbah project was led by Scottish artist Jane Frere. The artwork is a multi-dimensional installation of around 3,000 wax figures. Suspended in the air by clear nylon thread, the figures are positioned on a raked angle across the space, giving the elusion of depth and motion representing the departure of Palestinians in the 1948 exodus. Sound, video and scripted testimonies will escort the figures. Full article.

Art as Resistance

The goal of the Warrior Writers Project is to provide “tools and space for community building, healing and redefinition”. Through writing/artistic workshops that are based on experiences in the military and in Iraq, the veterans unbury their secrets and connect with each other on a personal and artistic level. The writing from the workshops is compiled into books, performances and exhibits that provide a lens into the hearts of people who have a deep and intimate relationship with the Iraq war.” Full article.

John Hanson’s love for Urdu

true – urdu is one of the most beautiful languages of the world ?

“Umeed e Sahar” by LAAL, based on the poem by Faiz Ahmed Faiz

For Pakistani Rockers, A Plugged-In Protest

It’s not uncommon for Pakistanis to sing poetry and use it in political protests. So when Pakistan’s first Communist rock band re-appropriated decades-old verses about hope, its songs became the soundtrack to Pakistan’s lawyers’ movement. Full article.

The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock

t.s. eliot is one of my favorite poets: “His poetry has all the advantages of a highly critical habit of mind,” writes A. Alvarez; “there is a coolness in the midst of involvement; he uses texts exactly for his own purpose; he is not carrie…d away. Hence the completeness and inviolability of the poems.”

Franz Ferdinand – Katherine Kiss Me

love this. sexiest male voice imo…

John Pilger – The books that counter our “training” to make war

In their modern classic Manufacturing Consent: the Political Economy of the Mass Media, Edward S Herman and Noam Chomsky describe how war propaganda in free societies is “filtered” by media organisations, not as conscious “crude intervention, but by the selection of right-thinking personnel and by the editors’ and working journalists’ internalisation of [elite] priorities and definitions of newsworthiness”. Full article.

Harry Patch (In Memory of) – Radiohead

“i am the only one that got through

the others died where ever they fell

it was an ambush

they came up from all sides

give your leaders each a gun and then let them fight it out themselves

i’ve seen devils coming up from the ground

i’ve seen… hell upon this earth

the next will be chemical but they will never learn”

Somali-Canadian Rapper K’naan on Journey from Civil War Refugee to Global Hip-Hop Artist

Piracy in Somalia is something that is fairly new. Since the fall of Siad Barre’s government in 1991, a lot of major Western nations had been bringing their vessels into Somali waters and not only illegally fishing, costing Somalia over $300 million a year in stolen fish, but also dumping nuclear toxic waste. So fishermen, ex-fishers and even ex-coast guards and militiamen got together to hold these criminals at bay. Watch interview.

“Divided selves” by Salman Rushdie (The Guardian, 23 November 2002)

The most precious book I possess is my passport. Like most such bald assertions, this will come across as something of an overstatement. A passport, after all, is a commonplace object.

You probably don’t give a lot of thought to yours most of the time. Important travel document, try not to lose it, terrible photograph, expiry date coming up soonish: in general, a passport requires a relatively modest level of attention and concern. And when, at each end of a journey, you do have to produce it, you expect it to do its stuff without much trouble. Yes, officer, that’s me, you’re right, I do look a bit different with a beard, thank you, officer, you have a nice day too. A passport is no big deal. It’s low-maintenance. It’s just ID.

I’ve been a British citizen since I was 17, so my passport has indeed done its stuff efficiently and unobtrusively for a long time now, but I have never forgotten that all passports do not work in this way. My first – Indian – passport, for example, was a paltry thing. Instead of offering the bearer a general open-sesame to anywhere in the world, it stated in grouchy bureaucratic language that it was only valid for travel to a specified – and distressingly short – list of countries.

On inspection, one quickly discovered that this list excluded almost any country to which one might actually want to go. Bulgaria? Romania? Uganda? North Korea? No problem. The USA? England? Italy? Japan? Sorry, sahib. This document does not entitle you to pass those ports. Permission to visit attractive countries had to be specially applied for and, it was made clear, would not easily be granted.

Foreign exchange was one problem. India was chronically short of it, and reluctant to get any shorter. A bigger problem was that many of the world’s more attractive countries seemed unattracted by the idea of allowing us in. They had apparently formed the puzzling conviction that once we arrived we might not wish to leave. “Travel”, in the happy-go-lucky, pleasure-seeking, interest-pursuing, vacationing western sense, was a luxury we in India were not allowed. We could, if we were lucky, be granted permission to make trips that were absolutely necessary. Or, if unlucky, denied such permission, which was just our tough luck.

In Among the Believers, VS Naipaul’s book about his travels in the Muslim world, a young man who has been driving the author around Pakistan admits that he doesn’t have a passport and, keen to go abroad and see the world, expresses a yearning for one. Naipaul reflects, more than a little caustically, that it’s a shame that the only freedom in which this young fellow appears to be interested is the freedom to leave the country.

When I first read this passage, years ago, I had a strong urge to defend that young man against the celebrated writer’s contempt. In the first place, the desire to get out of Pakistan, even temporarily, is one with which many people will sympathise. In the second and more important place, the thing that the young man wants – freedom of movement across frontiers – is, after all, a thing that Naipaul himself takes for granted, the very thing, in fact, that enables him to write the book in which the criticism is made.

I once spent a day at the immigration barriers at London’s Heathrow airport, watching the treatment of arriving passengers by immigration personnel. It did not amaze me to discover that most of the passengers who had some trouble getting past the control point were not white, but black or Arab-looking.

What was surprising is that there was one factor that overrode blackness or Arab looks. That factor was the possession of an American passport. Produce an American passport, and immigration officers at once become colour blind, and wave you quickly on your way, however suspiciously non-Caucasian your features. To those to whom the world is closed, such openness is greatly to be desired. Those who assume that openness to be theirs by right perhaps value it less. When you have enough air to breathe, you don’t yearn for air. But when breathable air gets to be in short supply, you quickly start noticing how important it is. (Freedom’s like that, too.)

The reason I needed that first Indian passport, limited as its abilities were, was that eight weeks after I was born a new frontier came into being, and my family was cut in half by it. Midnight, August 13-14, 1947: the partition of the Indian subcontinent, and the creation of the new state of Pakistan, took place exactly 24 hours before the independence of the rest of the former British colony.

India’s moment of freedom was delayed on the advice of astrologers, who told Jawaharlal Nehru that the earlier date was star-crossed, and the delay would allow the birth to take place under a more auspicious midnight sky. Astrology has its limitations, however, and the creation of the new frontier ensured that the birth of both nations was hard and bloody.

My own Indian Muslim family was fortunate. None of us was injured or killed in the partition massacres. But all our lives were changed, even the life of a boy of eight weeks and his as-yet-unborn sisters and his extant and future cousins and all our children too. None of us is who we would have been if that line had not stepped across our land.

One of my uncles, my mother’s younger sister’s husband, was a soldier. At the time of independence he was serving as an aide-de-camp to Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, commanding officer of the outgoing British army in India.

Auchinleck, known as “the Auk”, was a brilliant soldier. He had been responsible for the reconstruction of the British Eighth Army in north Africa after its defeats by Erwin Rommel, rebuilding its morale and forging it into a formidable fighting force; but he and Winston Churchill had never liked each other, so Churchill removed him from his African command and packed him off to oversee the sunset of empire in India, allowing his replacement, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, to reap the glory of all Auchinleck’s work by defeating Rommel at El Alamein.

Auchinleck was a rarity among second world war field marshals in that he resisted the temptation of publishing his memoirs, so this is a story that came down to me from my uncle, his ADC, who later became a general in the Pakistani army and for a time a minister in the Pakistani government as well.

My uncle the general told another story, too, which created a ripple of interest when he published his own memoirs late in life. The Auk, he said, had been convinced that he could stop the partition massacres if he were allowed to intervene, and had approached Britain’s prime minister, Clement Attlee, to ask for permission to do so.

Attlee, rightly or wrongly, took the view that the period of British rule in India was over, that Auchinleck was only there in a transitional, consultative capacity, and should therefore do nothing. British troops were not to get involved in this purely Indo-Pakistani crisis. This inaction was the final act of the British in India. What Nehru and Mohammad Ali Jinnah would have felt about a British offer of help is not recorded. It is possible they would not have agreed. It is probable they were never asked. As for the dead, nobody can even agree on how many there were. One hundred thousand? Half a million? We can’t be sure. Nobody was keeping score.

During my childhood my parents, sisters and I would sometimes travel between India and Pakistan – between Bombay and Karachi – always by sea. The steamers plying that route were a pair of old rust-buckets, the Sabarmati and the Sarasvati. The journey was hot and slow, and for mysterious reasons the boats would always stop for hours off the coast of the Rann of Kutch, while unexplained cargoes were ferried on and off: smugglers’ goods, I imagined eagerly, gold, or precious stones. (I was too innocent to think of drugs.)

When we reached Karachi, however, we entered a world far stranger than the smugglers’ marshy, ambiguous Rann. It was always a shock for us Bombay kids, accustomed as we were to the easy cultural openness and diversity of our cosmopolitan home town, to breathe the barren, desert air of Karachi, with its far more closed, blinkered monoculture. Karachi was boring. (This, of course, was before it turned into the gun-law metropolis it has now become, in which the army and police, or those soldiers and policemen who have not been bought off, worry that the city’s criminals may well be better armed than they are. It’s still boring, there’s still nowhere to go and nothing to do, but now it’s frightening as well.) Bombay and Karachi were so close to each other geographically, and my father, like many of his contemporaries, had gone back and forth between them all his life. Then, all of a sudden, after partition, each city became utterly alien to the other.

As I grew older the distance between the two cities increased, as if the borderline created by partition had cut through the landmass of south Asia as a taut wire cuts through a cheese, literally slicing Pakistan away from the landmass of India, so that it could slowly float away across the Arabian Sea, the way the Iberian peninsula floats away from Europe in José Saramago’s novel The Stone Raft.

In my childhood the whole family used to gather, once or twice a year, at my maternal grandparents’ home in Aligarh in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. These family gatherings held us together; but then my grandparents moved to Pakistan, the Aligarh house was lost, the gatherings ended, and the Indian and Pakistani branches of the family began to drift apart. When I met my Pakistani cousins I found, more and more, how unlike one another we had become, how different our basic assumptions were. It became easy to disagree; easier, for the sake of family peace, to hold one’s tongue.

As a writer I’ve always thought myself lucky that, because of the accidents of my family life, I’ve grown up knowing something of both India and Pakistan. I have frequently found myself explaining Pakistani attitudes to Indians and vice versa, arguing against the prejudices that have grown more deeply ingrained on both sides as Pakistan has drifted further and further away across the sea.

I can’t say that my efforts have been blessed with much success, or indeed that I have been an entirely impartial arbiter. I hate the way in which we, Indians and Pakistanis, have become each other’s others, each seeing the other as it were through a glass, darkly, each ascribing to the other the worst motives and the sneakiest natures. I hate it, but in the last analysis I’m on the Indian side.

One of my aunts was living in Karachi, Pakistan, at the time of partition. She was a close friend of the famous Urdu poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911-84). Faiz was the first great writer I ever met, and through his oeuvre and his conversation he provided me with a description of the writer’s job that I accepted fully. Faiz was an exceptional lyric poet, and his many ghazals, set to music, earned him literally millions of admirers, even though these were, often, strangely unromantic, disabused serenades:

Do not ask of me, my love,

that love I once had for you…

How lovely you are still, my love,

but I am helpless too;

for the world has other sorrows than love,

and other pleasures, too.

Do not ask of me, my love,

that love I once had for you.

He loved his country, too, but one of his best poems about it took, with lyrical disenchantment, the point of view of the alienated exile. This poem, translated by Agha Shahid Ali, was put up on posters in the New York subway a couple of years ago, to the delight of all those who love Urdu poetry:

You ask me about that country whose details now escape me,

I don’t remember its geography, nothing of its history.

And should I visit it in memory,

It would be as I would a past lover,

After years, for a night, no longer restless with passion,

With no fear of regret.

I have reached that age when one visits the heart merely as a courtesy.

An uncompromising poet of both romantic and patriotic love, Faiz was also a political figure and a very public writer, taking on the central issues of his time both inside and outside his poetry. This double-sided conception of the writer’s role, part private and part public, part oblique and part direct, would, thanks in large part to the influence of Faiz’s example, become mine as well. I did not share his political convictions, in particular his fondness for the Soviet Union, which gave him the Lenin peace prize in 1963, but I did quite naturally share his vision of what the writer’s job is, or should be.

But all this was many years later. In 1947, Faiz might not have survived the riots that followed partition had it not been for my aunt.

Faiz was not only a communist but an outspoken unbeliever as well. In the days following the birth of a Muslim state, these were dangerous things to be, even for a much-loved poet. Faiz came to my aunt’s house knowing that an angry mob was looking for him and that if they should find him things would not go well. Under the rug in the sitting-room there was a trap-door leading down into a cellar. My aunt had the rug rolled back, Faiz descended into the cellar, the trap-door closed, the rug rolled back. And when the mob came for the poet they did not find him.

Faiz was safe, although he went on provoking the authorities and the faithful with his ideas and his poems – draw a line in the sand and Faiz would feel intellectually obliged to step across it – and as a result, in the early 1950s he was obliged to spend four years in Pakistani jails, which are not the most comfortable prisons in the world. Many years later I used the memory of the incident at my aunt’s house as the inspiration for a chapter in Midnight’s Children, but it’s the real-life story of the real-life poet, or at any rate, the story in the form it reached me by the not-entirely-reliable route of family legend, that has left the deeper impression on me.

As a young boy, too young to know or love Faiz’s work, I loved the man instead: the warmth of his personality, the grave seriousness with which he paid attention to children, the twisted smile on his kindly Grandpa Munster face. It seemed to me then, and it seems to me still, that whatever endangered him, I would emphatically oppose. If the partition that created Pakistan had sent that mob to get him, then I was against it. Later, when I was old enough to approach the poems, I found confirmation there. In his poem “The Morning of Freedom”, written in those numinous midnight hours of mid-August 1947, Faiz began:

This stained light, this night-bitten dawn

This is not the dawn we yearned for.

The same poem ends with a warning and an exhortation:

The time for the liberation of heart and mind

Has not come as yet.

Continue your arduous journey.

Press on, the destination is still far away.

The last time I saw Faiz was at my sister’s wedding, and my final, gleeful memory of him is of the moment when, to the gasping horror of the more orthodox – and therefore puritanically teetotal – believers in the room, he proposed a toast to the newlyweds while raising high a cheery glass brimming with 12-year-old Scotch whisky on the rocks.

Thinking about Faiz, remembering that good-natured, but quite deliberately transgressive incident, he looks to my mind’s eye like a bridge between the literal and metaphorical worlds, or like a Virgil, showing us poor Dantes the way through Hell. It’s as important, he seems to be saying as he knocks back his blasphemous whisky, to cross metaphorical lines as well as actual ones: not to be contained or defined by anybody else’s idea of where a line should be drawn.

The crossing of borders, of language, geography and culture; the examination of the permeable frontier between the universe of things and deeds and the universe of the imagination; the lowering of the intolerable frontiers created by the world’s many different kinds of thought policemen: these matters have been at the heart of the literary project that was given to me by the circumstances of my life, rather than chosen by me for intellectual or “artistic” reasons.

Born into one language, Urdu, I’ve made my life and work in another. Anyone who has crossed a language frontier will readily understand that such a journey involves a form of shape-shifting or self-translation. The change of language changes us. All languages permit slightly varying forms of thought, imagination and play. I find my tongue doing slightly different things with Urdu than I do “with”, to borrow the title of a story by Hanif Kureishi, “your tongue down my throat”.

The greatest writer ever to make a successful journey across the language frontier, Vladimir Nabokov, enumerated, in his “Note on Translation”, the “three grades of evil [that] can be discerned in the strange world of verbal transmigration”. He was talking about the translation of books and poems, but when as a young writer I was thinking about how to “translate” the great subject of India into English, how to allow India itself to perform the act of “verbal transmigration”, the Nabokovian “grades of evil” seemed to apply.

“The first, and lesser one, comprises obvious errors due to ignorance or misguided knowledge,” Nabokov wrote. “This is mere human frailty and thus excusable.” Western works of art that dealt with India were riddled with such mistakes. To name just two: the scene in David Lean’s film of A Passage to India in which he makes Dr Aziz leap on to Fielding’s bed and cross his legs while keeping his shoes on, a solecism that would make any Indian wince; and the even more unintentionally hilarious scene in which Alec Guinness, as Godbole, sits by the edge of the sacred tank in a Hindu temple and dangles his feet in the water.

“The next step to Hell,” Nabokov says, “is taken by the translator who skips words or passages that he does not bother to understand or that might seem obscure or obscene to vaguely imagined readers.” For a long time, or so I felt, almost the whole of the multifarious Indian reality was “skipped’ in this way by writers who were uninterested in anything except western experiences of India – English girls falling for maharajas, or being assaulted, or not being assaulted, by non-maharajas, in nocturnal gardens, or mysteriously echoing caves – written up in a coolly classical western manner. But of course most experiences of India are Indian experiences of it, and if there is one thing India is not, it is cool and classical. India is hot and vulgar, I thought, and it needed a literary “translation” in keeping with its true nature.

The third and worst crime of translation, in Nabokov’s opinion, was that of the translator who sought to improve on the original, “vilely beautifying” it “in such a fashion as to conform to the notions and prejudices of a given public”. The exoticisation of India, its “vile beautification”, is what Indians have disliked most. Now, at last, this kind of fake glamourising is coming to an end, and the India of elephants, tigers, peacocks, emeralds and dancing girls is being laid to rest. A generation of gifted Indian writers in English is bringing into English their many different versions of the Indian reality, and these many versions, taken together, are beginning to add up to something that one might call the truth.

© Salman Rushdie This article is an edited extract from Step Across This Line, the 2002 Tanner Lectures on Human Values, given at Yale and included in Step Across This Line: Selected Non-Fiction 1992-2002 , by Salman Rushdie, published by Cape