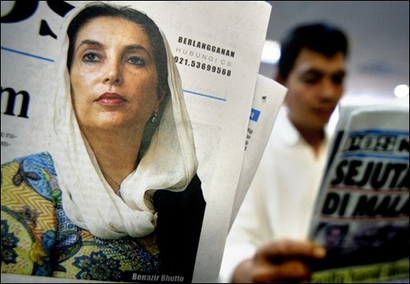

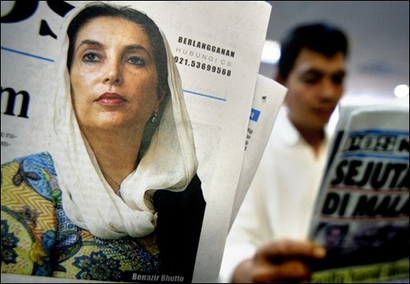

Pakistan’s flawed and feudal princess

It’s wrong for the West simply to mourn Benazir Bhutto as a martyred democrat, says this acclaimed south Asia expert. Her legacy is far murkier and more complex

William Dalrymple

Sunday December 30, 2007, The Observer

One of Benazir Bhutto’s more dubious legacies to Pakistan is the Prime Minister’s house in the middle of Islamabad. The building is a giddy, pseudo-Mexican ranch house with white walls and a red tile roof. There is nothing remotely Islamic about the building which, as my minder said when I went there to interview the then Prime Minister Bhutto, was ‘PM’s own design’. Inside, it was the same story. Crystal chandeliers dangled sometimes two or three to a room; oils of sunflowers and tumbling kittens that would have looked at home on the Hyde Park railings hung below garishly gilt cornices.

The place felt as though it might be the weekend retreat of a particularly flamboyant Latin-American industrialist, but, in fact, it could have been anywhere. Had you been shown pictures of the place on one of those TV game-shows where you are taken around a house and then have to guess who lives there, you may have awarded this hacienda to virtually anyone except, perhaps, to the Prime Minister of an impoverished Islamic republic situated next door to Iran.

Which is, of course, exactly why the West always had a soft spot for Benazir Bhutto. Her neighbouring heads of state may have been figures as unpredictable and potentially alarming as President Ahmadinejad of Iran and a clutch of opium-trading Afghan warlords, but Bhutto has always seemed reassuringly familiar to Western governments – one of us. She spoke English fluently because it was her first language. She had an English governess, went to a convent run by Irish nuns and rounded off her education with degrees from Harvard and Oxford.

‘London is like a second home for me,’ she once told me. ‘I know London well. I know where the theatres are, I know where the shops are, I know where the hairdressers are. I love to browse through Harrods and WH Smith in Sloane Square. I know all my favourite ice cream parlours. I used to particularly love going to the one at Marble Arch: Baskin Robbins. Sometimes, I used to drive all the way up from Oxford just for an ice cream and then drive back again. That was my idea of sin.’

It was difficult to imagine any of her neighbouring heads of state, even India’s earnest Sikh economist, Manmohan Singh, talking like this.

For the Americans, what Benazir Bhutto wasn’t was possibly more attractive even than what she was. She wasn’t a religious fundamentalist, she didn’t have a beard, she didn’t organise rallies where everyone shouts: ‘Death to America’ and she didn’t issue fatwas against Booker-winning authors, even though Salman Rushdie ridiculed her as the Virgin Ironpants in his novel Shame.

However, the very reasons that made the West love Benazir Bhutto are the same that gave many Pakistanis second thoughts. Her English might have been fluent, but you couldn’t say the same about her Urdu which she spoke like a well-groomed foreigner: fluently, but ungrammatically. Her Sindhi was even worse; apart from a few imperatives, she was completely at sea.

English friends who knew Benazir at Oxford remember a bubbly babe who drove to lectures in a yellow MG, wintered in Gstaad and who to used to talk of the thrill of walking through Cannes with her hunky younger brother and being ‘the centre of envy; wherever Shahnawaz went, women would be bowled over’.

This Benazir, known to her friends as Bibi or Pinky, adored royal biographies and slushy romances: in her old Karachi bedroom, I found stacks of well-thumbed Mills and Boons including An Affair to Forget, Sweet Imposter and two copies of The Butterfly and the Baron. This same Benazir also had a weakness for dodgy Seventies easy listening – ‘Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree’ was apparently at the top of her playlist. This is also the Benazir who had an enviable line in red-rimmed fashion specs and who went weak at the sight of marrons glace.

But there was something much more majestic, even imperial, about the Benazir I met when she was Prime Minister. She walked and talked in a deliberately measured and regal manner and frequently used the royal ‘we’. At my interview, she took a full three minutes to float down the 100 yards of lawns separating the Prime Minister’s house from the chairs where I had been told to wait for her. There followed an interlude when Benazir found the sun was not shining in quite the way she wanted it to. ‘The sun is in the wrong direction,’ she announced. Her hair was arranged in a sort of baroque beehive topped by a white gauze dupatta. The whole painted vision reminded me of one of those aristocratic Roman princesses in Caligula.

This Benazir was a very different figure from that remembered by her Oxford contemporaries. This one was renowned throughout Islamabad for chairing 12-hour cabinet meetings and for surviving on four hours’ sleep. This was the Benazir who continued campaigning after the suicide bomber attacked her convoy the very day of her return to Pakistan in October, and who blithely disregarded the mortal threat to her life in order to continue fighting. This other Benazir Bhutto, in other words, was fearless, sometimes heroically so, and as hard as nails.

More than anything, perhaps, Benazir was a feudal princess with the aristocratic sense of entitlement that came with owning great tracts of the country and the Western-leaning tastes that such a background tends to give. It was this that gave her the sophisticated gloss and the feudal grit that distinguished her political style. In this, she was typical of many Pakistani politicians. Real democracy has never thrived in Pakistan, in part because landowning remains the principle social base from which politicians emerge.

The educated middle class is in Pakistan still largely excluded from the political process. As a result, in many of the more backward parts of Pakistan, the feudal landowner expects his people to vote for his chosen candidate. As writer Ahmed Rashid put it: ‘In some constituencies, if the feudals put up their dog as a candidate, that dog would get elected with 99 per cent of the vote.’

Today, Benazir is being hailed as a martyr for freedom and democracy, but far from being a natural democrat, in many ways, Benazir was the person who brought Pakistan’s strange variety of democracy, really a form of ‘elective feudalism’, into disrepute and who helped fuel the current, apparently unstoppable, growth of the Islamists. For Bhutto was no Aung San Suu Kyi. During her first 20-month premiership, astonishingly, she failed to pass a single piece of major legislation. Amnesty International accused her government of having one of the world’s worst records of custodial deaths, killings and torture.

Within her party, she declared herself the lifetime president of the PPP and refused to let her brother Murtaza challenge her. When he persisted in doing so, he ended up shot dead in highly suspicious circumstances outside the family home. Murtaza’s wife Ghinwa and his daughter Fatima, as well as Benazir’s mother, all firmly believed that Benazir gave the order to have him killed.

As recently as the autumn, Benazir did and said nothing to stop President Musharraf ordering the US and UK-brokered ‘rendition’ of her rival, Nawaz Sharif, to Saudi Arabia and so remove from the election her most formidable rival. Many of her supporters regarded her deal with Musharraf as a betrayal of all her party stood for.

Behind Pakistan’s endless swings between military government and democracy lies a surprising continuity of elitist interests: to some extent, Pakistan’s industrial, military and landowning classes are all interrelated and they look after each other. They do not, however, do much to look after the poor. The government education system barely functions in Pakistan and for the poor, justice is almost impossible to come by. According to political scientist Ayesha Siddiqa: ‘Both the military and the political parties have all failed to create an environment where the poor can get what they need from the state. So the poor have begun to look to alternatives for justice. In the long term, flaws in the system will create more room for the fundamentalists.’

In the West, many right-wing commentators on the Islamic world tend to see the march of political Islam as the triumph of an anti-liberal and irrational ‘Islamo-fascism’. Yet much of the success of the Islamists in countries such as Pakistan comes from the Islamists’ ability to portray themselves as champions of social justice, fighting people such as Benazir Bhutto from the Islamic elite that rules most of the Muslim world from Karachi to Beirut, Ramallah and Cairo.

This elite the Islamists successfully depict as rich, corrupt, decadent and Westernised. Benazir had a reputation for massive corruption. During her government, the anti-corruption organisation Transparency International named Pakistan one of the three most corrupt countries in the world.

Bhutto and her husband, Asif Zardari, widely known as ‘Mr 10 Per Cent’, faced allegations of plundering the country. Charges were filed in Pakistan, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States to investigate their various bank accounts.

When I interviewed Abdul Rashid Ghazi in the Islamabad Red Mosque shortly before his death in the storming of the complex in July, he kept returning to the issue of social justice: ‘We want our rulers to be honest people,’ he said. ‘But now the rulers are living a life of luxury while thousands of innocent children have empty stomachs and can’t even get basic necessities.’ This is the reason for the rise of the Islamists in Pakistan and why so many people support them: they are the only force capable of taking on the country’s landowners and their military cousins.

This is why in all recent elections, the Islamist parties have hugely increased their share of the vote, why they now already control both the North West Frontier Province and Baluchistan and why it is they who are most likely to gain from the current crisis.

Benazir Bhutto was a courageous, secular and liberal woman. But sadness at the demise of this courageous fighter should not mask the fact that as a pro-Western feudal leader who did little for the poor, she was as much a central part of Pakistan’s problems as the solution to them.

William Dalrymple’s latest book, The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857, published by Bloomsbury, recently won the Duff Cooper Prize for History

My heart bleeds for Pakistan. It deserves better than this grotesque feudal charade

By Tariq Ali, Pakistan-born writer, broadcaster and commentator

31 December 2007, The Independent

Six hours before she was executed, Mary, Queen of Scots wrote to her brother-in-law, Henry III of France: “…As for my son, I commend him to you in so far as he deserves, for I cannot answer for him.” The year was 1587.

On 30 December 2007, a conclave of feudal potentates gathered in the home of the slain Benazir Bhutto to hear her last will and testament being read out and its contents subsequently announced to the world media. Where Mary was tentative, her modern-day equivalent left no room for doubt. She could certainly answer for her son.

A triumvirate consisting of her husband, Asif Zardari (one of the most venal and discredited politicians in the country and still facing corruption charges in three European courts) and two ciphers will run the party till Benazir’s 19-year-old son, Bilawal, comes of age. He will then become chairperson-for-life and, no doubt, pass it on to his children. The fact that this is now official does not make it any less grotesque. The Pakistan People’s Party is being treated as a family heirloom, a property to be disposed of at the will of its leader.

Nothing more, nothing less. Poor Pakistan. Poor People’s Party supporters. Both deserve better than this disgusting, medieval charade.

Benazir’s last decision was in the same autocratic mode as its predecessors, an approach that would cost her – tragically – her own life. Had she heeded the advice of some party leaders and not agreed to the Washington-brokered deal with Pervez Musharraf or, even later, decided to boycott his parliamentary election she might still have been alive. Her last gift to the country does not augur well for its future.

How can Western-backed politicians be taken seriously if they treat their party as a fiefdom and their supporters as serfs, while their courtiers abroad mouth sycophantic niceties concerning the young prince and his future.

That most of the PPP inner circle consists of spineless timeservers leading frustrated and melancholy lives is no excuse. All this could be transformed if inner-party democracy was implemented. There is a tiny layer of incorruptible and principled politicians inside the party, but they have been sidelined. Dynastic politics is a sign of weakness, not strength. Benazir was fond of comparing her family to the Kennedys, but chose to ignore that the Democratic Party, despite an addiction to big money, was not the instrument of any one family.

The issue of democracy is enormously important in a country that has been governed by the military for over half of its life. Pakistan is not a “failed state” in the sense of the Congo or Rwanda. It is a dysfunctional state and has been in this situation for almost four decades.

At the heart of this dysfunctionality is the domination by the army and each period of military rule has made things worse. It is this that has prevented political stability and the emergence of stable institutions. Here the US bears direct responsibility, since it has always regarded the military as the only institution it can do business with and, unfortunately, still does so. This is the rock that has focused choppy waters into a headlong torrent.

The military’s weaknesses are well known and have been amply documented. But the politicians are not in a position to cast stones. After all, Mr Musharraf did not pioneer the assault on the judiciary so conveniently overlooked by the US Deputy Secretary of State, John Negroponte, and the Foreign Secretary, David Miliband. The first attack on the Supreme Court was mounted by Nawaz Sharif’s goons who physically assaulted judges because they were angered by a decision that ran counter to their master’s interests when he was prime minister.

Some of us had hoped that, with her death, the People’s Party might start a new chapter. After all, one of its main leaders, Aitzaz Ahsan, president of the Bar Association, played a heroic role in the popular movement against the dismissal of the chief justice. Mr Ahsan was arrested during the emergency and kept in solitary confinement. He is still under house arrest in Lahore. Had Benazir been capable of thinking beyond family and faction she should have appointed him chairperson pending elections within the party. No such luck.

The result almost certainly will be a split in the party sooner rather than later. Mr Zardari was loathed by many activists and held responsible for his wife’s downfall. Once emotions have subsided, the horror of the succession will hit the many traditional PPP followers except for its most reactionary segment: bandwagon careerists desperate to make a fortune.

All this could have been avoided, but the deadly angel who guided her when she was alive was, alas, not too concerned with democracy. And now he is in effect leader of the party.

Meanwhile there is a country in crisis. Having succeeded in saving his own political skin by imposing a state of emergency, Mr Musharraf still lacks legitimacy. Even a rigged election is no longer possible on 8 January despite the stern admonitions of President George Bush and his unconvincing Downing Street adjutant. What is clear is that the official consensus on who killed Benazir is breaking down, except on BBC television. It has now been made public that, when Benazir asked the US for a Karzai-style phalanx of privately contracted former US Marine bodyguards, the suggestion was contemptuously rejected by the Pakistan government, which saw it as a breach of sovereignty.

Now both Hillary Clinton and Senator Joseph Biden, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, are pinning the convict’s badge on Mr Musharraf and not al-Qa’ida for the murder, a sure sign that sections of the US establishment are thinking of dumping the President.

Their problem is that, with Benazir dead, the only other alternative for them is General Ashraf Kiyani, head of the army. Nawaz Sharif is seen as a Saudi poodle and hence unreliable, though, given the US-Saudi alliance, poor Mr Sharif is puzzled as to why this should be the case. For his part, he is ready to do Washiongton’s bidding but would prefer the Saudi King rather than Mr Musharraf to be the imperial message-boy.

A solution to the crisis is available. This would require Mr Musharraf’s replacement by a less contentious figure, an all-party government of unity to prepare the basis for genuine elections within six months, and the reinstatement of the sacked Supreme Court judges to investigate Benazir’s murder without fear or favour. It would be a start.