had breakfast at Jake’s this morning and met the wonderful Ghazah Abbasi, a phd student at umass who is involved in the sanctuary campus movement. she’s also originally from pakistan and came up with this brilliant idea of organizing a pakistan conference here in the US so all of us working in activism, journalism, academia, arts and culture, etc can talk to one another. wouldn’t that be something? a great way for all of us to meet, share, be inspired and recharge 🙂

Category: self-authored

In Northampton

Started off late today and had lunch at Paul and Elizabeth’s, a well known family run eatery here in Northampton. It was a bit of a disappointment – v bland food. Or maybe I shouldn’t have ordered the sweet potato coconut soup and vegetable tempura. Later had Herrell’s handcrafted ice cream which was pretty delish. Walked around Thorne’s Marketplace for a few hours and bought tiny gifts for friends and family. But what I enjoyed most was checking out the work of local artists at R. Michelson Galleries. Bought a small triptych by Linda Wallack. Always a treat for me.

game of thrones – yawn

i came to “game of thrones” very late, as usual, but what a pile of nonsensical violence and stunningly crude misogyny. it’s supposed to be “fantasy”? indeed, it’s the fantasy of the stereotypical deeply disturbed teenage boy. i’m surprised that something this boring in its mediocrity could have ever garnered so much attention. and the misogyny? it’s so embedded in the show, so vile and routine, that it’s hard to take. digs deep into how far we’ve come as women, when this is an acceptable mainstream show in 2017. i assume it’s still going.

p.s. i know this justification well, that it’s a “period” piece. i’m sorry but it’s not a historical depiction of misogyny. look at the way it’s shot, which has nothing to do with medieval europe. they didn’t have cinematography back then. it’s the gratuitous consumption of the female body. it’s putting women in positions of subjugation where they lose all control, all identity, all the time, for no reason. it’s not about character arcs, it’s about ambient misogyny – misogyny as background noise, as backdrop to the show, much like a video game meant for teenage boys.

and the defense of the show on the basis of all the apparently strong, complex female characters and their so-called empowerment? i don’t find women acting like misogynistic men empowered and therefore don’t find the show (or alternatively the books) to be that feminist. also, i’m a bit confused about the unquestionable, historically accurate parameters within which these characters are supposed to function. as far as i know there were no dragons or zombies in medieval europe. isn’t this genre supposed to be fantasy? if we can’t fantasize about revolution, where women can be more than men in skirts, then how do we have the temerity of talking about/hoping for revolution in real life?

Islamophobia and Racism

My piece published by Indymedia, originally submitted in January 2014, revised on February 5, 2017. You can read here.

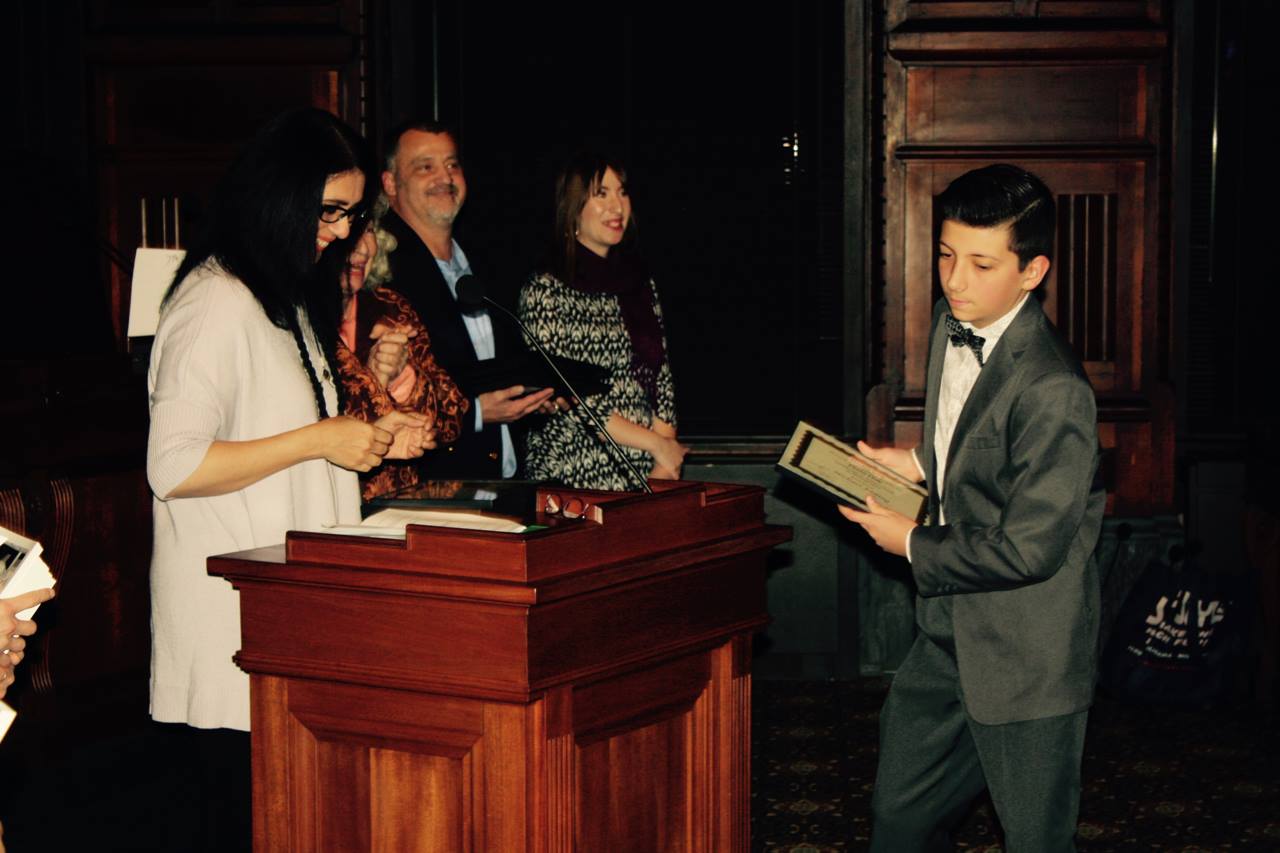

photography awards ceremony

such a joyful ceremony at rochester city hall this evening. wilson foundation academy students were presented awards for completing Flower City Arts Center’s Studio 678 photography program. an honor to participate. grateful to my husband for attending with me after a long day at work and to amanda chestnut for connecting me to this program. thank u.

A Thin Wall: Nationalism and the Partition of India

Mara Ahmed: The documentary film “A Thin Wall,” a personal take on the partition of India shot on both sides of the Pakistan-India border, took me 7 years to complete. I directed and produced another film during that time and worked on several other projects but the idea of partition stayed with me and seeped into my readings on history and contemporary politics. It became apparent to me that even though nationalism could be a used as a rallying cry for freedom and self-rule, especially in a colonial context, it could also reduce complex struggles for equity and justice to the black and white language of separation and national borders. The nation state itself, as explained by Rabindranath Tagore, is not a timeless, universal template that works for every region of the world. Rather, it is a siloed, Western approach particularly suited to capitalism and a poor fit for India. Tagore understood that military ideologies must accompany nation states and he advocated universalism rather than nationalism. From “Nationalism” by Rabindranath Tagore (1918):

India has never had a real sense of nationalism. Even though from childhood I had been taught that the idolatry of Nation is almost better than reverence for God and humanity, I believe I have outgrown that teaching, and it is my conviction that my countrymen will gain truly their India by fighting against that education which teaches them that a country is greater than the ideals of humanity.

In his essay entitled “Of Balkans and Bantustans: Ethnic Cleansing and the Crisis in National Legitimation,” Rob Nixon discusses the importance of homogeneity, the very justification for the creation and existence of nation states:

Aspirant nation-states thus find themselves in a catch-22: despite the rarity of ethnically homogeneous states, prospective states find themselves held to an archaic and potentially destabilizing vision of what constitutes a nation. Yet in seeking to reinvent themselves as singular and homogeneous, they cannot legitimately resort to the conquests and “cleansings” that countries like France, Britain, Germany, Turkey, and Spain once used to secure the internationally sanctified statehood they now enjoy.

Nixon concludes:

That canny nineteenth-century philosopher of nationalism, Ernest Renan, recognized this temptation: “Unity,” he remarked, “is always effected by means of brutality.” While this may not be wholly true of “unity,” it certainly holds for homogeneity. In the current world climate, the rewards for the pursuit of homogeneity remain explosively high. Far from resolving minority-majority tensions, the pursuit of homogeneity is liable to provoke ever smaller microethnic claims in a spiral of action and reaction, destroying in the process precious legacies of intercommunal forbearance.

Such analysis reinforced my distrust of nationalism. It helped me make sense of the road that Pakistan and India have taken post-partition. Both countries had to reimagine themselves as homogenous nations, each with a singular identity (purely Muslim or Hindu) even when this national imaginary did not square with the realities on the ground. The problematic treatment of minorities in both India and Pakistan is a by-product of building this facade of uniformity by waging war on what is religiously or ethnically incongruent.

There have always been uncomfortable links between nationalism and fascism. Under Mussolini nationalism was a way to buttress unqualified obedience to the state, while in Nazi Germany nationalism expressed itself through the narrative of a unified master race that could not afford to be “contaminated” by difference. Traditionally nationalism does not have to embody the expansionist tendencies of fascism, but military aggression can be co-opted by nationalists, especially when it’s dressed up as necessary protection for the existence and wellbeing of the state. As is obvious today, national security is invoked frequently by countries that seek to invade and occupy in order to achieve economic and geopolitical goals. This is usually done in tandem with a domestic war on religious and ethnic minorities, launched under the pretext of national stability.

Although we have come to view the nation-state as a modern phenomenon with the potential to unify nations, facilitate self-government, and organize as well as produce the betterment of communities, it is helpful to analyze the very nature of this concept in order to understand its mechanisms and the excesses that it has been, and will continue to be, susceptible to. The intimate stories recounted in “A Thin Wall” illustrate how quickly lines can be drawn across a shared territory and how nation states, once they have been delineated, only concretize that process of separation and the development of contentious national agendas.

flag lowering at wagah border

i’ve been questioning the idea of borders and nationalism for a while now, ever since i started work on my film A Thin Wall more than 9 years ago. what a treat then to witness the posturing, chanting, and use of political slogans and spectacle at the flag lowering ceremony at the wagah border, between india and pakistan. it’s interesting to look across the decorative gate (called bab-e-azadi on the pakistani side, meaning the freedom door) and see india, with a stadium full of patriotic indians cheering their border security force. the pakistanis too play patriotic songs in the interlude to the ceremony, making sure that they are loud enough to drown out indian music. the pakistani rangers are impressive – inordinately tall, lithe and elegant in how they perform a perfectly choreographed ceremony. there’s a crowd warmer who times and orchestrates all the chants and a drummer who helps the audience keep its rhythm. quite an experience.

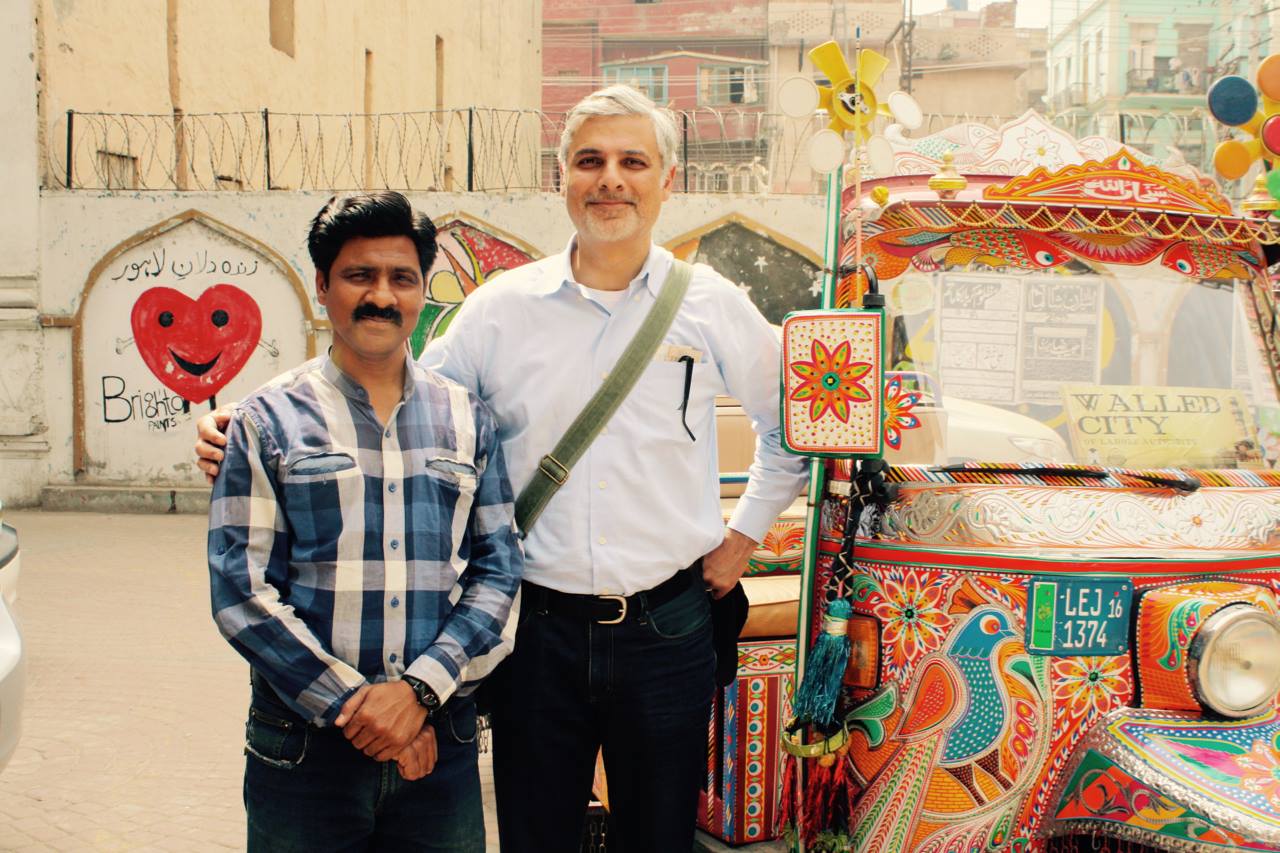

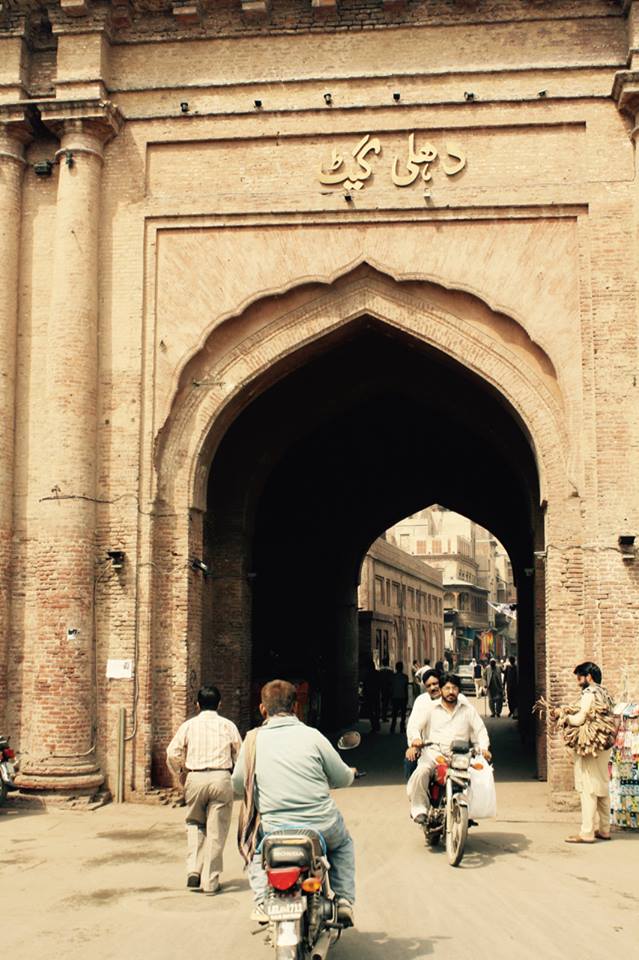

lahore’s walled city

we took the rangeela rickshaw tour yesterday to explore lahore’s old walled city. the northwestern part of lahore was fortified by a hefty wall during mughal rule. there used to be 13 gates into the city – only 6 survive. the rest were demolished by the british in order to defortify lahore after the war of independence (which they still like to call a “mutiny”) in 1857.

old lahore breathes history. i’ve always loved everything about it – its narrow circuitous streets, spice markets, busy bazaars, ancient havelis with bamboo chick blinds and balconies carved with intricate, lacelike woodwork, its fruit vendors and ornate mosques, and the continued vigor of its people (many families have lived here for centuries). i was happy to learn that proper sewerage systems have been installed in many parts of the inner city and that power lines have gone underground. hope that important work continues.

i had already visited the wazir khan mosque, more than a decade ago. its vibrant images appear regularly in my work. built in the 17th century to enclose the tomb of sufi saint miran badshah, the mosque used to be part of a larger complex with stalls for calligraphers and bookbinders. it is embellished with stunning frescoes and tiles and elaborate persian motifs, such as cypress trees and star shaped flowers. architectural ornamented vaulting inspired by the alhambra (islamic spain) can also be found in the mosque. a true feast for the eyes.

what i enjoyed most on this guided tour were the shahi hammam (royal bathhouse) excavation of which has been completed recently and the life story of our guide.

right inside of delhi gate (one of the gates into lahore’s walled city, it used to open onto the only road that went from lahore to delhi – appropriately enough, there is a lahori gate in the old city of delhi), is the shahi hammam. built in 1635 by the then governor of lahore. in line with persian design, the bathhouse boasts plenty of natural sunlight via skylights placed in the center of dazzling high ceilings, heated floors, excellent ventilation, a dressing area, warm baths, and a sauna. pictures show what the baths must have looked like back in the day. stunning.

finally, i was extremely moved by the story of our guide, muhammad javed, who grew up in the walled city. he was born into a family of musicians and told us how he hated the word mirasi (genealogists and traditional singers and dancers in india and pakistan). it is a word that comes with a lot of caste baggage and is used as a pejorative in this part of the world. javed rebelled against this vile casteism and resisted becoming a tabla player in spite of the pressure from his father. he sold snacks, boiled eggs, newspapers, barbecued meat at various times in his life, but continued to go to school. he supplemented his income by tutoring other students and was able to graduate. he loves the history of inner city lahore and so became involved in tourism. he is now in the final stages of writing a book and his tours are requested by visiting heads of state. he has 4 kids and on top of teaching them urdu and english, he is also teaching them german, chinese and italian. he wants them to be active citizens of the world.

this is the kind of chutzpah and ambition that i love in the people of pakistan. our driver, who has been kindly taking us around the city, is the same. he lives alone in lahore and visits his family in gujranwala once or twice a month. whatever he makes he sends home. he and his wife are completely invested in the education of their two kids. they don’t just depend on schools. for example, they also teach their kids iqbal’s revolutionary poetry. how cool is that?

Jahangir’s Tomb and Badshahi Mosque

We spent yesterday visiting Jahangir’s Tomb and the Badshahi Mosque. Both are made of Lahore’s distinctive red sandstone, imposing in their scale, and harmonious in how they combine restraint with rhapsody. Jahangir, son of Akbar, was the fourth Mughal emperor to rule over the subcontinent. The construction of the mausoleum where he was eventually buried is mostly attributed to his son Shah Jahan, but many say it was, in fact, the vision of his wife Nur Jahan. It took 10 years to build, from 1627 to 1637. The exterior of the mausoleum is simple but its interior is alive with gorgeous frescoes, tile mosaic and marble work.

The tomb’s white, inlaid marble is exquisite. There is something sacred about the incredible amount of work it took to carve out and embed each petal and leaf with just the right shade or pattern of veined precious stone in order to create the most delicate, flowering arabesques. Heart-achingly beautiful calligraphy takes the form of black-marble inlay and expresses the ninety-nine names of Allah, in line with Islamic mystic traditions. A stunning visual poem, if ever there was one.

The Badshahi Mosque was built by Emperor Aurangzeb (1671-1673). It remained the largest mosque in the world for more than 300 years. Here too we find balance and symmetry, a rootedness that is expansive and serene. But again, there is the counterpoint of passageway opening onto passageway for what seems like eternity, of arches and windows affording us a million different angles, perspectives and points of view, of reflections on polished marble floors that continue to mirror reality forever. Not so simple and straightforward after all.

Lunch at Cuckoo’s Den in what used to be Lahore’s red light area.

breakfast at punjab club

delightful breakfast on our veranda this morning, with the sun warming us up ever so gently, a cacophony of local birdsong, the muffled sounds of early morning busyness gliding over a spill of plant and flower and kinnow tree, and our own chai walla 🙂

Organizing the reading of Jen Marlowe’s play

Excellent meeting with Reuben J. Tapp this morning. Found out that he’s involved with the African American theater companies that form The Rochester Bronze Collective and perform at MuCCC. Even more thrilled at the prospect of working with him on a play by Jen Marlowe. Thx for this brilliant connection Scott Lancer. And yes, 490 is driveable, although it’s better to stay slow. Apparently up to 42 inches of snow from this latest storm, in some areas of upstate NY. Stay warm everyone!

feminism and intersectionality: my talk at SJFC

wonderful discussion about feminism and intersectionality at St. John Fisher College this morning. such a pleasure to talk about the work of lila abu lughod, saba mahmoud, houria boutelja, audre lorde, nadine naber and anu ramdas.

excellent questions from students – one about the contradiction between the west’s concern for women’s rights in muslim-majority countries and their sabotage/disruption of political movements for democracy and self-determination.

nadine naber has written extensively about the egyptian revolution – how women were “active participants in a grassroots people-based struggle against poverty and state corruption, rigged elections, repression, torture, and police brutality,” yet much of US public discourse framed the revolution through “islamophobia logics” and was driven by the question: what if islamic fundamentalists take over egypt? she locates this discourse “in the historical trajectory of the post-cold war era in which particular strands of US liberal feminism and US imperialism have worked in tandem. both rely upon a humanitarian logic that justifies military intervention, occupation, and bloodshed as strategies for promoting democracy and women’s rights. this humanitarian logic disavows US-state violence against people of the arab and muslim regions rendering it acceptable and even, liberatory, particularly for women.”

another question was about the need for muslims to condemn every act of terrorism when no such demand is made of the white christian majority. of course, we talked about mahmood mamdani’s “good muslim, bad muslim: america, the cold war and the roots of terror.”

we explored postcolonial feminism and muslim feminism and discussed saba mahmood’s work on the piety/mosque movement in many muslim-majority countries of the world.

finally, we examined the politics of “non mixite.” houria boutelja explains how colonialism and racism have already divided muslim men and women and therefore the idea of building feminine power by excluding muslim men might not be effective in this context. audre lorde too talks about racist oppression being shared by black women and men, because of which they develop joint defences and joint vulnerabilities. similarly, anu ramdas has written about how “the reformative agenda of taming dalit masculinity ignores the reality of inter-operating oppressive cultures in a caste society.”

so satisfying for me to mention these incredible women and analyze their incredible work, on this cold snowy morning, all thx to Roja Singh, who organized this event and drove me back and forth in this bad weather. a true sister in the stuggle for justice and equality. what feminism should be all about!

international women’s day

yesterday, on international women’s day, i spoke at the pittsford rotary about my work and started by explaining the history and importance of women’s day. wasn’t sure how a group of white businessmen in suits was going to respond to my presentation but they were not afraid to engage and asked excellent questions. the talk was organized by my dear friend, and person-2-person partner, jeanne strazzabosco. later i met with two close friends, judy toyer (an attorney who grew up in alabama during jim crow and is committed to anti-racism work) and sarita arden (an artist who came to social justice very early on as a school girl), to talk about revolution. and of course, we all wore red.

lovely weekend

wonderful weekend. trip to ithaca on saturday morning to visit our son and have lunch with him, then off to the little theatre to see “i am not your negro,” followed by ethiopian food at zemeta with a couple we love. on sunday, dinner at our iraqi american friends’ house – delicious home cooked iraqi food, comforting tea in beautiful teacups and then a game of table tennis to wrap things up. couldn’t have cared less about the glacial weather.

my review: i am not your negro

finally saw “i am not your negro” (had been waiting patiently for the film since i came across an interview with raoul peck back in 2016), and am still shaken. it’s an emotional experience. yes, the utter brutality of white supremacy, yes, baldwin’s luminosity and fearless words, yes, peck’s genius in reincarnating baldwin and making him present thru the medium of film, yes, samuel l jackson’s stunning narration (it doesn’t mimic baldwin’s unique cadence but rather remodulates jackson’s voice to produce a slower, smoother, weightier rhythm and timbre and flows seamlessly in and out of baldwin clips), yes, the bold graphics and robust music that highlight baldwin’s vigor and audacity but also his pain, yes, the surreal reliving of the murders of medgar evers, malcolm x and martin luther king (none of them lived to be 40), yes, the vulgarity of doris day and gary cooper dancing heedlessly when juxtaposed with photographs of lynched bodies, yes, the ugliness exposed by the desegregation of schools and captured in photographs and video footage, yes, baldwin’s searing commentary on white america’s immaturity and preference for a world of warped fantasy (embodied by john wayne, who spent his entire film career admonishing and shooting native americans), yes, to all of this and more. but what broke my heart irrevocably was when, toward the end of the film, the camera zooms in on the faces of black men and women. we are able to make eye contact with them directly, personally, and it’s almost unbearable to look them in the face. the film’s eloquence and power are worthy of james baldwin. and that’s saying a lot.