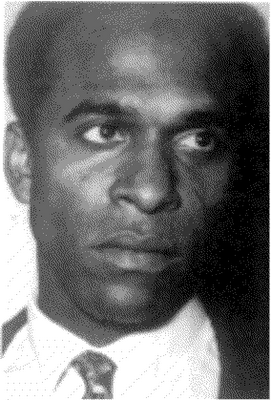

Interview with Tariq Ali

by Talat Ahmed, Socialist Review, November 2006

‘The history of the development of Islamic civilisation is one of adaption and intermingling. It is one of both influencing the non-Islamic world and being influenced by it.’ Tariq Ali challenges the myth that Islam is incompatible with the West in his four novels about the Muslim world and Europe. He discussed them with Talat Ahmed.

Since Jack Straw made his comments on the veil, politicians have been falling over themselves to demonise Muslims in Britain. Now university lecturers are expected to spy on “Asian-looking” students in order to spot potential terrorists, while parents are warned to be on the look out for “fundamentalist” tendencies among their children. Britain seems to be in the grip of an anti-Muslim hysteria that has been gathering pace for some time. Tariq Ali’s four novels on Islam and its relationship to Europe provide not only welcome relief but also an antidote.

“The politicians and media have created a dominant image of Islam that is one of bearded terrorists,” says Tariq. “Almost everywhere these days you can read nutty right wing novelists like Martin Amis talking about Islam as an ‘evil religion’. To fight against that is an uphill struggle.”

The attacks on Muslims perpetuate the myth that Islamic culture is backward and its politics despotic. This view is even shared by many liberals, and some on the left, who use the language of “Islamic fascism” and see Islam as a religion characterised by intolerance. For them, it is a creed that must reform or perish. Among those from a Muslim background there are two main responses – either an attempt to deny their Islamic heritage in an ever more desperate attempt to avoid racial stereotyping and abuse, or a closer identification with some aspect of Islamic culture. Both responses tend to perpetuate a version of Islam that is uniform, set within definite parameters and closed to any alternative forms of interpretation.

Tariq’s novels lay down a challenge to these notions. The first four novels from the Islam quintet are set in Europe and cover Islamic civilisations in different periods of European history. As you read Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree, The Book of Saladin, The Stone Woman and A Sultan in Palermo the most striking feature is a world of plurality, cosmopolitanism, tolerance and the quest for knowledge.

When I asked Tariq why he decided to write novels based on the contact between Christianity and the Islamic civilisation in Europe, his response was telling. “In 1991 during the first Gulf War, I heard some professor on TV say something that is now so common that nobody talks about it. He said, ‘The Arabs are a people without political culture.’ This really angered me as I knew instinctively that this was not true.

Secondly, it raised in my own mind the question as to why, of all the three big universal religions – Christianity, Judaism and Islam – only Islam had not had anything which we could say is the equivalent of the Reformation that broke the power of the Catholic hierarchy that dominated Europe until the 16th century. It is well known that I am not a religious person, I grew up and remain an atheist, but this question revived my interest in Islamic culture and Islamic history. I wanted an answer to this question and I thought the answer lay in Europe and not in the Arab world.”

Tariq’s quest took him to Spain, to the great Islamic monuments of the Alhambra in Granada, and the palaces and forts of Muslim kings in Seville and Cordoba. He went to Sicily to see the city of Palermo, which used to be described by travellers as the city of a hundred mosques, but today has none. “Then I began to read and to think,” he says. “I thought that the best way to recover that lost world was to depict its last years, its decline and fall. I could have just written an essay but I felt after seeing those monuments, that I wanted to bring back the people who had lived around there. At that time the story of Islam in southern Europe was not very well known. In school history books it appears as just a paragraph – the Muslims came to Spain; the Catholics threw them out. That’s it.”

“Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree is set in Moorish Spain in the period after the city of Granada was ‘reconquered’ from Muslim control – a time of Catholic restoration, when Jews and Muslims were expelled from the country,” Tariq explains. The story begins with the infamous “bonfire of the books” in Granada, when, under the orders of Archbishop Ximenes de Cisneros, whole collections of books on mathematics, science, astronomy, philosophy, medicine, and handcrafted copies of the Koran were burnt. The novel manages to symbolise both the unique contribution of Arab culture and learning to Europe as well as the destruction of that learning at the hands of “civilised” Christendom. “The book has been well received in Spain, not only by literary agents and publishers, but also by migrant Arab workers who thanked me for telling the story,” says Tariq.

Christian Crusades

The second novel, The Book of Saladin, is situated in the reign of the Kurdish leader Saladin at the end of the 12th century. Saladin was the sultan of Egypt and Syria who succeeded in uniting the Arabs against the marauding Christian Crusades. The story of Saladin is narrated by his court – appointed scribe, Ibn Yacub, who is Jewish. “The decision to make the chronicler a Jewish character was significant as it raised a few eyebrows when it was published in the Arab world,” remembers Tariq.

But his reasoning is simple. “The Jewish narrator reflects the history of that time,” he says. “There were large numbers of Jews in all the Arab courts and according to one study 70 percent of Saladin’s advisers were Jewish. His own personal physician was a Jew. One reason for reviving this history is to show that there wasn’t any basic hostility between Islam and Judaism at that time. The hostility only started in the 19th century with the influx of Jewish settlers into Palestine.” Tariq points out that when Saladin took Jerusalem from the crusaders, he issued a proclamation stipulating that the city had to remain open to people of all faiths, and state subsidies were provided to rebuild synagogues. The Book of Saladin is the only novel by Tariq that has been translated into Hebrew and published in Israel.

“Both Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree and The Book of Saladin depict a society that was characterised by cultural diversity, an intermingling of religious and cultural practices that were torn asunder by the impact of an intolerant western creed,” explains Tariq. “This does not mean that these societies were tension free or harmonious. In both the Arab world and Islamic Spain there were clashes between different social groups, but they were not on the systematic scale that some commentators believe.”

Tariq’s third novel, The Stone Woman, is set at the end of the 19th century during the twilight of the Ottoman Empire. This shifts the focus to a very different era – one of decay and decadence, one of corrupt officials and courts. The family of Iskandar Pasha are holidaying on the Mediterranean island of Marmara, and here loves, petty intrigues and personal jealousies are set against the backdrop of the political and social indifference of the ruling dynasty. “My novel is set in one location and from here you see the degeneration of this old ruling class Ottoman family. In many ways it mirrors the disintegration of their empire,” says Tariq.

The reconquering of Spain by the Catholic church forced thousands of Muslims to convert to Christianity, and those who attempted to revert to Islam were threatened with death. A popular sentiment among Muslims in Spain was that the navies of the Ottoman Empire would come to their rescue, but no fleet ever set sail. Tariq has no difficulty explaining why the longest lasting and largest Muslim empire the world had seen did not seek to assist other Islamic civilisations elsewhere in the world. “The Ottoman Empire acted the way all empires do, in its own interests. It was not going to be generous; it did not have any plans to save world Islam,” he says.

The Ottoman Empire also failed to adequately respond to the development of the new economic system that would come to dominate the world. “The period of the Ottoman Empire coincided with the growth of capitalism in western Europe,” says Tariq, “but the Ottomans were completely sealed off from it.” The demise of the empire can be attributed to the social and economic structure of the state, which, according to Tariq, “was totally centralised. None of the regions or cities was allowed the autonomy necessary for capitalism to grow and function.

“Merchant trade was highly developed but the transition from merchant trade to capitalism proper never took place in Ottoman lands because of the ways social, economic, cultural, political and religious power were concentrated in the hands of one family.” The creation of such highly centralised state structures resulted in economic priorities being determined by a very small elite who were not in a position to expand production. This caused the Ottoman Empire to stagnate and then crumble.

Directing events

In all four of the novels, women are portrayed as strong-willed and very determined individuals who make demands on their men folk and children. It is particularly true of the fourth book, Sultan of Palermo, which looks at the life of Muhammad Al-Idrissi in the 12th century. He is the court cartographer – a geographer and a man of medicine and learning. This is a world of science, philosophy and rational thought.

The jealousies surrounding him emanate from the social and political prestige that Al-Idrissi enjoys as a Muslim in a Christian court where envious Catholic priests, who are mistrustful of Muslims, fear for their own positions within the court. Here women play a significant role, directing events through the men that they control, while pursuing their own interests with a single minded resilience.

“What has been written about the periods that my novels are set in indicates that women in Islamic societies were powerful individuals, even when they were being prevented from governing the state,” says Tariq. “We know that in both the Abbasassides caliphate in Baghdad, and the Moghul Empire in India there existed many extremely powerful queens and princesses. In the Ottoman Empire women often ruled from behind the scenes. So in the novels I wanted to break this racist myth of Muslim women exclusively as victims.”

The women of the ruling class were not just passive victims of the harem, but also active instigators of sexual encounters. Nevertheless the novels do not present these societies as enlightened to the point where women are liberated. Tariq is clear that in all medieval societies, whether Christian, Jewish or Islamic, women were treated as second class citizens with very few rights.

The Stone Woman takes up the question of whether Islam is a particularly dogmatic religion by looking at the question of idolatry. The stone woman of the title refers to a statue that the Pasha family go to, not to worship but to speak to as a “silent psychiatrist” that they can confess their sins to. “You cannot tell the truth to each other as it is too scandalous,” explains Tariq, “so you speak to the statue as it cannot respond.”

He makes the point that Islam, like Judaism, forbids the worship of graven images, but this is not the same as forbidding the depiction of the prophet Mohammed. “In the 13th, 14th and 15th century there were Muslim painters in Herat in Afghanistan, in Persia and in parts of Turkey who painted the prophet. So the notion that this is outside the Islamic tradition is absolute rubbish, which is why I was very angry with the way that some people responded to the Danish newspaper cartoons that attacked Islam. The cartoons were racist – and should have been attacked on that basis. They should not have been attacked on the basis of an Islamic theology which outlaws depiction of Mohammed. That is nonsense.”

“The history of Islam is a history of breaking with past traditions,” insists Tariq, “including the Christian idolatry of the Madonna, and Jesus as the son of god. Mohammed realised very early on that Islam had to build against this whole current,” he says. “So Mohammed built it as something in which you have a complete break with anything that entails a worship of any graven images, and of course that included the worship of himself. A central fact of the Islamic religion is that the prophet emphasised that he was a human being, not a divinity – he was a messenger of god who had heard god’s message. It was not Mohammed’s message.”

“The history of the development of Islamic civilisation is one of adaptation and intermingling. It is one of both influencing the non-Islamic world and being influenced by it. This is a history that has not only been hidden and denied in Europe, but one many radical Islamists are ignorant of. Though they may use the language of liberation and fighting the ‘Satan’ of imperialism, on religious questions the Islamists also attempt to present a timeless, monolithic and homogenised set of doctrinaire beliefs that bear little resemblance to how the religion developed.”

Tariq argues that the early medieval world of Europe, when Islam dominated much of the Mediterranean, was the highest point of Islamic cultural development. And without contact to the Islamic world, Europe could not have developed the way it did.

“Learning came with Islamic civilisation. This was the civilisation that became a conduit, a bridge between the ancient world and today’s world. In Toledo the Spanish Muslims set up a school of language that translated all the main texts from ancient Greek and Latin into Arabic, thus making them available in Europe. When you read the 12th century Spanish Muslim, Ibn Rushd, on Aristotle you find that his writings are a great work of political theory in their own right. No one disputes the fact that it was Islamic and Arabic learning in mathematics, astronomy and medicine that developed these disciplines. This should be taught as history in school – it’s a much better way of countering anti-Islamic racism than single-faith schools.”

Tariq’s novels are an enjoyable history lesson as well as a challenge to the wave of bigotry that surrounds us at present but, more than that, they are great stories which are beautifully told. The final novel in the quintet will be set in the modern world post-9/11. It will take up the question of why it is that at the dawn of the 21st century religion is still able dominate people’s lives, and why millions of individuals are drawn to it. One theme that Tariq wants to tackle is the failure of secular nationalism in the Arab world to offer solutions to problems of poverty, underdevelopment and Western military and economic power. On the basis of the first four, we eagerly await this final chapter.